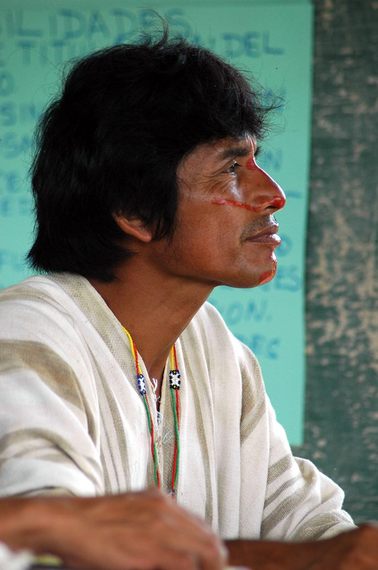

Edwin Chota was one of four members of the Ashéninka people murdered in the Peruvian Amazon last week for the sin of protecting the forest. But Chota was more than just a leader. He was a father, a husband, and a friend. Here we remember him, in his words and our own memories.

Edwin Chota at a meeting discussing

the practices of sustainable timber harvesting.

Photo: Emory Richey

Always carrying a sheaf of legal documents and maps, Peruvian indigenous leader Edwin Chota tirelessly traveled from his native community of Alto Tamaya - Saweto to the city of Pucallpa, Ucayali, using the seven-day boat trip as an opportunity to plan his next steps.

"Saweto will host an event on indigenous sustainable development at the border, and we want as many people as possible there," said Chota, a 52-year-old chief of the Ashéninka people shortly before he was murdered last week by loggers intent on harvesting timber in the forest he fought so hard to protect. "Everyone from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the president of Ucayali needs to attend."

Chota dreamed of a borderland Amazonian forest with indigenous people thriving alongside the region's biodiversity. He envisioned a new generation of indigenous families living in peace while teaching others at the border how to protect and use the forest. In Chota's dream, Saweto would become a model indigenous community leading the way towards a more sustainable Amazon.

Both of us had the honor of working beside Chota as advisors and in our capacity with the Upper Amazon Conservancy and ProPurús - two of many NGOs Chota had engaged to help him save the forest he loved so dearly. We spent last night going through our notebooks, sharing bits of wisdom scribbled on the trail.

"All the leaders who are active today will one day be gone," he said presciently. "But our dream will stay alive as long as we set the ground for the children walking behind us."

Yet, as we write these words, his widow and his orphaned children have fled the ground he set for them. So, too, have the widows and orphans of the other three leaders murdered by loggers intent on harvesting every last valuable tree in the rainforest.

Chota fought endlessly to build a more participatory and ethical form of indigenous leadership in Peru. Only such leadership, he believed, would secure the future of today's indigenous children at the border.

His concern for his children and Saweto's youth lay at the core of his efforts to obtain a legal land title and end illegal logging in his territory. Starting in 2002, he delivered over one hundred letters to as many governmental officials as he could demanding birth certificates, a better school, and adequate health facilities for his community. His life project encompassed every aspect needed to build thriving borderland communities.

Chota didn't merely hope for a land title, an end to illegal logging, or financial prosperity for Saweto. He desired a peaceful future for his family, his community, and anyone else who shared his dream of a better Amazonia:

"You have to work for a goal larger than what you can see for the coming years. We walk and travel through the forest because we want this place to exist without danger or violence in fifty, one hundred, or even five hundred years."

These aspirations and his endless energy gave Chota a special ability to build relationships across communities, regions, and countries. More than an international support network, Chota developed friendships with supporters everywhere from the United States to Guatemala, from Germany to Brazil. He believed in the relationships he built throughout the past decade, as this passage reminds us:

"Nothing will defeat us if we stay together. I feel stronger with a network around me. It does not matter who the face of the network is. All that matters is that we push and walk together."

Yet, as we read these words of hope, we can't help but remember that the man who spoke them was murdered by people who had no such sentiments and who harbored no such love for the forest or their fellow man. One sentence chills us to the bone. It's from a piece by Scott Wallace, who profiled Chota in National Geographic last year:

"Someone from Saweto will die, and I will denounce you as a drug trafficker," logging boss Hugo Sorio Flores allegedly told Chota...

At the time of his murder, Chota was preparing to bring his community's case and a complaint against illegal loggers to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. At home, his main goal was to keep Saweto's youth hopeful and united. Every day Chota was a father, a community leader, an environmentalist, and an international indigenous rights defender. He embodied each of those roles with incredible courage, passion, and conviction.

Yesterday we learned that he is gone, but his words - and his dream - live on. So will the forest and homelands he fought to protect, but only if the rest of the world demonstrates the same courage and conviction as this gentle warrior.

About the Authors

Diego Leal works on transboundary indigenous politics in the Peruvian-Brazilian border. He worked with Edwin Chota on Saweto's land titling process for the past two years and a half.

David Salisbury is an Associate Professor of Geography at the University of Richmond. He began to work alongside Edwin Chota in 2004. His research focuses on the peoples and nature of the highly contested Amazon borderlands.