When I discovered that Anselm Reyle regarded Jeff Koons--he of the $33 million steel tulips in Las Vegas and the grotesque Puppy topiary at Bilbao--as one of the masters of contemporary realism, I thought about canceling the trip to Grenoble to see Reyle's latest installation of neon tube sculpture and recycled teacups. Good thing I didn't cancel. If Koons has found his ideal home in Los Vegas, Reyle, who's still little known in America, deserves a serious place in contemporary galleries and museums.

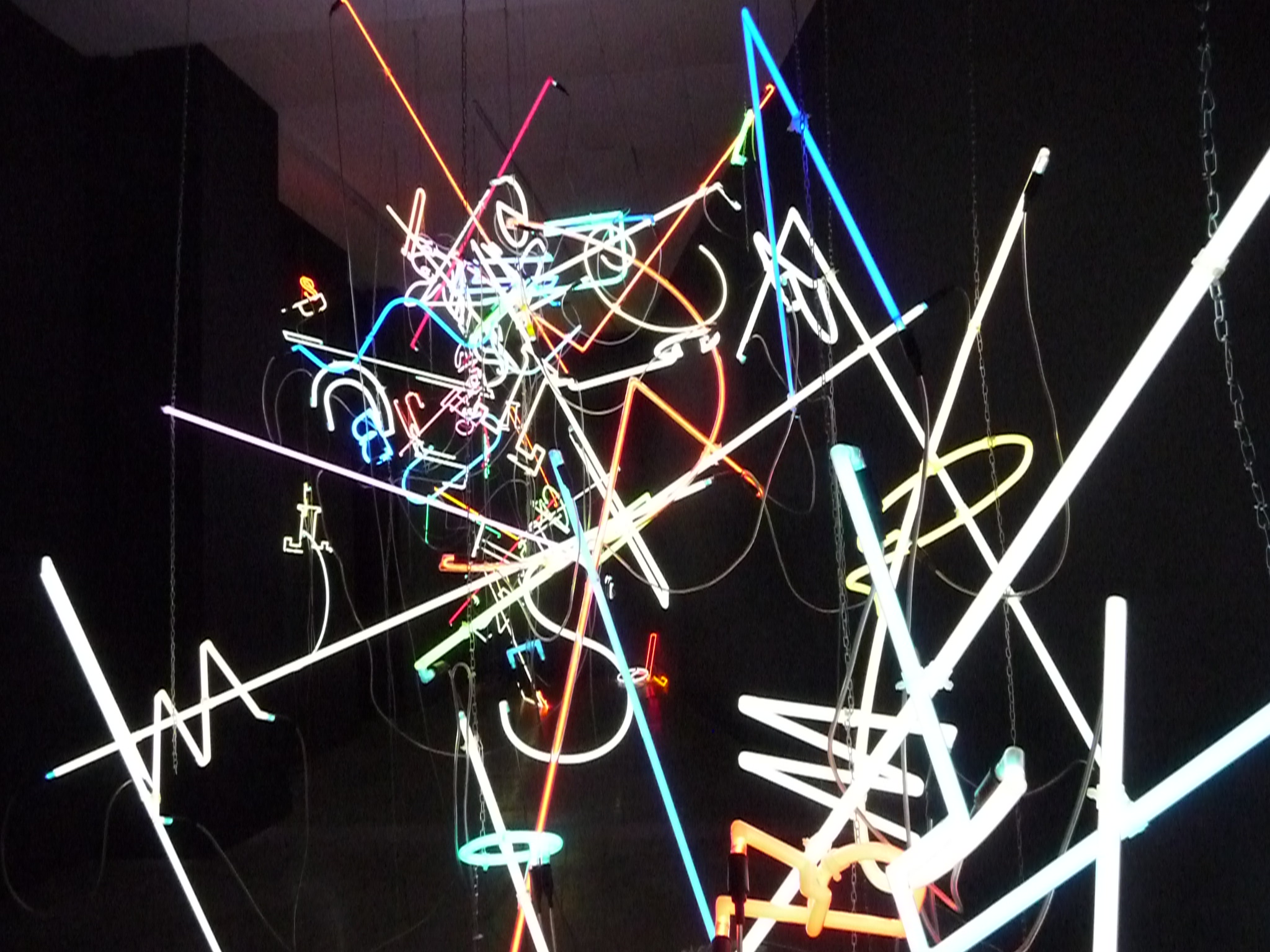

Reyle's current show is in the old metal works building where Gustav Eiffel built the Eiffel Tower (before the building was dismantled and shipped to Grenoble a century ago). Now, it's a huge, breezy place that calls itself Le Magasin, Grenoble's National Center for Contemporary Art. It houses the biggest show Reyle has mounted outside Germany, where he divides his time between Hamburg and Berlin. Reyle is at once a fierce modernist of the abstract school and a dedicated recycler. Sometimes the two tendencies seem to be at war--though not in the opening monumental nest of neon chaos built of serpentine tubes that include elements of words, an apparent heart and a "bunny" rabbit.

Mid-way through a visit to Le Magasin last month Anselm Reyle arrived to talk about the show, which overall he characterized as "fragments of our current civilizations and its rejects." Responding to one person's question about the neon tubes, he smiled, "Yes, you can think of it as a child's messy bedroom too."

In the next room are two displays (he has more) of his broken tea cups, which he discovered in a bin at the Meissen porcelain factory, Europe's leading porcelain maker. The pieces, all of which had faults, were set to be destroyed and recycled, but Reyle persuaded the company to paint them with grandmotherly roses and glaze them all into a single piece, including a set of cherub's legs. It's the epitome of kitsch cliché, but under the glow of an overhead spot in the dark, it's at once disturbingly attractive and repellant.

"It's clichés that create a connection between us all," Anselm says, describing the great part of his work as a deliberation on how we have all become inundated through media and mass marketing in a plastic rain forest of clichéd images and objects. The approach, first explored 80 years ago by Yves Klein (the famous blue paintings and empty glass cases) and the Franco-Hungarian painter-sculptor Victor Vasarely, who constructed brightly colored off center cubist blocks) are seen as pre-cursors to the op-art movement a generation later.

Following in their tracks, Reyle said he'd been possessed since childhood with scenes and objects that raise the question, "What is realism?" Not just in art but in everyday life. How do we distinguish the real from the fabricated? What and where is the stock of fragmentary (or full) that fill our visual cortexes?

"You know, my parents gave me wooden toys [when I was growing up in the Seventies]. They were all very good taste, but I was always more interested in the kitsch commercial toys." Like plastic fire engines and rubber bunnies. If his visual, playful interests were hard for his Sixties-era parents to accept, Reyle says his (and Koons') deliberation with kitsch is equally problematic for the established art world. "The art world doesn't like addressing kitsch; kitsch is badly received. The plasticized stands [he points the bases on which his objects are mounted] = kitsch = cliché. But they're all part of the piece."

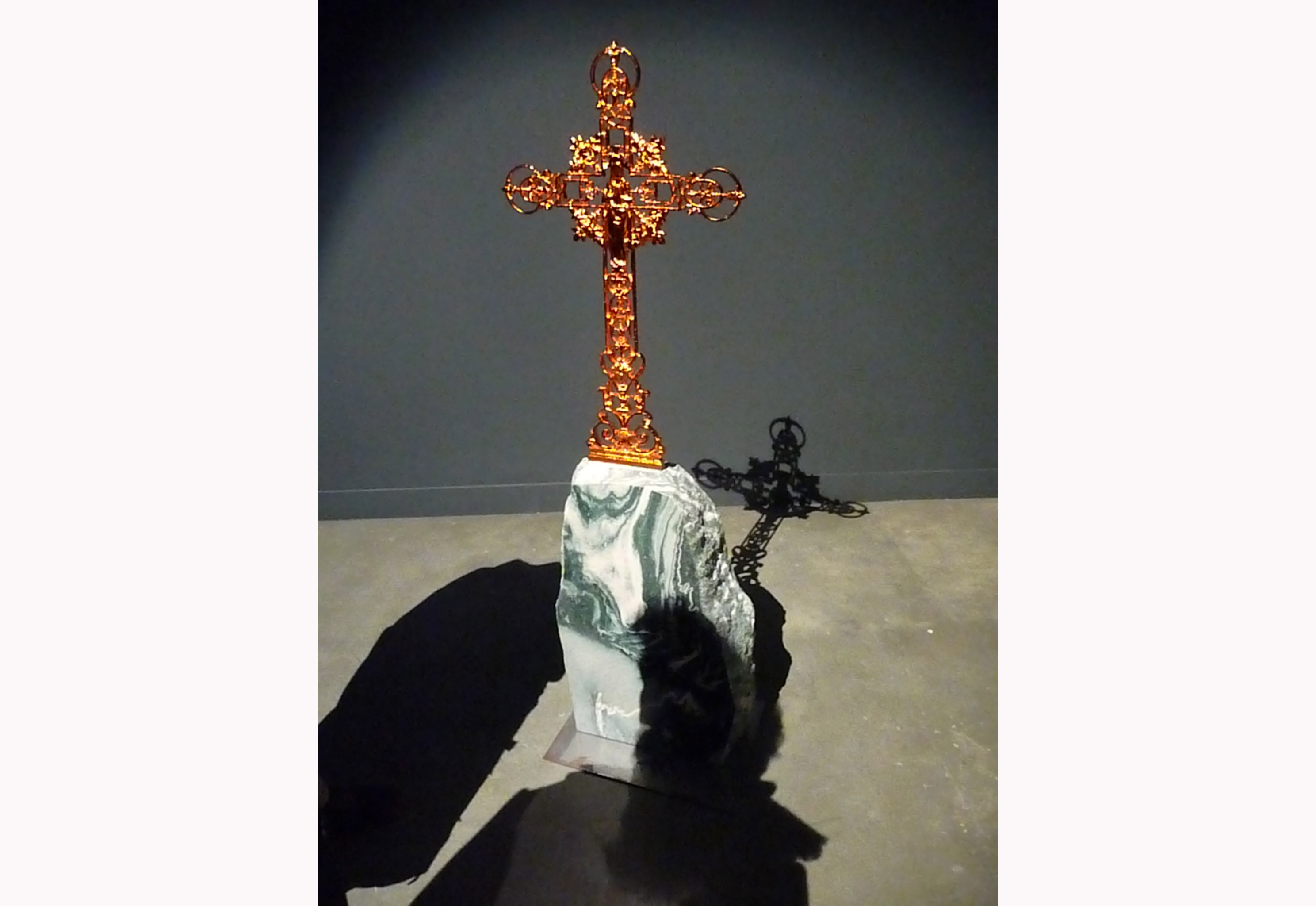

We pass by a tacky abandoned cemetery cross he found in a junk shop. He gilded and lacquered it. It stands alone in an intense light casting a shadow of abandonment on the dark floor and wall.

In an interview with Friedrich von Borries, Reyle is very clear that he always works in collaboration with other artisans and never searches within himself for the sources of either his paintings or his sculptures: "Everything I make, all my artistic work, is based on something pre-existing. Whether it's foil I've found in a storefront window, or found images from recent art history . . . . Or African artisanship, or even Punk welding art from '80s Berlin. . . . The basic idea comes from something that's already there."

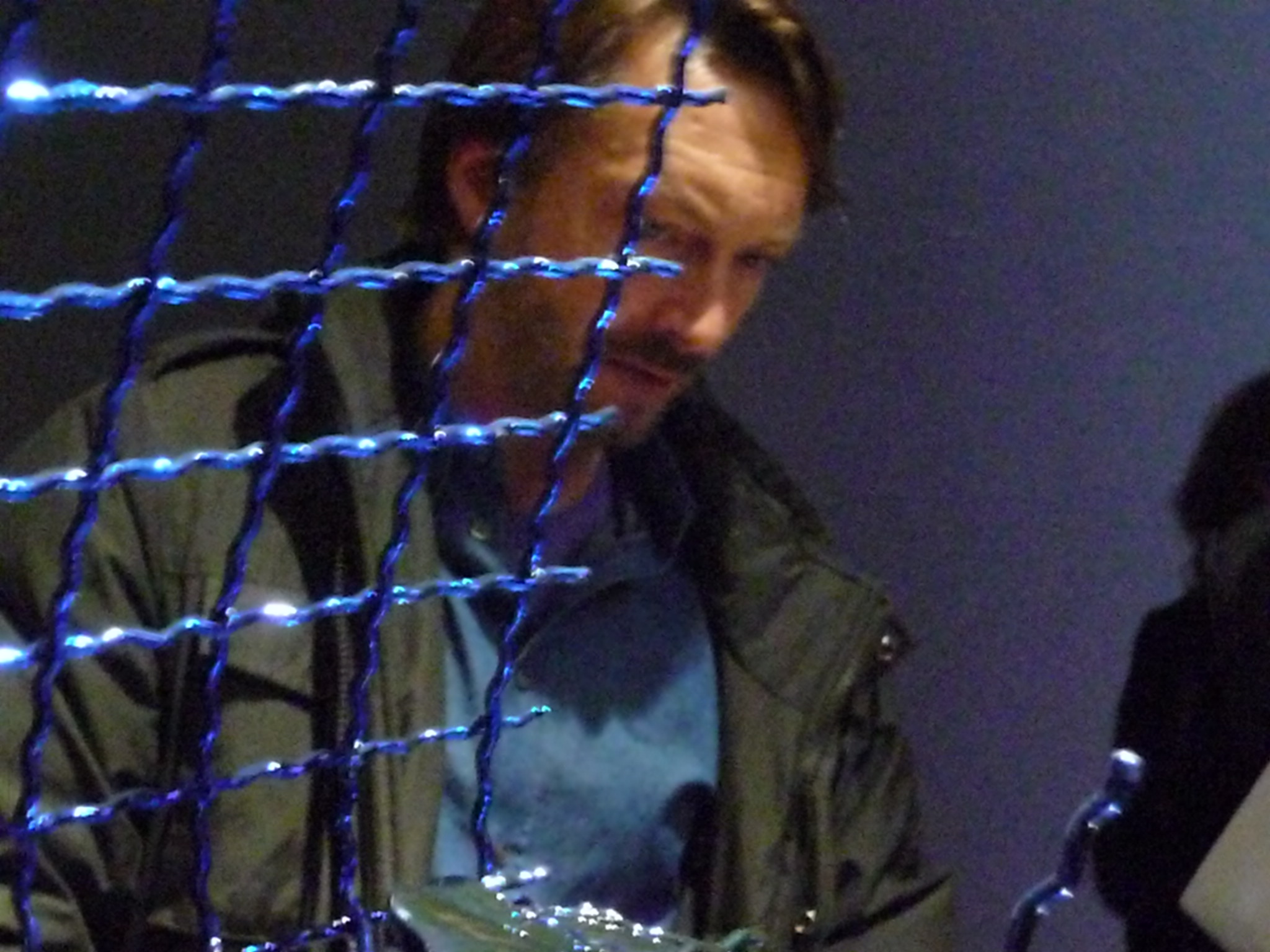

Three "sculptures" of ordinary clay blocks stacked helter-kelter and pierced by a giant metal screw, then cast in bronze and colored in multiple highly chromatic colors in a machine shop refuse to be ignored. (Reyle stands behind a wire mesh in super-saturated blue.)

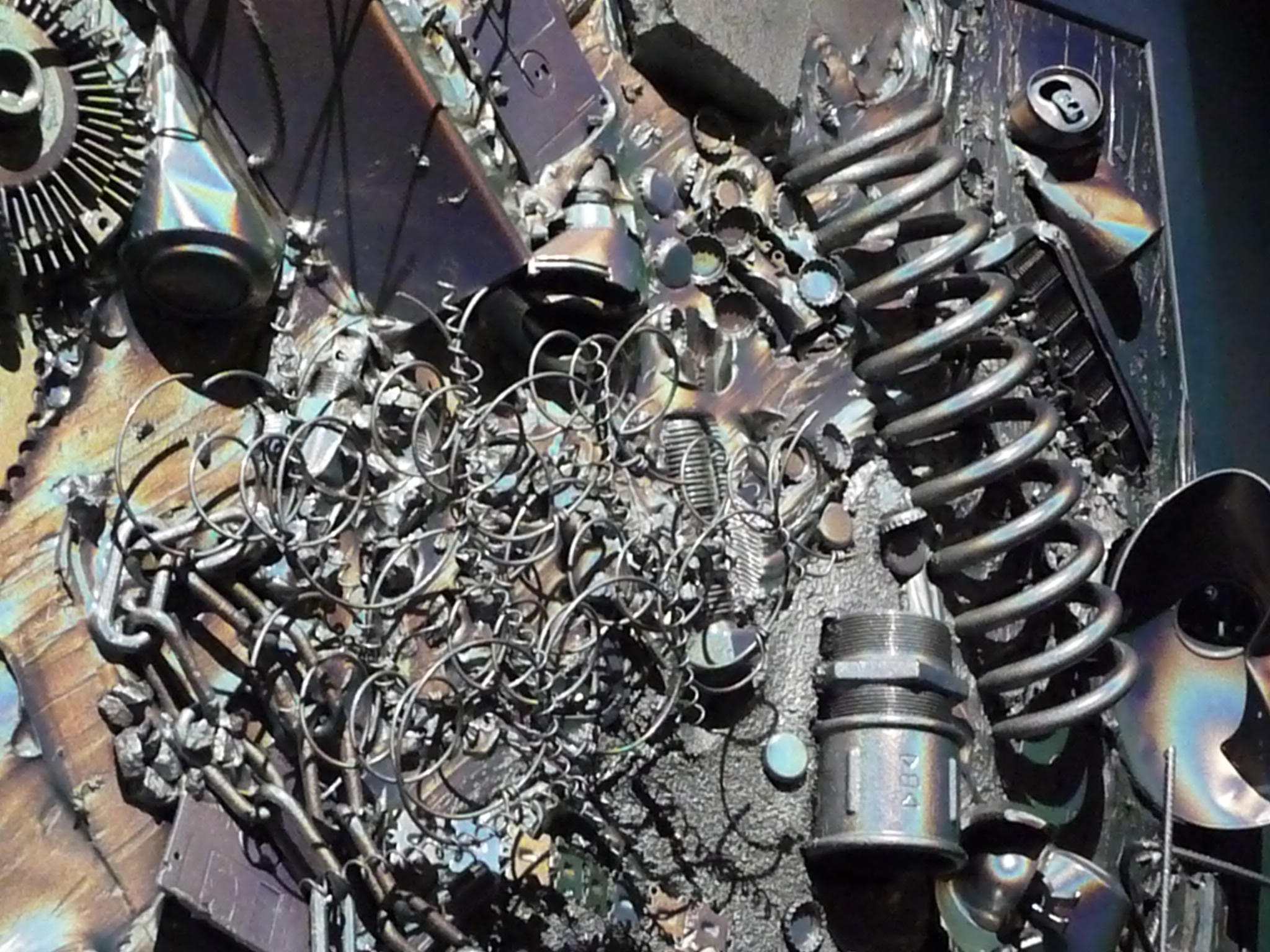

On the back wall another assortment of metal pieces--a generator fan wheel, a heavy car suspension spring, stretched bed springs, multiple nuts and bolts--again recast in black bronze and lacquered--form a sculptural painting that seems to dance between Dali-esque surrealism and your car mechanics junk box.

Probably most distasteful to those who search for good taste are two over-sized "paint by number pieces" (who didn't get a paint-by-number kit in grade school?) in which a quarter of the color zones are numbered but empty, unpainted, while other elements are made of pieces of mirror and uncertain textures. Why the un-numbered elements? "It's open--as modern art should be. The unpainted shapes allow viewers to imagine how to finish the work. The painting should find its own theme but leave room for the viewer to be engaged--just as the impressionists allowed color to dissolve into something else [depending upon how close the viewer's eye was to the canvas]."

Anselm Reyle readily acknowledges that his work, including all its visual games and gests of irony, isn't for everybody. A show in Japan was a hit. Another in India, where the underlying images and the stories attached to them weren't known all fell flat. "It didn't work at all," he said with a shrug. Then he added, "But with kids who have no idea of abstract art, everything is open and they seem to like it."