On Saturday, March 19, the world learned that China became the #1 earner in fine art auction revenue for the year 2010. It was the first year since the end of World War II that the US or the UK hadn't earned the top spot. And though Andy Warhol was the #1 selling artist for the year, 2010 also turned out to be the first year to see four Chinese artists ranked among the top ten global auction earners. (In 2009, when China ranked third, there was only one Chinese artist among the top ten).

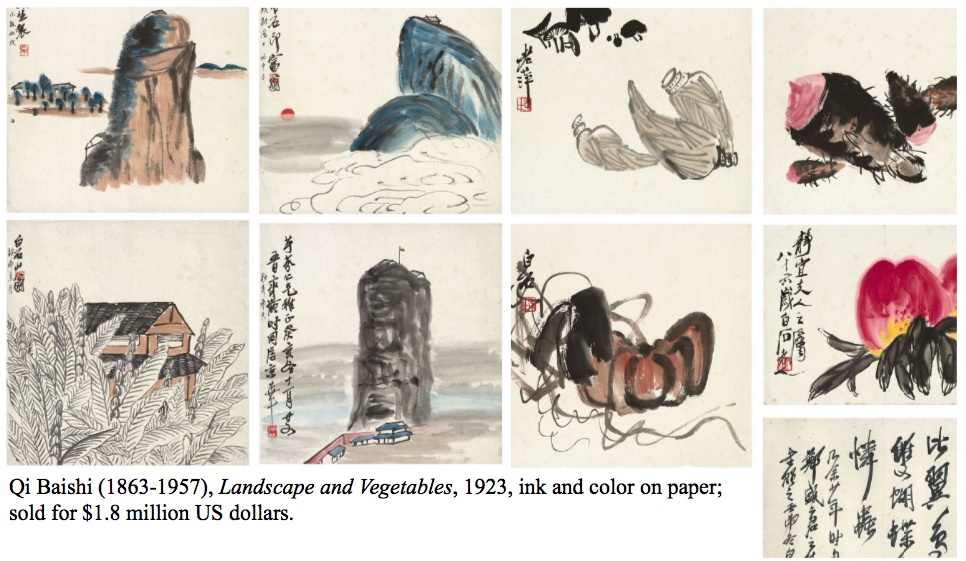

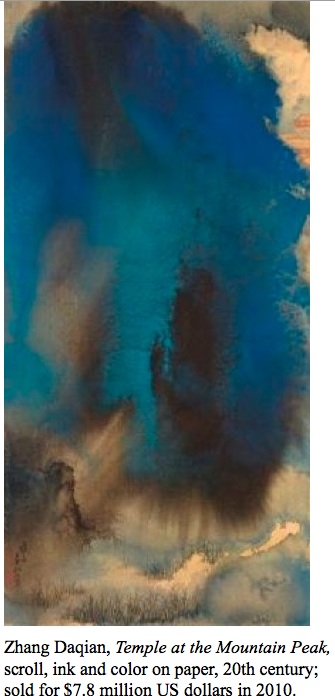

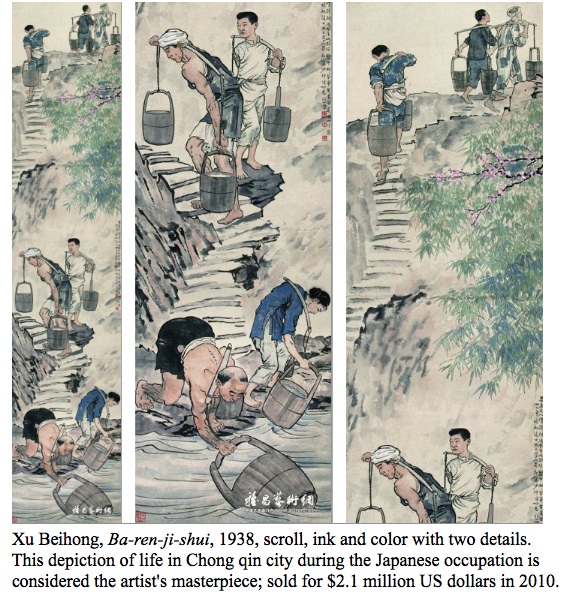

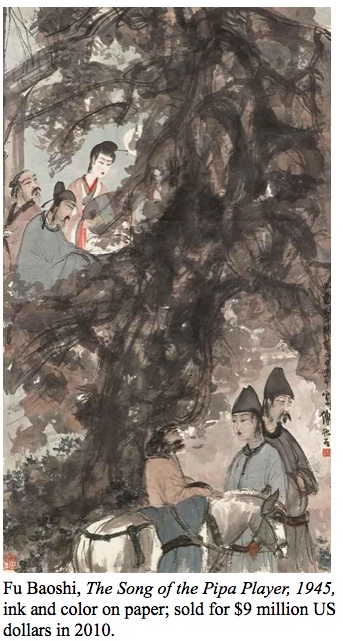

Qi Baishi (1864-1957), probably the most popular 20th-century painter in China, and the artist the Communist government under Mao Tse-Tung hailed as the 'People's Artist,' ranked #2; Zhang Daqian (1899-1983) came in at #3; Xu Beihong (1895-1953) #6; and Fu Baoshi (1904-1956) #9. No tallies were disclosed for Warhol, Qi, or Zhang, but Xu is known to have generated a total of 176 million US dollars in sales and Fu 112 million. Thierry Ehrmann, founder and CEO of Artprice.com, which released the news, added that not only are more than half of the 2010 global Top 10 Contemporary Artists Chinese, only three, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jeff Koons, and Richard Prince, are Americans.

Thierry went so far as to proclaim, "the heart of the market now beats in Beijing, Hong Kong and Shanghai, the new driving hubs of the global art market," a relocation that Thierry said "represents a turning point in the history of the global art market." It should be instructive to Western governments, particularly the US in this time when Republicans in Congress would like to gut the National Endowment for the Arts, that China's art market has benefited from the support of its government, which sees China's cultural investments to be a patriotic act.

It was not disclosed what countries the buyers of Chinese art hail from, but if we can trust recent studies of global art markets, it's most likely the buyers are Chinese. For the better part of two decades, capital has been shifting from the old centers of North America and Europe to what formerly had been called the Third World. James Goodwin, a writer well known for his articles on art collecting and investment for The Economist, and the Financial Times, and who is currently the Art Business Course Leader at Christie's Auction House, has noted that the shift away from the West has stimulated interest in the art indigenous to the new financial centers of Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Pacific Asia. In the much esteemed book The International Art Markets: The Essential Guide for Collectors and Investors, compiled and edited by Goodwin and published in 2008 just before the global economic crisis, Goodwin noted that newly affluent art collectors saw in their own culture's art the iconography promotive of a new historical yet vital national identity and pride. Naturally the Chinese, with both the greatest influx of capital in the world and the most ancient and unbroken legacy of artistic innovation and collection, would acquire and invest in Chinese art before endeavoring to collect art of the West or other regions.

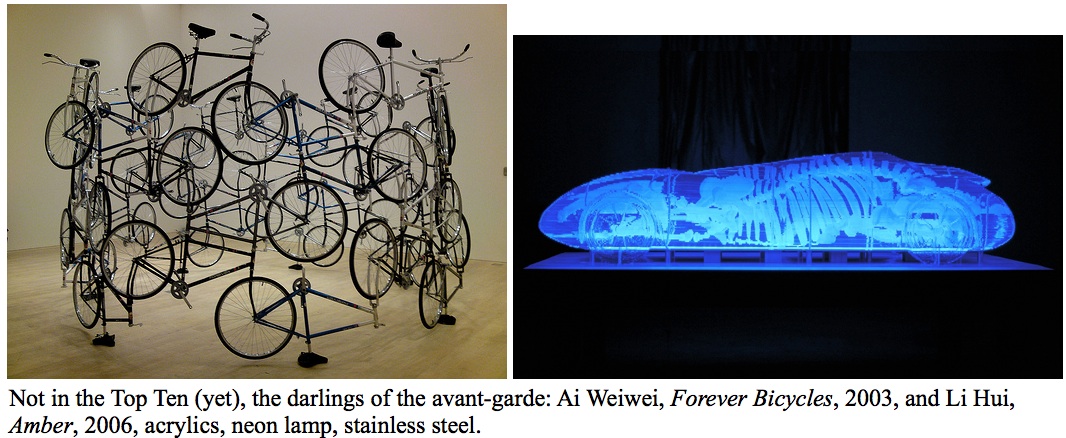

What does this mean in terms of the shifting global importance of artists and cultures specifically, and to the future of art in general? It seems only natural that China's dominance and self-interests in the market will embolden the efforts of China's art critics and historians to reshape the canon of global art history to better reflect their own image--at least in focusing more world attention on the artists who continue the long line of traditional Chinese genres and subjects. Less certain is what this shift means to China's flourishing avant-garde, which includes a number of renowned Chinese conceptual artists, notably the dissident Ai Weiwei and the relative newcomer Li Hui, who have generated considerable critical approbation if not record-breaking revenues. We know only that it's long been a truism of war as well as economic superiority that to the victors (or to the top earners) go the honor (or at least the expectation) of narrating history.

We've seen in recent decades what the opening of the market floodgate means to the nations whose artists redefine the boundaries of art, but few can recall a time when the floodtide swept an entire national culture to the pinnacle from which aesthetic and social adjustments can be issued to the rest of the world. In China's case, at least if we consider the top earning Chinese artists named here, the artists signify that the Western predilection for the new and trangressive art that has dominated the art market and art history for the last two centuries might face their eclipse by a culture still favoring artistic traditions. Could the shift in markets translate to more traditional contemporary Chinese artists--and possibly even more traditional Western artists, growing in esteem? That is, receiving more representation in museums, feature articles in trade publications, and internationally distributed monographs-in-translation--at the expense of the artists who represent what's left of an increasingly threadbare avant-garde? The challenge that Western curators face is how to assimilate artists who appear traditional in relationship to the Western post-postmodern-garde without falling back on eurocentric values that once marginalized non-Western art as "ethnic," "regional" and "traditonal." It's unlikely that such prominent art will be resisited or marginalized by Western culturophiles. The North American and European markets for traditional Chinese art have long thrived. All of which can only mean that to satisfy tastes for both the traditional and the avant-garde, parallel and varied art worlds will become more prominent. The pluralism that has flourished since the 1970s may seem miniscule compared to what the international markets will promote as more and more indigenous art currents to the mainstream.

With the West losing it's stranglehold on the markets, the scenario of a single nation dominating global art history, and certainly real cultural production, will likely have little currency considering that nations beside China are striving to expand their indigenous cultural production and introducing it to a nomadic tribe of art cognoscenti flying to and from every global center hosting a biennial or art fair. China, after all, isn't the only nation to see it's net worth grow. It's true that according to the 2010 World Wealth Report, the number of "ultra high net worth individuals" (UHNWIs, or millionaires and billionaires) in Pacific Asian nations surpassed Europe's for the first time in 2009. But the number of UHNWIs in Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East, along with those in the US, also continue to grow despite the economic setbacks of 2008. The world has simply become too diverse and too interdependent economically, culturally, and geopolitically to defer to any one central canon of culture and history imposed on it.

For that matter, Western aesthetic values never truly filtered down to the streets of non-Western cultures, despite the domination of Western aesthetics and artists over world auction records. The cultural shift may startle Americans and Europeans who slept in the insulation of their dominance, but the dealers and collectors aware that art knows no borders have been keenly alert to the artists who, for at least the last two decades, have been sending out the roots of crosscultural exchange necessary to forming an expanding, interdependent, and symbiotic global network. Vital and "new" international art markets emerged in the last decade in Deli, Tehran, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai, to join with markets not much older in Hong Kong, Taipei, Istanbul, Caracas, Mexico City, and Tel Aviv--where worldwide sales of art are rallying record highs. Although the stability of these markets has yet to be established, especially considering the devasting breakdowns that 2008 brought, when seen against the backdrop of the greater international market, the art world offers more than record gains on investment. Under such circumstances, it's unlikely that only a few world powers will dominate the global art markets. The reality is that capital is spreading throughout the world at unsurpassed rates. But ahead of capital by far spreads the desire for indigenous cultural renaissance.

It was only three short years ago that James Goodwin proudly announced that his book, The International Art Markets, was the product of correspondents reporting from 21 countries in Europe, 12 countries from Asia and Australia, 5 from South America, 4 from the Middle East and Africa, and 2 from North America. It was the first time that a published international survey of art markets gave each country equal opportunity to present its art market, despite that the global market in 2006 was still over 70% weighted in value by the United States (45.9 per cent) and Britain in 2006. Such a level playing field was intended by Goodwin to be non-judgmental, as he expressed that any of the world markets could at any point in the future develop exponentially, what with the economic laws of comparative advantage "working to the benefit of those markets seemingly at the bottom of the pile." Indeed, as other countries develop, Goodwin seemed to predict that the art market will be redistributed more evenly on a larger scale around the world, based on knowledge, wealth, the competing intermediaries who promote and sell art, and above all, artistic talent.

The performance of the international art markets over the last decade gives indication that a new breed of art collector and art institution ideologically nourished by decades of cultural cross-fertilization is now ready and patient enough to invest in underappreciated local productions. Counted alongside growing institutions who favor traditional or national artists, buyers and sellers eager to make their mark on global markets have become so numerous and so voracious they are generating an economic windfall that showed resistance even to the economic recession. The steady incline in value and appeal of world art as the new "gold standard" proves idealism, at least collectively shared and widespread idealism, can and does fuel markets, especially when it also inflates the value of art and entertainment attuned to post-colonial interests.

Then, too, crossculturalism is as ancient as the trade routes. And the art-without-boundaries myth has a cherished place in the narrative of Western modernism. Who can forget the quaint accounts of small coteries of European avant-garde artists who, in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, appropriated formal elements of Japanese ukiyo-e prints and African masks in their painting and sculpture. Of course, no one can afford to forget that the history of cross-fertilization comes with a tragic world narrative following the course of empire building and genocide. Think of Islam's medieval armies sprawling from the Indian to the Atlantic Oceans depositing their geometrically interlaced ornamenture and caligraphy along routes carved out by swords. Consider the conquistadors of Christian Spain erecting polychrome crucifixes and santos over the ruins of Teotihuacan and Cuzcuo, while holding ornamented monstrances of pristine silverwork over the corpses and captives of preColumbia. Think also of the scourge of Mongol hordes cultivating the Chinese scroll painting and cloisonné, Persian minatures, Indian architecture, and Tibetan Thanka paintings they seized in the east while both arresting and prolonging the development of Byzantine iconography for centuries in the west. More recent occupations--the British in India, the Americans in Japan and Korea, the Soviets in Eastern Europe, the Europeans in Africa, the Israelis in Palestine--have generated their own cultural crosscurrents, some yet to peak, flourish, or be accepted by the (formerly- or still-) occupied populations. Oh, and yes, those African masks that Picasso so loved came by route of the slave trade, many with their association with female genital mutilation euphemistically parlayed by ethnologists and curators as "coming of age" rituals. And those figurative ukiyo-e prints (literally "of the floating world" of geisha, courtesans, prostitutes, and queer samaurai and kabuki actors) beloved by the impressionists and their ilk as often as not chronicled the last gasp of indigenous pan-sexuality that moralistic Western states demanded the Japanese purge themselves of in order to benefit from their much-needed trade.

Considering the defilements that accompanied the shifts from one past empire to the next--all the while heralding the rise and decline of newly assimilated cultures--we have by comparison mitigated the methods by which crossfertilization takes hold of and disseminates cultural innovation. Despite the isolationist and extremist war drums beating far afield from the mainstream today (say in tea party camps and al-Qaeda cells), the powerful currents of crossculturalism we witness in today's global art markets is an intricately variegated offering porously absorbing difference. Today's global agora, at least in terms of contemporary art, is more a mongrel affair than a thoroughbred race, a mix of breeds that becomes all the more impressive when the newest players are remembered as the nations once occupied by European powers who, after decades of anti-Westen posturing, today rejoin their former colonizers--this time transacting if not soon to be dictating the terms of cultural trade. While nationalist and ideological agendas still resonate in art markets around the world, the greater proliferation of world trade benefits the diversity of cultures. For what seemed until very recently to be an elite market out of sync with the cultural diversity, populist fixation, and ideological pluralism of the art and artists it promotes finally revealed itself as accounting for the current drive to globalize the disparate art markets.

What seems certain is that this new global shift--or perhaps it is really more a dispersal and diversification of cultural authority--will dictate what is the most relevant, if purportedly zeitgeist-art of an accumulating world culture that challenges all monolithic and static criteria for judging art in favor of an increasingly nomadic ideological migration from one aesthetic and cultural model to the next. The increasing demand to experience art made around the world has driven critics, curators, and collectors to adapt to the diversity of the new international markets by leaving behind the old impediments of ethnocentric values. With cultures converging and colliding, old insularities no longer buffer or mediate cultural exchange. Old oppositions like "Chinese classical art" and "Chinese modern and contemporary art" make less and less sense as the boundaries between the two become more and more porous, more and more fused and syncretic.

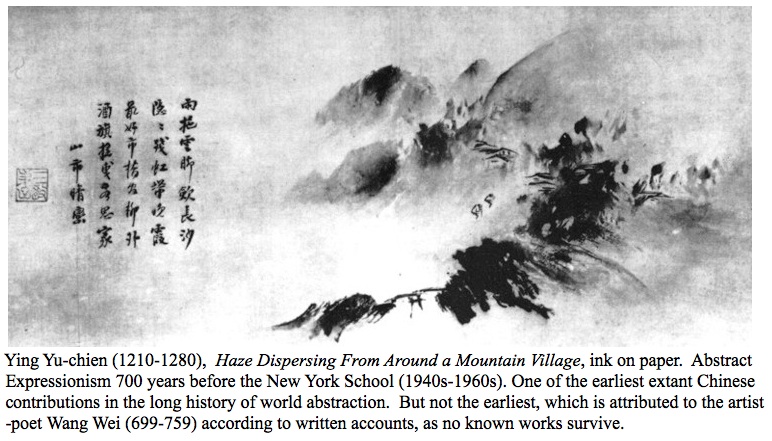

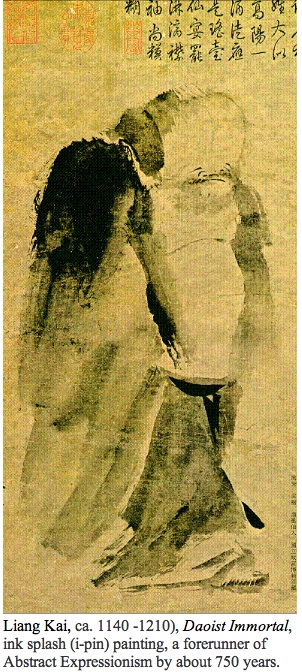

Perhaps the biggest challenge comes when the experts in Chinese classical art sit down with the experts in American painterly modernism to hash out their discreetly entwined artistic legacies still much in denial by both camps. Most difficult of all will be the re-demarcation of the part of American 20th-century painting that is derived from 8th-to-15th century Chinese painting. As a result of a great deception by some American modernist critics and artists of the first half of the 20th century, and the blithe yet ethnocentric ignorance of many others to follow them, it is foresseable that the outcome of this debate and realignment of histories will dismay American culturophiles. For it may yet turn out that with the new Chinese leveage swaying minds, art history may yet be rewritten to reconceptualize the American and European Abstract Expressionists as in fact a very late, and often derivative branch, of classical Chinese painting.

To read more about the Chinese origins of abstract expressionist painting, download my 1999 Art In America article on artist Pat Steir, and begin reading at the end of page 116.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.