It's not every day that you find Christian pilgrim's shoes celebrated on Muslim prayer rugs - or Christians, Hassiduc and Muslim travelers gathered together to break bread. Less and less, it would seem in this current era of fundamentalist blood letting. Unless you stumble by one of the most beautiful and remarkable museums of contemporary Europe, the MuCEM set on the Mediterranean waterfront of Marseille

The current--and daring--exposition, "Shared Sacred Sites" documents in photographs, sculpture, paintings (historic and contemporary), news clippings and objects from all across North Africa where the three great monotheist religions have shared the same spots, buildings and sometimes even prayers--despite recurrent campaigns by certain Christians and Moslems to eliminate any they consider infidels from the face of the earth.

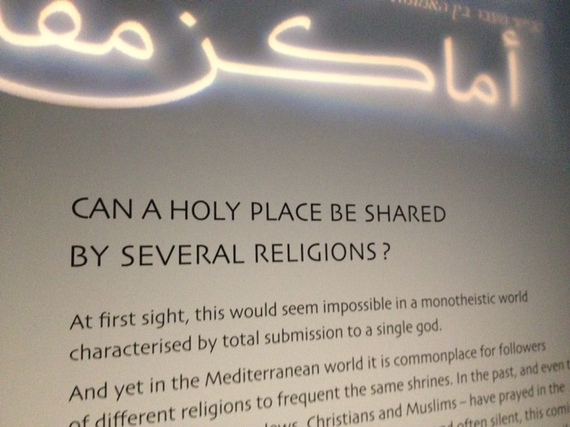

As the opening panel--presented in French and English but not Arabic or Hebrew--asks:

Certainly not, if you ask the demonical murderers of the Catholic Inquisitions and Islamist Jihad, but earlier and elsewhere, yes, in sanctuaries ranging from Morocco to Turkey. All three traditions, as the multi-media installation at the MuCEM illustrate, shared not only the original saints of what Christians call the Old Testament, most notably Abraham, rendered in cut plaster by the 20th century sculptor Mordecai Perelman. For the Jews Abraham was the great pilgrim father, though he is equally claimed by Christians and Moslems as both a patriarch and as a sacred symbol of the obligation to welcome foreign travelers.

Pilgrimage, at once physical and spiritual, is a central themes of the MuCEM exposition, represented movingly by a prayer rug created by the Franco-Algerian Naji Kamouche, on which multi-lingual and multi-colored shoes of travelers rest.

One of the most startling presentations, however comes in a room identified as "Mary the Christian, Mary the Muslim." Tunisian calligrapher (and French resident) Abdallah Akar has created a series of vertical boards bearing passages from the Qur'an in praise of Mary, one of Islam's most important saints whom Christians call the "mother of God." Nearby, an entire wall is covered with newspaper clippings in Arabic, reporting the surge of Mary "sightings" in Egypt following the 1967 Arab-Israeli war.

It is here in the depictions and stories of Mary the Universal Mother, that serious questions arise for those who do not subscribe to any of these monotheistic myths and who indeed often see monotheism as a force used to justify mass murder. A surge in Mary sightings erupted in Egypt in the 1960s, we are told, mostly reported by Muslims after the Arab-Israeli war. An entire wall is covered with yellowing newspaper clippings reporting the Mary sightings.

When I asked ethnologist and curator Manoel Pénicaud how he distinguishes beliefs and myths, he cited the legend of "the seven sleepers" common to both Muslims and Christians, represented in the show as a set of vertical glass panes covered by calligraphy. "Myth," Pénicaud said, "is how writers or artists, often outside the religion, refer to religious stories. He cited another installation, a contemporary statue of St. George and the Dragon, a holy figure important especially in Palestine to both Christians and Muslims.

But wouldn't the "sightings" or "appearances" of Mary in Egypt, strike most of us as the territory of myth and legend? He smiled and answered, "Our job (as ethnologists) is not to say whether something is an invention or reality. Our function as researchers is to observe social phenomena."

Perhaps comparably shocking to many is the Ste. Catharine Monastery in Egypt where Christians have been baking and sharing bread with Bedouins since before they converted to Islam in the 7th century.

What sets the expositions at the MuCEM apart from many others is the MuCEM's close engagement with both art and ethnology in its physical context, set as it is on the shore of the Mediterranean sea where this spring at least 1,800 people perished fleeing war in Syria, Libya and other African lands, largely a result of military meddling by European nations and the United States. The exhibits in this new museum--opened only two years ago--avoid touching directly on contemporary catastrophes, but some of the references are inescapable, as in "the Holy Family's Escape by boat from Egypt.

If there is a "political" message to this summer long program, it is that multiple myths--or religions--even when they are passionately adopted need not end in beheadings or autodafés. There do and have always existed sanctuaries where pilgrims from many places break bread together.

All photos by Frank Browning