First appeared on Food Riot, by Amanda Nelson

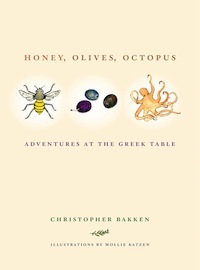

I raved and drooled about Honey, Olives, Octopus: Adventures at the Greek Table over on our sister site, Book Riot, naming it the best book I read in August. Backstory: I don't travel because: lazy/addicted to my comforts/hate airports, so travel memoirs aren't usually my jam, but my local indie bookseller just knew that I would love this book because a) it's written by a poet, and you can tell and b) the whole book is some damn good food writing. And my bookseller (that's right, she's mine) was absolutely right.

I raved and drooled about Honey, Olives, Octopus: Adventures at the Greek Table over on our sister site, Book Riot, naming it the best book I read in August. Backstory: I don't travel because: lazy/addicted to my comforts/hate airports, so travel memoirs aren't usually my jam, but my local indie bookseller just knew that I would love this book because a) it's written by a poet, and you can tell and b) the whole book is some damn good food writing. And my bookseller (that's right, she's mine) was absolutely right.

So I devoured (FOOD PUNS!) the book and contacted the author to ask some nagging follow-up questions. Partially because it's convinced me to go to Greece and I need him to tell me where to go and what to eat. If you're at all interested in terroir, mythology, history, cheese, olive oil, or epic honey, read on. And then get the book.

____________________

So what's Greece got that other countries ain't got? You've been going there annually for over 20 years, you've taught there, you obviously love the food. Why not Brazil? Italy, all Eat, Pray, Love-style? Montana (kidding)?

I'm sure there are some other places on the planet where you can eat a meal (I'm thinking now of almost any meal I eat on the patio of Pension Archontissa on Thasos, overlooking the ruins of an ancient temple, an early Christian basilica, and three stupidly exquisite beaches) knowing that everything on your plate was grown, caught, grazed, fermented, baked, or cooked within one mile of where you are eating it. Trendy concepts like "local" and "sustainable" are simple facts of life in Greece. They always have been.

On top of that, what Greece has got is a highly complicated 3,000 year history that you can both feel and taste. From that patio I mention above, while getting high on tsipouro (a local distillation that I refer to as 'ouzo's evil cousin') and eating chickpeas roasted in the wood oven and some just-caught barbounia (what we call red mullet in English), you can ponder the various levels of that history. They are legible in the actual, physical ruins layered atop one another on the peninsula before you-archaic, Hellenistic, early-Christian, Byzantine, Roman-but also in the dishes you eat while sitting on that peninsula. As I say in my book, "the country's history is written in the elements of its cuisine."

To put this another way: the armies of Alexander the Great were fed on barley, olives and beans. When you go to Greece today, you'll be fed on those things too.

You point out so many instances in the book where Greek food's amazing-ness is wrapped up in the mythology and terroir of the place. So how do you scratch the itch for the food when you're in the states? Do you just suffer with "not good enough"?

Killer olive oil and excellent produce are the backbone of Greek cuisine. With nine months of winter a year in western Pennsylvania, there's not much hope of sustaining my own olive grove. So I horde imported organic Cretan oil and use it with abandon. I also run a CSA out of my garage (working with an Amish farmer), which means I have a direct line to a great supply of local vegetables.

Now, I happen to be a damn fine cook and with these supplies I can make a lot of Greek dishes in my own kitchen. While good, and often really good, they never quite scratch the itch. The missing ingredient always turns out to be Greece itself.

On top of that, there is this suffering: I have a rule that forbids me from eating seafood when more than a mile from the sea. Turns out I'm a complete whore for Greek seafood, so swearing off fish when I'm not in Greece is very hard. But it's worth it. When you've eaten fish just off the boat, no other fish is ever good enough. Not by a long shot. So I eat my beans and bide my time all winter and suffer, then enjoy many a piscatory orgy during the summer in Greece.

I've heard rumors that you've cooked for Michael Pollan. How did that happen? What did you make? Was he awesome?

Michael was visiting Allegheny College, where I teach, and since we live in a town without a single decent restaurant, it was decided that I should cook for him. When Michael Pollan is coming to dinner, you want to embrace his ethos (as I already do, wholeheartedly) in the dishes you serve. But he visited in February. That's a good time for ice hockey and dog-sledding in Pennsylvania, but it's not so good for local produce.

Our local Amish farmer, David Yoder, managed to keep some baby-greens growing in one of his greenhouses. And I had some butternut squash left over from the fall. I kept it simple. Chicken liver crostini for a starter. A huge wooden bowl of baby greens dressed with Cretan olive oil and Lesbian sea salt. Some cauliflower (alas, it traveled from California, like Mr. Pollan himself) browned in oil, then finished with garlic, almonds, currants, and orange. For the main course: handmade butternut squash-and-walnut cappellaci tossed with brown butter and some sage I dug from a snowbank.

Michael was gracious and inspiring and kind and extremely thoughtful. Turns out he's been subjected to a lot of well-meaning, if bizarre and inedible dinners while traveling around the country. So I was relieved when he told me it was worth coming to Meadville for my cauliflower recipe alone.

Speaking of whole foods/slow food, one of the reasons the Greek meals you describe sounds so amazing is the seasonal freshness -- everything's pulled from the earth or the sea or the field same day. Greek food seems minimally processed. How long do you think such traditional slow cooking will hold out against modernization, globalization, and the ease of corporate processing?

This is an excellent question and one that goes to the heart of what I wanted to explore in Honey, Olives, Octopus. While I think my book is rather a boisterous romp most of the time, it's got an elegiac side to it as well. For each chapter, I went in search of the finest elements of the Greek table -- olives, bread, cheese, beans, etc. -- and wanted to learn how they came into being. Typically, this involved working with older women in remote locations. What will happen, I wondered constantly, when this generation of culinary elders disappears?

KFC and McDonald's have set up shop in Greece's larger cities and for the first time obesity (of the sort we know a lot about in the U.S.) is becoming an issue there.

Ironically, the country's economic meltdown, which has incredibly serious implications for everyone living in Greece, may turn the youngest generation back to their grandparents' culinary principles: gardening, foraging, efficient slow cooking, working with one's hands. As in Italy, where they embrace the idea of la cucina povera, Greek cuisine came into being at the intersection of poverty and necessity. With salaries and pensions slashed, many people are now returning to the hills, remembering how to gather wild greens and how to make a pot of chickpeas feed a whole family, when just a few years ago they were eating most of their meals at restaurants. Greeks are survivors. Tragedy often returns them to the bedrock of their cultural and culinary values.

You mention in the book that you couldn't bring yourself to attend a lamb-slaughtering on one trip. There's been recent news that octopuses are as smart as dogs- does that make you hesitant to eat them?

Being in the sea, which for me often involves swimming around in deep water with a spear gun, gives me tremendous pleasure. I find diving for octopus thrilling. And I find them delicious.

I have great respect for all the animals I eat, especially the octopus. They completely fascinate me. While the ethical nuances of my choice to eat animals are surely selfish and under-complicated, I believe I should have the courage to harvest animals myself now and then, so I know what's at stake. I also practice restraint. I never take more than one octopus a day and I only take large ones, those nearing the end of their life span (octopuses don't live long, in spite of all that intelligence).

I actually have a tattoo of an octopus on my forearm to remind me what it means to do this. I do not take my octopus hunting lightly.

In the section on honey from Kythira, you mention that the bee colonies on the island are thriving. Another Riot contributor asks: "Does Europe have the same pesticide problems we have? Does Greece take any steps to protect their bees? Is there hope?"

In many parts of Europe, farmers have rallied together to ban genetically-modified crops and consumers there have rejected their use in food. Pesticides are still widely used across Europe, though there's less super-scale farming going on there, which makes a difference.

Colony-collapse disorder has hit Europe, just as it has hit much of the planet. It's not entirely clear what causes this, though right now most scientific fingers are indeed pointing in the direction of Monsanto's Frankencrops and the overuse of insecticides.

And colony-collapse disorder (CCD) has also hit parts of Greece. But it has not yet come to Kythira. The island's agriculture is almost completely organic and most of the bees are kept stationary (in other words, the hives are not moved from place to place, as they so often are in the U.S., being trucked from farm to farm and state to state). That seems to make a difference.

The land ethic practiced by most of the farmers and beekeepers on Kythira is absolutely inspiring and I left there with a lot of hope.

I can't say I see that kind of land ethic replacing the 'big business' attitude toward farming in the U.S., but a continued and fervent turn in the direction of organic and local at the grassroots level might allow us to hold out some hope for the bees.

Either way, CCD terrifies me. It should terrify us all.

I've never been to Greece and hate traveling, but it's now got a top spot on my bucket list after reading your book. Where's the first place I should go and the first thing I should eat?

I am immediately tempted to describe a decadent meal by the seaside featuring 20 artisanal and niche products you'd have never heard of. But if you really want to taste the essence of Greece, I suggest the following to blow your mind.

Go to Kythira and find a man named Michalis Protopsaltis in the village of Mitata. He goes out in the morning and picks wild greens (a.k.a. weeds) from between the rows of his organic vineyard. These he will boil until tender and then drench with the green, scratchy olive oil his son Byron makes. They harvest a lovely salt on the island too (think Kythirian fleur de sel) and so you should sprinkle a bit of that over the greens. Maybe a squeeze of lemon too. Within reach on the table there will be a neighbor's cheese and probably some bread just from the wood oven. And a plate of little black olives. When you have sampled the olives, cheese, and bread, and have eaten the greens, lift the plate from the table, tilt it to your face, and drink the remaining oil.

That should get you started.

_________________

I think I'm going to take that advice.