All images courtesy of Quai Branly Museum

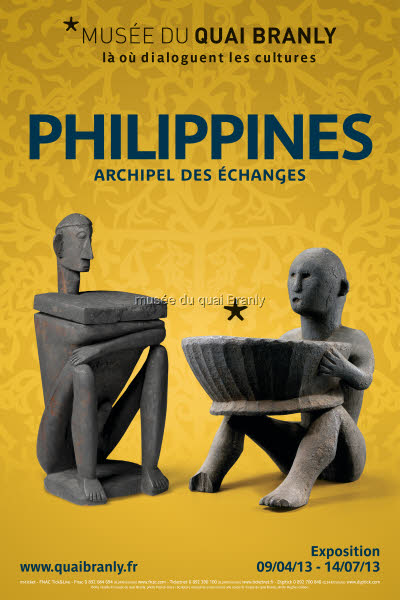

If you're lucky enough to have spent a few months bouncing among the 7000 islands that make up the vast oceanic territory we call the Philippines, you'll have doubtless noticed something extraordinary about this civilization whose artifacts date back some 60 thousand years: there is virtually no ancient architecture. But if you drop into the meandering ethnographic art museum here called the Quai Branly, you will find a stunning array of exquisite and intimate pre-colonial objects from the daily lives of the islands' kings, queens and warriors.

It took Constance de Montbreson five years to put the show together, equally drawn from museums--mostly American--and private collectors. She quickly acknowledges how little she knew at the beginning of the project--and how stunned she was at what she discovered. "When I bega to discover how grand, how extensive [Philippine classic] art is, how well done is the technique, the craftsmanship, it's . . . it's vibrant. The battle shields, for example are like textiles, well adorned. They're gorgeous."

And to western eyes familiar with heavy Roman metal shields or contemporary US SWAT team battering shields, the material may seem equally startling. They are largely constructed from one of the world's most durable woods--bamboo.

Wood of various kinds--often strains of mahogany--forms the basis of most of the large ancient objects since, aside from precious metals, there are few stones in the islands. The woods on the other hand have managed to survive the millennia, like this finely wrought rice scoop below.

.

"It's all very human, the objects [were] very close to human beings, de Montbreson said. This population didn't build any stone architecture. It's in wood. They didn't have.... Only built with wood. They do their homes with mats. It's very fragile material. The wood they use (Naha) is very strong. Indestructible."

Among the most remarkable are the betel nut boxes (betel nuts, recall from the song "Bloody Mary" in the musical South Pacific are prolific throughout the South Pacific) used to contain precious family objects, like gold bracelet and belts offered as obligatory gifts in marriage exchange rites.

Aside from the beauty of the generally small objects in the show is what they reveal of the ancient and even of contemporary Philippine culture and spirituality. As brigandage and tribal warfare broke down the ancient overland silk and spice routes, the Philippines became a maritime crossroads between East and West--from China and Japan to the Arab and African sultanates and Mediterranean empires. Value among the Filipinos became rooted in the value of exchange. Gold, precious stones and fine woods, of course, but as de Montbreson notes, the idea of exchange was equally spiritual and engaged all forms of life.

"When in your mind you project a wish, a prayer, or [sacred] offerings, exchange is everywhere. In spiritual exchange in daily life the place of men and animals are always linked, interconnected by more powerful spiritual forces. You need need to respect this power because you don't know where it comes from. In Fugao, for example, they have more than 150 deities--so you can imagine how precise each situation is governing daily actions that are always connected with the invisible world. It's a huge pantheon--and it's also another form of exchange.

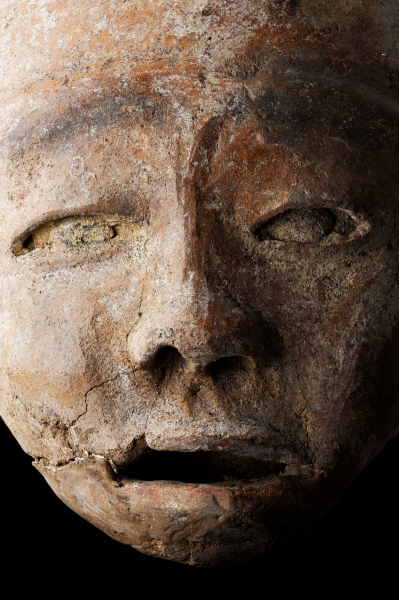

"It's completely animist. You have rules [governing exchange] for human beings, but you also have rules for plants and animals...not in law, but larger rules requiring respect for animals, for ancestors. All of that was present in everyone's daily life, all the time." Funerary jars imported from China were used to store the skulls or petrified heads of revered ancestors. (Of course, since head hunting was once common, some of the detached skulls may be battle prizes--also valuable for exchange.)

One of the most important rules of exchange, not surprisingly concerned the planting, cultivating, harvest and distribution of food and its exchange. Riches were measured both by the quality of objects they had been able to exchange from abroad but often more importantly by the quantity of rice you grew.

"If you are rich and you have a good harvest, she explained, "you must organize a feast to feed the people. You will kill some pigs, some chickens and share them with everybody."

And if you refuse? I asked.

"You cannot be respected if you don't feed the people. If you feed the people they owe you a debt. So you control them. That's the oceanic world. The people are happy. You allow them to cultivate your rice field. They keep some. They work for you. Like Europe in the Middle Ages. Now it's not like that, but it used to be."