On the morning of April 25, 1974, as I sat in a 5th grade classroom in Caldas da Rainha, Portugal, my teacher's nervous look out the window drew my attention to a long chain of military vehicles on a nearby road. Our provincial town had a large military base, so I made nothing of it. But within a few hours my country and people's forbidden secret would be revealed to hundreds of thousands of children like me: we had been living under something called "a fascist dictatorship," for nearly 50 years.

A bloodless military coup put an end to it that day with what came to be known as the Carnation Revolution of April 25. The circular military parade around the city's square -- "Praca da Fruta" -- that afternoon, the cheers and cries of the people, the carnations tossed high in the air and adorning gun barrels remain vivid memories -- and I have relived them often since the unfolding of the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia.

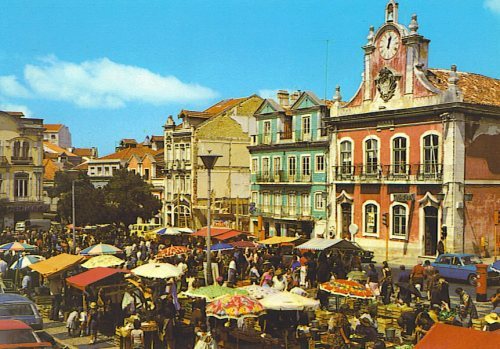

An image of "Praca da Fruta" (Fruit Square) in the 1970's, shared by a blogger who recalls his adolescence in Caldas during that period. The square gets its name from the daily farmers' market.

An image of "Praca da Fruta" (Fruit Square) in the 1970's, shared by a blogger who recalls his adolescence in Caldas during that period. The square gets its name from the daily farmers' market.

The weeks and months that followed were filled with hope and excitement: the political police was dismantled and prisoners freed; ex-patriots and exiled party leaders returned home; political parties organized for free elections; colonies prepared to be handed back to the African people -- and young and old sang along to proud revolution songs. But social and political upheaval would ensue, and so would violence and domestic terrorism. At the age of 12, living in Lisbon, I joined a demonstration of the social democratic party at Commerce Square -- Praça do Comércio -- and had my first taste of tear gas, allegedly thrown by a rogue left-wing faction. Separated from my slightly-older friends in the chaos that followed, I ran home alone, for miles, to my unsuspecting parents -- one precocious and unusual "coming of age" event!

Portugal's economic situation would worsen for years to come, and I can't think of anyone in my circles whose economic status improved as a result of April 25. The glory of the revolution was about having a voice. All through my teens, living in Portugal's capital, I would sit at cafés after school to discuss politics, ideology, philosophy -- the past and future of the country. That kind of personal and political awakening was "the change." Throughout my adult life in the United States, I have often been labeled "opinionated" (mostly by men), and "challenging" (mostly by women). You bet! When you wake up one morning to realize your parents and grandparents lived the whole of their lives without a voice, how can you ever let go? For one, unlike too many of my American acquaintances, I could never pass on my right to vote.

In early 2011 when the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions were all the news, my love for writing notwithstanding, the idea of blogging was the furthest from my mind. In fact, I was social-media-free and proud of it. While the role of social media in the mobilization of the Arab uprisings was ultimately overplayed by Western media, daily observations at the time -- and later research -- would suggest a correlation between events in the Middle East, the participatory news-culture of social media, and a change in Americans interest for international news and affairs.

That research caused me to look at social media in a different light, and I became particularly curious about the role of bloggers. When my graduate program at Pace University offered a blogging course last fall, I signed up. Assigned reading for "Blogging a Better Planet" -- taught by Andrew Revkin, The New York Times' journalist and blogger of DotEarth -- brought me to Scott Rosenberg's book, Say Everything: How Blogging Began, What's Becoming, And Why It Matters. An excerpt:

"Whatever the drawbacks and limitations of blogging, it serves, today, as our culture's indispensable public square. Rather than one tidy 'unifying narrative,' it provides a noisy arena, open to everyone, for the collective working out of old conflicts and new ideas."

I was sold! It was about having a voice -- a revolution of sorts. Amador Square, the name of my personal blog, came clearly to me, inspired by the idea of citizen or amateur journalism ("amador" is Portuguese for amateur), and the concept of the "public square": the public square of ideas, and the physical public squares around the world, where Tharir-inspired protests took place in 2011. Later on, my Media and Communication Arts program at Pace offered me the opportunity to replace the traditional graduate thesis with a blogged thesis project. I had remained interested in the evolution of the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions, thus the research questions presented themselves: in the aftermath of elections in Tunisia and Egypt, how would the young, well-educated activists who ushered in the regime-change find themselves and their aspirations represented? Would the many activists before them -- labor unions, women -- who led critical pre-revolution movements, be pushed aside by more powerful constituencies?

My tentative hypothesis contends that, even in a predominantly religious and conservative Arab world, the under-30, most populous generation of Arabs is determined to sustain a strong trend toward more civilian participation and representative government. It's a genie-out-of-the-bottle predicament. They will continue to use every mean at their disposal -- from the public square to social media, and greater political organization -- to insist their new-found voices be heard, beyond elections, a new constitution, and possible economic progress.

In addition to the obvious language barrier, the greatest challenges the project has presented thus far have to do with representing the many dissonant voices of the revolutions -- from extremely religious and conservative, to extremely liberal and Westernized. That inscrutable complexity is further complicated and muddled by Western interpretations, expectations -- and interests.

Do Arabs want what we, Westerners, think they want? Speaking to NPR on the one-year anniversary of the Tunisian revolution, Shadi Hamid, director of research for the Brookings Doha Center, noted that "the Arab world is a religiously conservative place and people generally want to see Islam playing an important role in public life." And, he added, "America has to learn to live with political Islam." But what will political Islam look like? How will the new Middle East -- and the political awakening and activism it has inspired around the globe -- impact us all?