The aesthetics of cinema's bildungsroman.

By Shari Kizirian

Mystery. Angst. Wonder. And the occasional burst of joy. It's what filmmakers seem to focus on in their portrayals of childhood. Think feathers floating down around the boys in Zero de conduit's giddy pillow fight; Antoine's wild panting run from reform school to the seashore at the end of 400 Blows; Little Ana's momentary encounters with her dead mother in Cria Cuervos; Holy Girl's enigmatic best friends coiled in a touchless embrace; the exuberant stretching of the aspect ratio in Mommy. Movies centered around children, and how they grow up, tend toward ethereal aesthetics, streaming light, soft focus and silence, close hand-held camera impressions, or from the far distance, just clear of earshot, perhaps mimicking the inchoate, illiterate nature of childhood memories. Testing the definitive outlines of storytelling while exploiting the spectral potential of cinema, a few recent movies about childhood achieve an illuminating balance.

What Maisie Knew

The barely school-aged Maisie is a pawn in her parent's contentious split. The camera captures her through a dreamy scrim as snippets of fights drift in. Maisie seems content to occupy her own delimited world, approaching with a Zen-like serenity just about any change in her circumstance, accustomed to playing alone, waiting forever on school grounds, sitting in towering foyers with only the doorman for company until the end when she exerts a very grownup will and gives the audience a rare jolt of child-like joy.

Blame It on Fidel

When the bearded and braless suddenly invade her bourgeois sphere, the nine-year-old Anna becomes the family's sole paragon of propriety, deploying epic pouts and stern glares to demand a return to the status-quo. Meanwhile her giggly younger brother adapts to the new regime of looser bedtimes, refugee nannies, public schools and midnight manifesto-writers almost instantly. Stationed at her prim altitude, the camera allows access to only what Anna is directly told or picks up through the walls or cracks in doorways. Like any good conservative Anna changes slowly. When she eventually accepts the new reality, she can finally relax and act her own age.

The Kid with a Bike

Cyril is followed very closely during his testosterone-spiked rages and through his fevered peddling to find his estranged father in the Dardenne brothers searching hand-held style. Doubt and angst are the prepubescent boy's most prominent emotions as he seeks stability in what must feel like a wisdom-free zone. Somehow, like Maisie, he manages to choose a caretaker, more on instinct than on any visible evidence. The proof of his blind faith comes only in time.

Tomboy

Soft-focus shots of sun-dappled treetops open this story of a prepubescent girl trying to pass as a boy. The film's initial journey is an opportunity and she grabs it, introducing herself as Mickäel to the kids in her new neighborhood. She takes imprudent chances, taking off her shirt during a rough soccer match, getting into knock-down fights, inserting a length of Play-doh in her improvised Speedo. The film is sweet and melancholy and the images of Mickäel, mostly isolated, reinforce the loneliness of her identity crisis but also the deep reserves of her determination to pass.

Lore

Shot through with fairy tale aesthetics, Lore includes the nightmarish along with the magical. At first seeing the world through the distortions of the beveled windows of her home befitting the privileges of high rank, the fourteen-year-old Hannelore soon confronts an unmediated reality as she is suddenly responsible for the survival of her four younger siblings and must drag them through the manmade detritus of war after her Nazi-devoted parents are imprisoned by the Allied forces. The shaky, shallow-focus photography enforces the urgency of their immediate needs (and the amorality of how they are met), but also the fragility of children who have the protective shields snatched down from around them.

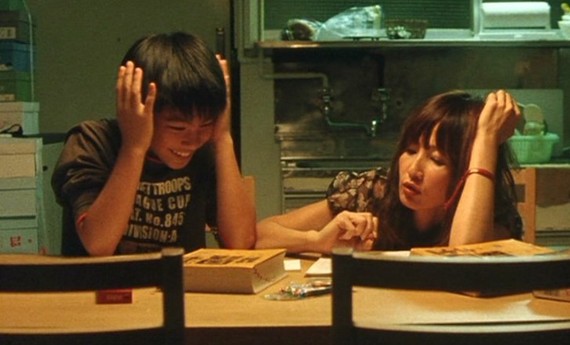

Nobody Knows

More willing than Hannelore, Akira cares for his younger siblings' every need. Fearing social services would split the four of them up, he feeds them, pays the bills, and brings them the occasional treat, exhibiting an uncanny maturity by giving them gifts in the name of their absent mother. Director Hirokazu Koreeda hones in on the details, little hands, candy boxes, piles of dirty dishes, a stain, dwindling wads of cash, a drop of blood, a worn red suitcase, capturing everything in a washed-out color palette. Even when Akira cannot prevent the inevitable worst, he keeps the family together and in a long wordless sequence finds a way to imbue tragedy with meaning.

The Return

Two brothers come home one day to find their totalitarian father, who was inexplicably gone, now inexplicably back. The young Vanya bristles under this stiff new bridle, the older Andrey acquiesces, as they are enlisted for all manner of arduous tasks. They go on a fishing trip and instead of familial bonding there's more random disciplining and, now, the caprice of the natural world to face. Andrei Zvyagintsev's remarkable debut can be read as a submission-to-a-higher-will parable: defiance, conformity, authority entwined in an eternal struggle. Shot in the atmospheric hues of perpetually predawn light, the film communicates, using what Dave Kehr calls both "highly naturalistic and dreamily abstract visuals," the pain of our arbitrary existence.

I Killed My Mother

In his first feature, actor-director Xavier Dolan employs the wide-screen frame to create distance between him and his kitschy mother (the chameleon Anne Dorval) and closeness to cultured schoolteacher (the endearing Suzanne Clément) who befriends him. Hilarious color-saturated tableaux and slow-motion cathartic fantasy segments cut quickly back into a neutral reality. His mother blames their deteriorating relationship on typical teenage rebellion, which manifests as cursed-laden apoplectic outbursts--until she has one herself. Dolan explores another mother-son relationship in last year's high-spirited Mommy, for which the young director takes even bolder formal risks with the surety of a veteran filmmaker.