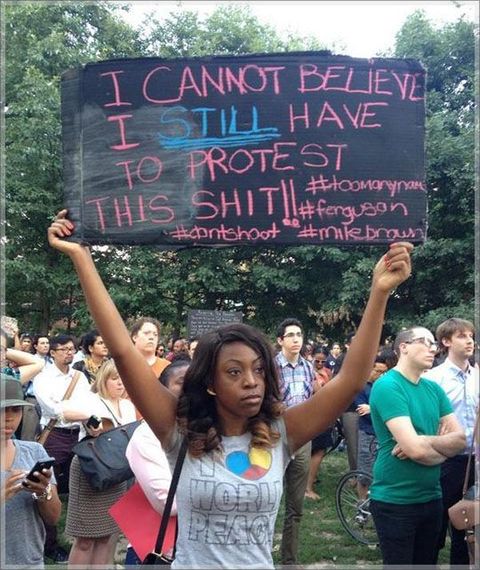

Last month, a young activist named MarShawn M. McCarrel committed suicide on the steps of the Ohio State House. Although I was never acquainted with this young man, the news struck close to home. Having added my voice to the Black Lives Matter movement and been at the forefront of the #Rights4ALLinDR movement, I was all to familiar with grassroots activism: the long nights spent strategizing, unreasonable expectations placed on those in leadership roles, the few support networks to help reinforce good strategies and ideas, the petty infighting amongst supposed allies, and never having enough time or money to accomplish goals that seemed both self-evident and insurmountable all at once. In "the movement", the wins are often thankless and unseen, yet the losses can be overwhelming. As I learned more about MarShawn's exemplary life, I was reminded of everything I'd recently walked away from when I left the United States.

In June 2015, the Dominican Republic geared up to round up people of Haitian descent within the country- whether born in the DR or not- and executed a political program of ethnic cleansing so sophisticated that we activists and legal scholars spent a week solely reviewing international law to find any precedent for what would soon take place. Suddenly on panels, national television, and on the blowhorn at protests seemingly all at the same time, I was propelled to the forefront of this human rights issue. Sleep was rare as our grassroots campaign gained steam and the Dominican government responded with an aggressive lobbying, public relations, and social media campaign to counter the idea that people of Haitian descent could have any human rights in the Dominican Republic.

Working around the clock, we did not have funds to pay the experienced staff needed to do this work. We relied on the passion of volunteers and I filled in the gaps. When the person who was responsible for making the flyers could not meet the deadline, I stayed up all night and designed a flyer. When the people responsible for setting up meetings with Congressional offices dropped the ball, I stepped in with a colleague of mine and we called and emailed Congress on our lunch break two weeks before a coalition of organizations joined us on Capitol Hill.

"The movement" fueled my passions but it did not pay my bills, making it necessary to also maintain a demanding yet unfulfilling career in international development- a field whiter than the Oscars. A difficult truth that is scarcely discussed is that national and foreign policy are largely shaped by white men who've scarcely ever seen a ghetto, stepped foot in a favela, or tried to stretch a minimum wage salary until the end of the month. The disconnect between those who craft policy and those who live through their impacts cannot be understated. It is the reason behind the criminalization of drug addiction rather than rehabilitation, or why the Clinton Administration's forced Haiti to lower its tariffs on basic goods so that that country's farmers were forced to abandoned their farms, unable to compete with cheaper rice coming from the subsidized U.S. farmers.

The amount of people of color working to shape the policies that impact the lives of poor people of color, both in the U.S. and abroad, are so few and far between that, on more than one occasion, I've walked into meetings only to be mistaken for the catering staff. Thus, casual racism about brown and black people was common, even to the extent that it was codified into reports and country strategies at times. Sexism about a woman's role in a field that required you to go into remote and underdeveloped areas to be able to advance your career shaped how people treated me. I had to be outstanding: the smartest when others barely knew the historical background of the country we were meant to be "uplifting from poverty"; well-dressed, but never desirable even when others mistook a mini skirt and a blazer for "business casual"; a polyglot when my some of my colleagues could barely speak English properly; articulate, but never "loud or aggressive" with my opinions so as not to intimidate white people. I was all these things and more, only to realize that they do not want me there anyway.

As my work environment became more and more toxic, however, and older black woman implored me to simply suck it up, "Do you know how many black women sacrificed for you to get a seat at the table? If you leave, who will represent us?!" For fear that the door would close behind me for all the other black people to come, I was expected to remain in a situation with no support system and little possibility for improvement. The pressure to remain "in the struggle", to allow the fight against injustice- real or perceived, small slights or institutionalized dehumanization- to become the driving force behind every aspect of my life was overwhelming. Many believe that removing oneself from the movement or a toxic environment when "the struggle" is nowhere near won and equality is nowhere near achieved is tantamount to treason. I would be letting black people down if I walked away from challenges few even had the opportunity to be presented with.

To be the only black face with a hard-earned seat at the hostile table by day and force behind a grassroots movement by night was a lonely experience. The long hours meant that "self-care"- a theme commonly preached amongst activists but rarely practiced- was unheard of. Ultimately, it was the broken hearts of Nina Simone and the Black Panthers that convinced me that I needed to aggressively invest in self-care. In the documentary What Happened, Miss Simone, I watched in horror as Nina experienced a mental breakdown as her environment became more and more hostile.

In Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, I saw how making "the movement" their sole purpose forced them to become more and more insular, some rarely even saw their own children. That level of alienation is the thing I feared the most about the call to be a leader. Before I fell too deeply into the rabbit-hole, I decided to move forward with my plans to take a hiatus and move abroad. When I look back on my life, I want to reminisce with memories tinted with joy rather than accolades tainted with oppression.

When I left the institutionalized racism, crumbling infrastructure, five-year presidential campaign cycles, and anti-immigrant sentiments of the U.S. behind, the pushback from friends, colleagues, and strangers alike was immediate. I still get anxious, last minute emails from organizations expecting me to get on a plane and speak on their panel. However, I am deeply content with my decision to take this time to focus on myself. I came to terms with the fact that I wasn't going to change the world right now, no matter how much I sacrificed.

Removing oneself from the struggle when "the struggle" is nowhere near won is necessary at times- and that is okay. Investing in self-care and your interests outside of "the movement" provides an opportunity for new leadership to step up and for the veterans to take a step back and recuperate. Make the selfish investment in your own personal growth that is integral to becoming a stronger leader. MarShawn's suicide is a reminder that self-preservation is necessary for our movements, or passions, and our activism to survive.