If a century of movies has taught us anything about watching and being watched, it's that we should be more careful.

By Shari Kizirian

More than a century ago, people across the world passed in front of the Lumières' camera. Some stared, trying to divine its purpose. Others tried to avoid the contraption, preferring to slip out of view. Others were indifferent or unaware, never even looking. No matter how they felt about it, it was too late. They were already caught on film. Fast forward to now and cameras peer at us from the corners of elevators, parking garages, cafés, city streets, data piling up by the terabyte with the vague promise of keeping us safe. But viewer and viewer have always needed to beware. The proscription on prying eyes is ancient; Perseus, Orpheus, and the wives of Lot and Bluebeard all got in permanent trouble just for looking. If a century of movies has taught us anything about watching and being watched, it's that we should be more careful. From the keyhole shot in Lois Weber's 1913 short Suspense to James Stewart's telephoto lens in Rear Window, from the deadly tripod of Peeping Tom's 16mm movie camera to Jack Gyllenhaal's unblinking newshound Nightcrawler, watching is downright creepy and quite often deadly.

Watching a Lover: La captive

Like Vertigo's Scottie wheeling around San Francisco in pursuit of his elusive Madeleine, Chantal Akerman's camera is initially in collusion with Simon, closely tracking the inscrutable object of his strange affections down the narrow streets of Paris and the labyrinthine hallways of his creaky-floored home. Using Ariane's friends to secretly control her movements, interrogating her repeatedly about her whereabouts, spying her while she sleeps, Simon is like a CIA agent of love who has tasked himself with catching her in a lie. Based on Marcel Proust's La Prisonnière, La captive is a study in unhealthy obsession and its paltry rewards. ("I see you," Ariane tells Simon, with her eyes closed.) By the end, the prisoner of the title is as much the tracker as the tracked.

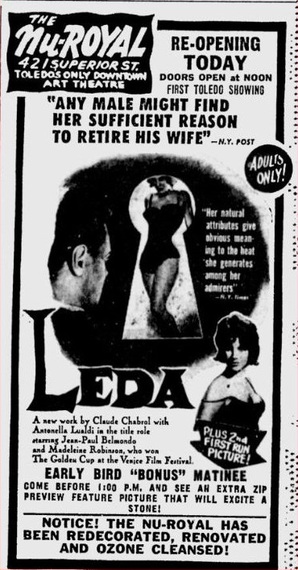

Watching the Family: Á double tour

A little bit Hitchcock, a little bit Sirk, a little bit Belmondo, Claude Chabrol's study of the dangers of looking employs very few reaction shots, keeping the actors in the same frame while they circle each other, plotting self-destruction. The film begins with the oldest transgression of looking, a nearly naked fresh-faced maid hanging out the manor window in her underwear. The gardener watches from the hedges, the son watches through a keyhole, the milkman tells her to get dressed. Meanwhile the mid-life crisis husband keeps his mistress on full view in the adjacent house. The only real love in the house is captured in quick silhouette, a warm yellow glow backlighting a dark stairwell just long enough for an urgent, surprising declaration. Amid it all, a murder still must be committed and then solved. Once the narrative falls skillfully together, whose crime and why were in plain sight from the very beginning.

Watching a Stranger: Gigante

You can't really blame him for watching. It's his job. Beginning at 11 pm, Jara enters the monochromatic midnight of surveillance monitors, keeping an eye on the bakers, the butchers, and cleaning ladies of the graveyard shift. When one of the new staff catches his eye, he begins to observe her outside work as well. Jara learns little about Julia on his stakeouts, but the narrowly framed world he's become accustomed to suddenly opens up into the wide spaces of the day-lit city. Gigante's stalker is largely benign and his creepiness is leavened with humor, when he realizes, for example, that he's hiding beneath a grocery store's security camera. Eventually his spying becomes rather sweet but, as it turns out, altogether unnecessary. He could have avoided it all by simply revealing a bit of himself in the first place.

Watching the Neighbors: The Tenants

In São Paulo's tightly packed working-class neighborhood bordering an even more tightly packed slum of Sérgio Bianchi's The Tenants, other people's lives are inevitably visible. Everybody's watching, through the kitchen's louvered blinds, out the big bus windows, on the television. (One woman pulls up a beach chair on the sidewalk to get a better view.) Valter's the only one who doesn't want to see. When he finally looks it's out of a salacious curiosity, and he learns that secrets are not just what's piled up out back in the dark, but what's right in front of you in broad daylight.

Watching the Watchers: The Prowler

That the state cannot be trusted with even a peephole onto our lives is something Joseph Losey knew in 1951 when he made this film noir. The plot is set into motion over the credits: a shapely young wife alone at night draws the shade against a pair of prying eyes. The cops arrive, and she's got another problem entirely, a uniformed Van Heflin as insistently unblinking as Nightcrawler's Lou Bloom. Later on, creeping around outside the house of the object of his desire, Heflin draws the husband outside. Two gunshots later and we can guess the outcome. When the lovers escape to a ghost town in the desert, their new neighborless view looks out through an enormous gaping hole in the wall -- what's rotten now resides inside and must be exposed.

Those Eyes Watching You: Dans la maison

From The Front Page to Deconstructing Harry writers have gotten into all kinds of trouble for putting "what they know" on paper. In François Ozon's adroit, unjustly overlooked Dans la maison , the precocious teenaged Claude spins a soap-operatic yarn for his homework, basing it on his visits to the house of a classmate, each set of pages ending on a tantalizing cliffhanger. The teacher shares these stories with his wife and they both become squeamishly riveted. Dans la maison pokes at the ethics of looking at someone else's private world, while proving it fodder for comedy and some pretty typical sorrow. Ozon's warning, however, is not so much directed at the teller of tales -- it's the reader who needs to beware.