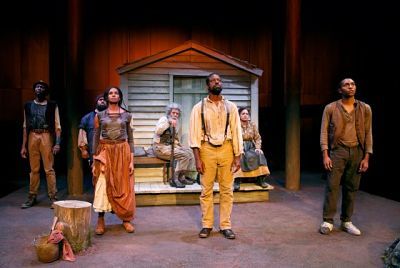

Suzan-Lori Parks' ambitious Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 and 3, is an expansive vision that meditates on the experience of African Americans during the Civil War. The Pulitzer Prize winner for Topdog/Underdog is launching the first three parts of her nine-part serial off-Broadway at The Public Theater.

The play's issues are weighty -- the impact of slavery and the confusion of freedom. Parks' characters are wrapped in a classical framework -- a journey epic -- while the realities of oppression and liberation are layered. Her cast, thanks to Jo Bonney's tight direction, delivers moving performances that evoke empathy and respect.

Part 1 is set on a small Texas plantation in 1862; the "Less Than Desirable Slaves" are betting whether Hero (Sterling K. Brown) will stay on the plantation or leave with the Confederate boss-master (Ken Marks) in exchange for his freedom. Hero's decision will impact the others, especially his beloved Penny (Jenny Jules) and friend/rival Homer (Jeremie Harris).

The master's trustworthiness is an issue, so is the idea of emancipation, since the slaves have no framework -- only longing -- to operate as free men and women. That critical point is brought home in Act 2, when the boss-master and a captured Union captain of the First Kansas Colored Infantry (Louis Cancelmi), and later, the soldier and Hero, discuss the merits of freedom and the racial divide. (Hero is a bit stymied; a slave is worth $800, while a free man nothing?)

By Part 3, Hero, like Odysseus, has to confront his adventures and future -- as do those he left behind. The Emancipation Proclamation, enacted in January 1863, freed slaves in the 11 Confederate states still in rebellion, though enforcement, until the Union controlled all of the South, was difficult.

Sterling K. Brown as Hero is a powerful figure, while Ken Marks' odious boss-master and Louis Cancelmi's captive are excellent. There are equally solid showings by Jenny Jules, Jeremie Harris and the rest of the cast. All characters are nuanced, rather than caricatured, adding to the meaningful discussion: "Slavery, in a way, has nothing to do with the master."

However, the odd clash of grey crocs and modern rejoinders, like "snap," seem out of place in a serious meditation on the struggle for freedom. The linguistic/fashion mix can prove a distraction. Such touches, like the odd comic relief of Odd-See, Hero's prescient dog in Act 3, can jerk a carefully calibrated work off-kilter, however creative the impulse. And at nearly three hours, the play could be trimmed for pacing. But along with Steven Bargonetti's perfect music, it brings a thoughtful, provocative twist to history.

Now considered one of the towering figures of American literature, Emily Dickinson has often been viewed as a modest, old-fashioned spinster. But as The Belle of Amherst at the Westside Theater makes clear, she is insightful, witty, passionate and charming. (Her credo was "Tell all the Truth but tell it slant.")

William Luce's clever play, compiled from Dickinson's letters, diaries and poems portrays a woman of spirit. Far from a reclusive, frightened woman, Emily Dickinson emerges, in Joely Richardson's capable hands, as a charming woman who refused to succumb to evangelical Christianity or social convention.

Richardson, best known to American audiences for The Patriot, The Tudors and Nip/Tuck, gives a captivating performance as the celebrated poet whose compressed verse profoundly influenced 20th-century poetry. The neighbors, she muses, think of her as "half-cracked," but she enjoys posing as an eccentric and chooses to shun society as a form of control. Instead, she nurtured "the light within" in 1,800 poems rejected as too cutting edge for the literary society of her day.

(A full compilation of her poetry wasn't published until 1955, but a few years after her death, in 1890, the first batch of poems sold 11,000 copies in its debut year.)

The Belle of Amherst finds Dickinson musing on love, family, nature, fame and death. The daughter of a depressed mother and stern father, Dickinson had intense infatuations with various married men -- her desire is palpable. She writes to an unknown "Master," imploring him to "open your life wide, and take me in."

Poignant and enlightening, The Belle of Amherst weaves a subtle spell on its audiences. One leaves feeling privileged to spend time with a woman who, contrary to popular myth, lived life on her own terms.

The Belle of Amherst photo: Carol Rosegg