Sometimes a nail is just a nail. But what if a drill is really a pencil? And what is it that makes a pencil draw?

Yazid Oulab, who grew up in Algiers with family in Marseille was full of these musings when he was a child, and he hasn't let them go. Until he was 22 he worked alongside his dad as a car mechanic. Metal fascinated him. Words too fascinated him when as a boy his mother tried to teach him to read.

"I was a slow learner at first," he said during a conversation at the FRAC contemporary art museum this summer in Marseille. What I loved was staring at the letters, their forms." He especially loved the shape of the letter "W." It's plunging double lines, bouncing back on two sharp peaks and the open triangular spaces inside. "Eventually," he smiles, I caught up with the other students, but I was more interested in the art of making lines that contained the words and their meanings inside them."

When you know that little fragment of Yazid Oulab's personal history, it changes how you see his drawings and sculptures.

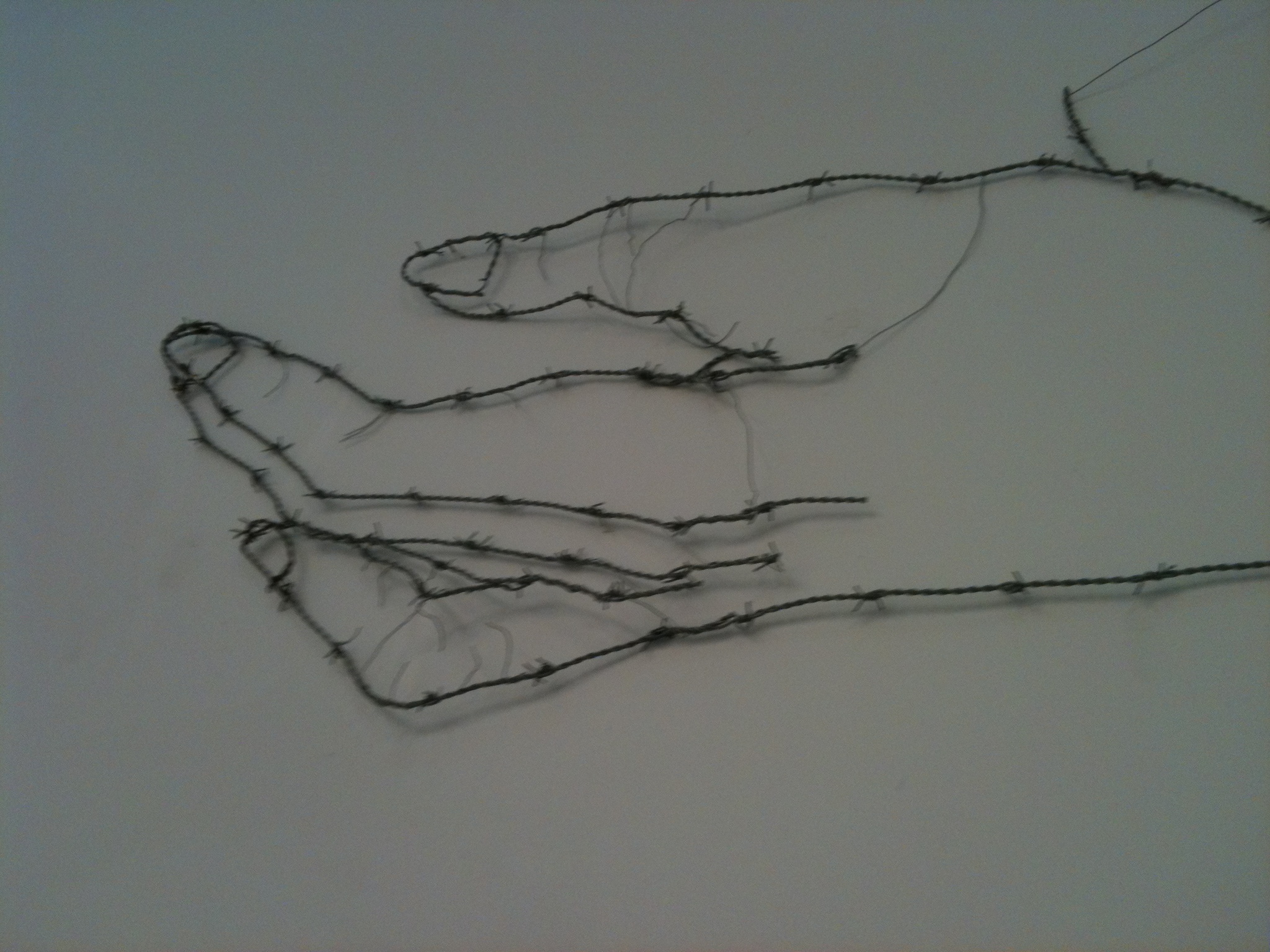

But should it? The formal argument has long been that the art should stand on its own long after the artist has disappeared from the earth. The work is the work. If the artist, in this case Yazid Oulab has shown us a new way to see a molded strand of barbed wire or the grace of a simple nail, why should we demand more?

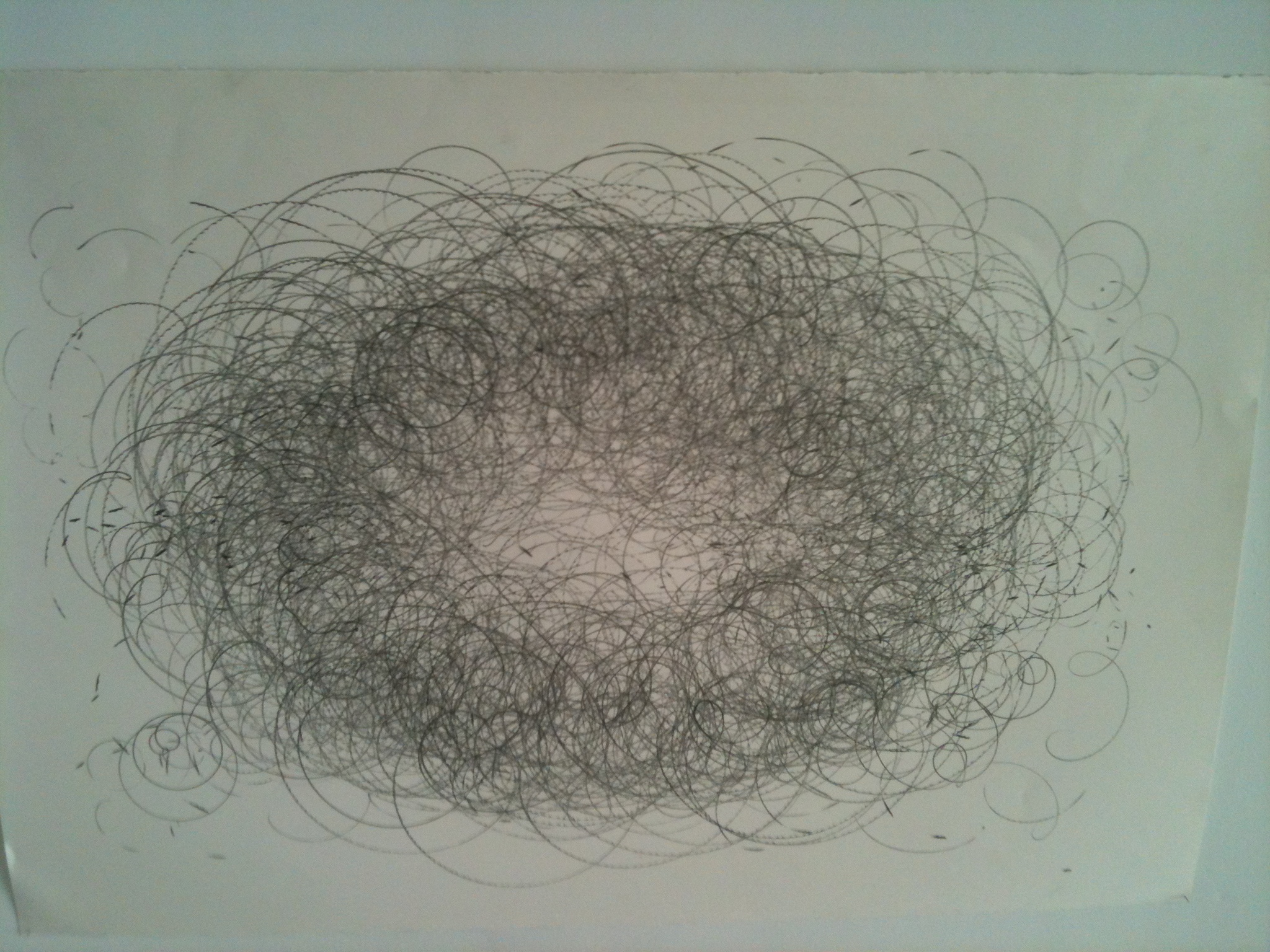

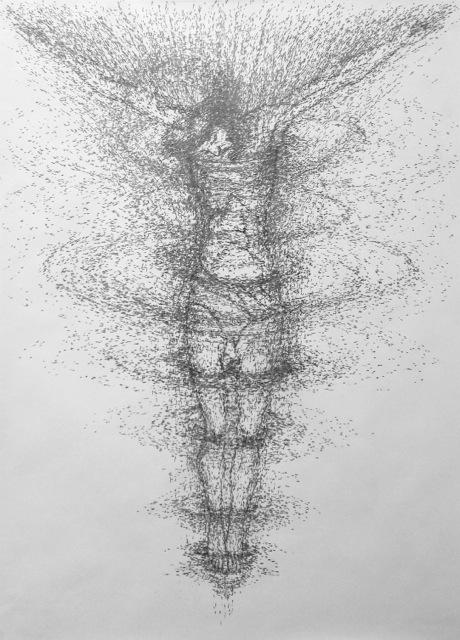

We now interpret Van Gogh's blastingly chaotic forms and colors both in relation to his time and to his personal psychic history, and as we see Picasso in relation to war and Spanish fascism. Might we not see the nest or the crucifix drawn by Yazid Oulab, a Sufi Muslim (more or less, he says), using a point of graphite mounted on a mechanic's drill in the context of his/our time and his life? If Picasso could not be separated from his own strain of Marxological psychoanalysis, contemporary art more and more demands that we enter into the mediatized -- or anti-mediatized -- experience of the artist at work, in Oulab's case in the shabby surroundings of small metal and craft shops in the center of Marseille where he maintains his atelier.

He wants us to sense his own excitement at seeing a nail upside down as all the things it might be: the Alif or first letter of the Arabic and several other Semitic alphabets, or a crucifix (which aside from being a Christian icon was long a sacrificial instrument shared by Jews and Muslims), or a tool that holds an apparatus or even a life together. A knife fashioned of soft graphite speaks at once of the mined carbon allotrope, which is itself a less dense cousin of the same carbon that under immense pressure sparkles as a diamond. A pile of graphite dust positioned next to one of his multiple graphite objects speaks to he source of writing, of all literature, but it might just as easily recall that the the enormous sparkling, silvered nails stacked across the room once existed as bits of earth before houses and bridges and Eiffel Towers had been invented or dreamed of.

When Oublab's school teacher mother became so exasperated with her son that she tapped him on the head with her teaching slate. Eventually, when he failed the national high school graduation exam she turned him over to his uncle Yazine, exclaiming, "He only knows how to draw and dream!"

"Quit worrying," the uncle answered her. "Turn him over to me." That branch of the family turned out to be just as full of dreams and tale telling as the young man, who soon enough passed the entry exam for Algiers School of Fine Arts, from which he later transferred to the Marseille School of Fine Arts -- even as he earned his keep working on motors in his father's car shop.

All that is some decades past. Now you can find Yazid Oulab's graphic and sculptural dreamworks in contemporary art museums and galleries all over Europe -- most extensively this summer at the FRAC Museum in Marseille or at the Galerie Eric Dupont in Paris.

Photo Credit: Galerie Eric Dupont, Paris

Meanwhile should you pass through Marseille during its celebration this year as Europe's Culture Capital, it would be criminal to miss a diversionary sunset stroll along the restored dike at the opening to the old harbor where Mediterranean bound ferries pass regularly. There the installation of white stairs and stone blocks by another artist-sculptor, Kader Attia, captures the sublime, soft rose light that has forever been Marseille's signature.