By Steven Kelly, University of Wisconsin. Contributor at the International Political Economy Hub blog.

Eight years after the global financial crisis, the world economy as a whole looks mediocre, and Europe's looks bleak at best. As central bankers across the world have executed formerly-unconventional monetary policy maneuvers in efforts to revive output and price growth, they have become increasingly frustrated with the lack of assistance from fiscal policymakers. This failure to support monetary policy is especially potent in Europe where creditor nations and the European Commission have demanded European countries reduce their debt loads and budget deficits--even those with the capacity to borrow and the need to spend. The political dominance of Europe's creditor nations, most notably Germany, has thus left the European recovery effort with a deflationary bias and a poor outlook.

Even the European Central Bank (ECB)--which, since the crisis, has been viewed as an institution that kowtows to the politics of Europe's creditor nations--recently released a study demonstrating the positive economic effects to the eurozone as a whole if Germany were to engage in debt-financed spending. Instead, internal politics have left Germany obsessed with running a budget surplus and reducing its already relatively-low debt load. While this debate over the need for fiscal assistance versus fiscal consolidation has roiled European politics, especially between creditor and debtor nations, no one has stopped to realize that this tradeoff is a false dichotomy.

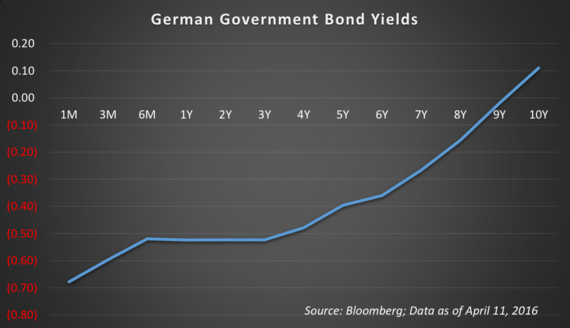

German government borrowing rates are negative beyond nine years out (see figure) as German debt is viewed as one of the few safe assets left in Europe. Negative interest rates imply investors are willing to pay Germany for the privilege of holding the safety of its bonds. Thus, even if, for political reasons, Germany doesn't want to increase government spending, it should be borrowing as much as it can and stuffing the cash under its proverbial mattress. Borrowing at negative rates means Germany could simply set aside the amount needed to make the future interest and principal payments and put the money earned from the negative yield toward the budget. Surely the European Commission would approve of such an operation given that the additional borrowing would actually improve Germany's budget dynamics (and given that Germany is the Commission's most important proponent of its strict fiscal rules).

Even if Germany didn't spend a euro, the ECB would be grateful in at least two ways. First, the credibility of the ECB's quantitative easing (QE) program has been called into question due to the fact that current rules for the program stipulate that the ECB must conduct its government bond purchases in proportion to eurozone members' relative economic size--meaning, if investors won't sell their limited supply of German bonds, the ECB wouldn't be allowed to continue purchasing other governments' debt. A boost in debt issuance from Germany would increase certainty surrounding the ability of the ECB to continue its QE efforts as needed and thus continue purchasing bonds from other nations as well--many of which desperately need it. Secondly, by increasing the supply of safe German government debt, the market-clearing interest rate on safe assets will be higher and could even push yields positive (and, in the process, also satisfy Germany's finance minister's public call for higher interest rates for the sake of German savers). By raising the market-clearing safe asset yield, the ECB's set of policy interest rates--which are trapped at their lower bound--would become more stimulative and thus boost economic activity. This would be a win for the eurozone economy, the ECB, and German politicians. Who knew that was possible? And who would've thought Germany, of all nations, would be refusing free money?