Interview with Frances Moore Lappé by Anna Lappé

Among today's most shocking truths is that millions of people go hungry while food production per person climbs. But why... and what can we do? Are any current strategies to combat hunger working? And what lessons can help speed our progress?

Among today's most shocking truths is that millions of people go hungry while food production per person climbs. But why... and what can we do? Are any current strategies to combat hunger working? And what lessons can help speed our progress?

The organization charged with helping us answer such questions is the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). In an important new report, "Framing Hunger," seven hunger-related organizations and seventeen U.S. and Canadian development scholars and advocates (including my mother, Frances Moore Lappé), challenge ways the FAO defines hunger and communicates progress. So I sat down with my mother to get at the heart of their concerns.

Anna Lappé: Let's start with the most basic question. How does the FAO define hunger?

Frances Moore Lappé: Probably not like most of us do. In the agency's latest annual overview of hunger, the State of Food Insecurity in the World 2012 (SOFI 12), the FAO defines hunger as an "extreme form of food insecurity" in which the calories you eat don't meet "even minimum needs for a sedentary lifestyle" and you survive like that for "over a year." Using this definition, the agency arrives at its hunger total--now 868 million (rounded by the FAO to 870 million), or 12.5 percent of the world's people.

Anna: What's your concern about this definition?

Frances: I was taken aback. Though I've tracked the hunger problem for decades, I had no idea the agency's definition of hunger is so limited. To me, it seems certain to miss millions more who don't experience such long-term, extreme deprivation but who are still without the food they need.

A hunger threshold based on calories needed for sedentary living also seems disconnected from the real world. Roughly three-quarters of the world's undernourished live in the countryside where most people farm or work as day laborers, and the FAO acknowledges that "arduous manual labor" is common in the developing world.

Plus, since FAO's measure of hunger only captures those suffering for "over a year," it doesn't account for people who endure shorter periods of privation, for example, between harvests, or as the result of price spikes, conflict, or weather-related crises. For young children, even short-term nutrient deficiencies can cause lasting harm.

Anna: The title of your report is "Framing Hunger." What is the "frame" about hunger that the FAO uses--and that the mainstream media echoes?

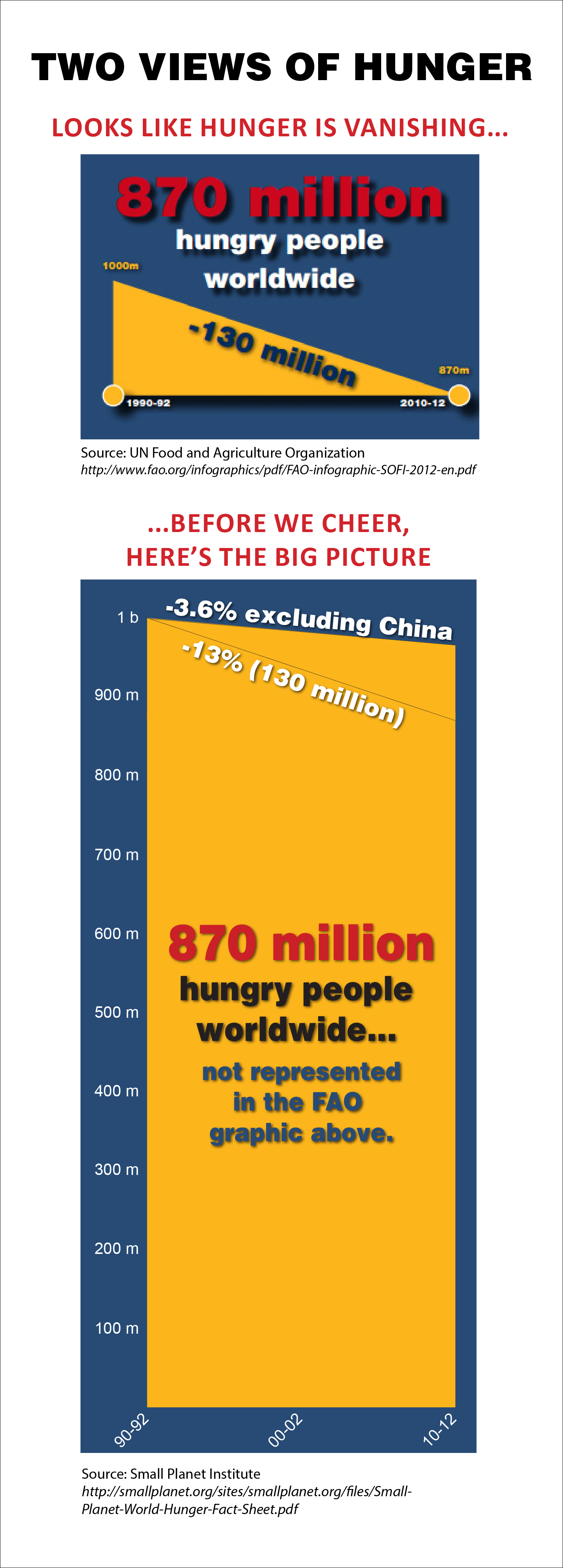

Frances: The FAO presents the current total of 868 million hungry -- a drop of 132 million since 1990 -- as "global progress." The agency's emphasis, spread widely in the media, is that the Millennium Development Goals' (MDG) target of cutting the percentage of hungry people in the developing world by half by 2015 is "within reach," if economies recover from the recession. And, we're already three-quarters of the way there.

Anna: In a world looking for positive news, I can see why this story has spread. What do you think is missing?

Frances: Much of the FAO's positive message follows from a drop in the percentage of extremely undernourished, from about 23 percent to about 15 percent over twenty years. But here's my concern about celebrating the percentage decline: telling hungry people that they're a smaller slice of the whole is surely not much comfort to people without enough to eat.

If the MDG goal were based on the absolute number rather than percent decline, we would only be one-quarter of the way there. It amounts to a 13 percent drop in number, which certainly doesn't feel like a huge success to me. Moreover, the gains have been extremely uneven. Advancement by China (-96 million) and Viet Nam (-24 million) amounts to 91 percent of the net numerical drop; and most of that decline took place in the 1990s. Of course, hunger in other countries declined as well--largely offset by worsening realities elsewhere. But excluding these two countries, over 20 years the number of hungry people has fallen by less than 1 percent.

It's far too early to pat ourselves on the back. So it's disturbing to see a flashy infographic on the FAO's official online hunger portal, part of which we include above, where the declining trend line is so steep that hunger actually appears to be vanishing.

Anna: How do you think the FAO should frame the story of hunger?

Frances: The agency should make it much clearer that its current total represents only those experiencing "extreme" and "chronic" hunger--so people would realize that if measured by a more common notion of hunger, the total would be much higher. When I wrote Diet for a Small Planet in 1971, I could never have imagined that four decades on, we'd still face massive hunger, despite enough food for all and 40 percent more produced per person than when I wrote that book!

Anna: You and your colleagues have communicated with the FAO about your concerns. Is the agency changing the way it frames the hunger challenge?

Frances: For the first time in the SOFI series, in its 2012 volume the agency presents the consequences of basing its hunger estimate on calorie requirements at different levels of activity--but, unfortunately, only in an annex that most readers probably skip. We've been heartened that since SOFI 12's release last fall, the FAO has continued to develop its measures and updated its online Food Security Indicators. It now encourages us to see hunger as a range, from the chronic and severely undernourished 868 million to a larger number the FAO calls "food inadequate," which climbs as high as 1.3 billion people* -- a number 53 percent greater than the agency's publicized hunger total.

Anna: What do you think is a more effective frame for what it will take to solve hunger?

Frances: That gains have been extremely concentrated, and that we live in a contradictory era -- one of huge retreats and impressive advances, even in unexpected places. But the agency largely focuses on the aggregate view, referring, for example, to Africa as a "battle" that we are "losing." Yet, Ghana actually achieved the world's greatest numerical progress--an 87 percent drop in the number of hungry since 1990-92; and seven sub-Saharan countries together cut the number of hungry people by a rate at least 60 percent greater than the global average. At the same time, the Democratic Republic of the Congo experienced a dramatic increase in the number of hungry, but the country is only mentioned in a footnote.

It is in probing just such striking contrasts--where the real lessons live--that the FAO can make its greatest contributions to solving hunger.

Anna: What's been the FAO's response to your group's report?

Frances: Even though "Framing Hunger" is critical of the way the FAO measures and communicates hunger, I want to emphasize how much its authors appreciate the agency's vital work, especially that which supports smallholder, sustainable farming.

Our desire for the agency's success is a big part of what motivates us. So we shared our concerns with the FAO before making them public, and we've been impressed and pleased that the staff has engaged with us, offering helpful clarifications. We're also encouraged that the agency is developing an additional way to capture the scope of hunger. Called Voices of the Hungry, it is an experience-based food insecurity scale involving 15 questions to be added to existing national surveys and rolled out globally next year.

Our fear is that the agency's current framing could encourage both development agencies and the public to believe that "business as usual" is working, when it is not. So we hope our perspectives help spur those both within and outside the FAO to better convey the much more sobering--but richly lesson-filled--reality of the ongoing tragedy of hunger amid plenty.

DON'T MISS our graphic World Hunger One-pager.

*At this site download the data. Go to Tab V15 for percent of world's population who are food inadequate (19.1%). Then go to Tab VA02 for world population. Multiply 19.1% by 6.974 billion.

About Frances Moore Lappé and Anna Lappé: Frances Moore Lappé is the author or co-author of 18 books including the three-million copy Diet for a Small Planet. Her most recent work is EcoMind: Changing the Way We Think to Create the World We Want. She is a Right Livelihood Award recipient and founding member of the World Future Council. Anna Lappé is a national best-selling author of three books and contributing author to twelve more, and a leading voice for sustainable farming. Both Lappé's are founders of the Small Planet Institute, a collaborative network for research and popular education seeking to bring democracy to life.