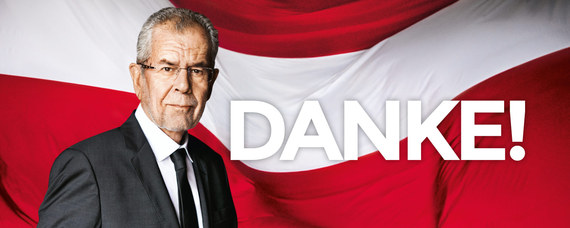

The country I was born in and the country where I live -- Austria and the United States -- went to the polls in November and December to elect new heads of states respectively. Alexander van der Bellen, competing for a largely ceremonial role, and Donald Trump, the designated leader of the free world, won presidential elections in their countries by running very different campaigns. The former canvassed on a pro-European Union agenda, pluralism and tolerance, the latter, like van der Bellen's challenger, Norbert Hofer, ran a platform fronted with anti-immigration, anti-globalization, anti-elitist slogans, underlined by the populist idea that it is time for voters to finally take their "countries back" from the out of touch political and business elites. As someone who spent half his life in Austria and the other half in the United States, I have often found myself having to defend the former's politics in the U.S. and the latter's policies in Europe. It goes without saying that this has not been an easy task of late. Both countries appear to have embraced ideologies operating outside the post-World War II politically correct consensus. After all, the far-right presidential candidate of the Freedom Party, Norbert Hofer, won over 45 percent of the popular vote yesterday. The aggrieved Archie Bunkers of the world appear to be on winning side of history, although their advance was temporarily stalled in Austria on December 4. The popularity of politicians like Hofer and Trump feed into an overall narrative of a collapsing Western liberal order on both sides of the Atlantic, a return to nativist politics pitting "Us" against "Them," and ultimately forces us to for the first time since 1945 to confront fundamental questions of the essence of democratic government--and perhaps more importantly -- central questions about who we are as citizens of Western democracies. For example, is our democratic identify as Austrians and Americans largely defined by the anti-establishment message and the rejection of pluralism and tolerance? I think not, and this not just because of the victory of Alexander van der Bellen. From my experience with both Austrians and Americans over the past 16 years, the real strengths of our democratic identity in both countries remains what George Orwell called "common decency" -- a belief in common sense virtues and acts, perhaps best summed up in a simple Orwellian rule: "Don't hit a man when he's down." Living in a democracy underpinned by human rights and the rule of law, we have an innate understanding -- akin to a gentleman's code of honor based on a sense of fair play--about what is right and wrong under certain circumstances. (Orwell also referred to it as the "the emotion of a middle-class man"). It is the foundation of civilized debate in a democracy, although sometimes anger and indignation cause us to ignore the tacit limits of public behavior. Looking back at my life in Austria and the United States, it was connected by the thread of common decency rather than the anger and fear stoked by Hofer and Trump. My high school years in the United States coincided with the right-wing Freedom Party (Hofer's party) forming a coalition government with the conservative People's Party. People even across the Atlantic were enraged. I remember the high school librarian of Fryeburg Academy in Maine, a nice Jewish lady, handing me in horror newspaper clippings of the then leader of the party, Joerg Haider, citing his praise for the SS and the Third Reich. Nonetheless, the formation of the coalition government led to massive protests in Austria. Hundreds of thousands marched in the streets of Vienna. The European Union imposed political sanctions on Austria fearing an assault on democracy and human rights with the Freedom Party in power, and Austria's president coerced the new chancellor and Joerg Haider to sign a pledge to support the core values of European democracy. Under intense public scrutiny the FPOE, rather than a wolf in sheep's clothing was tamed by the public and then Chancellor Wolfgang Schuessel of Austria's People's Party and ultimately self-destructed playing a marginal role in the coalition government from 2000-2007. Austria and its democracy survived and common decency prevailed. Common decency also ended up prevailing following the deadliest terror attacks on the U.S. in its history. On September 11, I was in the dorm of an American University in Vienna as the towers came crashing down. My first feeling -- shared by so many other Europeans at the time -- was one of solidarity with the United States. The second feeling came later emerging from a consensus among many people in both the United States and Europe that the Bush administration's response to the terror attack (invasion of Iraq, torture, Guantanamo Bay etc.) was contrary to what common decency on either continent prescribes. "This is not what we stand for," was the often-heard refrain among Americans in Vienna at the time. After all it was American troops who helped solidify democratic values in Austria after the Second World War. There still persisted a feeling of the innate "goodness" of America in Austria and Germany. (Anti-American and Pro-Russian sentiments were prevalent in both countries at the same time.) But, even today under Donald Trump, there appears to be little chance that torture will make its comeback as in the heyday of the American extraordinary rendition program. Fast forward a decade, during the 2015 refugee wave, Austrians' first reaction was that it was the decent thing to do to help refugees from war torn countries and welcome them into our land. Safety concerns paired with xenophobia may have swayed people in the other direction in the months afterwards, but there was never a question what common decency demanded in the summer of 2015. Whether it is feasible to integrate this large influx of foreigners into Austrian society remains a different question and one still to be answered across all of Europe. What unites Austria and the United States is a belief in democracy and human rights. Both nations, through their constitutions, support the four freedoms articulated by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1941: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. This is not mere Norman Rockwell sentimentality. It is the foundation upon which we can fight our more specialized political battles whether they deal with identify or class. And while the two countries I call my home have fomented populist backlashes fueled by anger and fear that could potentially undermine what I refer to as common decency, we should not forget that this is not what defines us as citizens of a democracy.

Austria's Presidential Elections And 'Common Decency'

As someone who spent half his life in Austria and the other half in the United States, I have often found myself having to defend the former's politics in the U.S. and the latter's policies in Europe.

This post was published on the now-closed HuffPost Contributor platform. Contributors control their own work and posted freely to our site. If you need to flag this entry as abusive, send us an email.