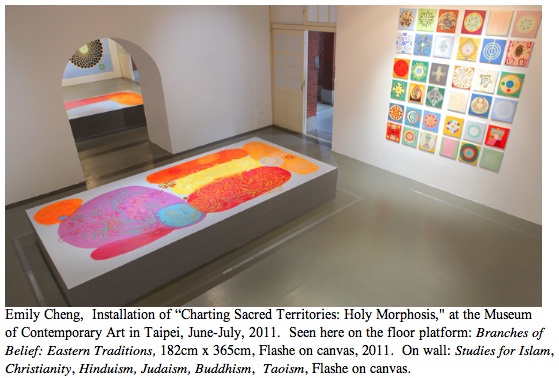

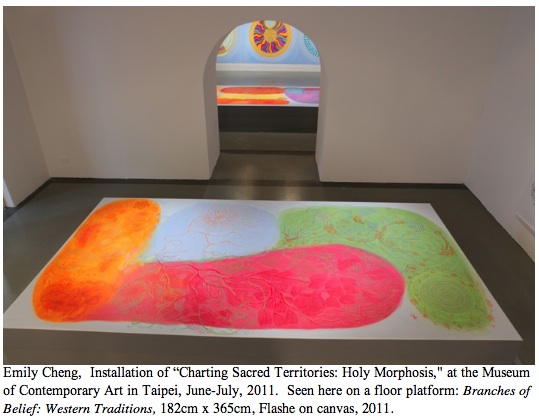

New York artist Emily Cheng attempts to reconcile the traditionally oppositional modes of science and faith in two concurrent solo exhibitions of conceptual paintings and drawings. At The Museum of Contemporary Art in Taipei, Cheng presents Charting Sacred Territories: Holy Morphosis, June 17 through July 17. Meanwhile, at Hong Kong's Hanart TZ Gallery, Cheng has installed Meanders and Morphosis: Charting the Nature of Interior Spaces, on view July 7 through 30.

It's not at all certain whether Cheng has succeeded in her attempts to reconcile the wisdoms of religion and spiritualism with the knowledge of anthropological science and rationalism she uses to chart their relationships. Just as daunting is judging whether Cheng's paintings and drawings successfully conflate the artistic conceptualism that informs her work with the vibrantly painted forms through which her conceptualism is realized. To add to this complexity, the exhibition in Taipei takes a diagrammatic and taxonomical approach to representing and distinguishing the great array of human difference underpinning our consciousness and cognition in general and religious and spiritualist ideologies in particular. The Hong Kong show, on the other hand, deliquesces difference altogether by blending the distinguishing features of traditional religious signage and symbolism into a visually theatrical "oneness" or plenum from which all creation is imagined to emanate and recede. Taken together the two shows, particularly the paintings, make for an exhilarating visual and conceptual experience and contemplation of the human proclivity for invention in terms of metaphysical, theological and ethical teachings and their expressions in the objects and ideas of artistic practice throughout global history. The two shows are also perfectly suited to the new breed of cultural nomad eager to travel the world in pursuit of the diverse experience of the world's emergent contemporary cultural and artistic hybrids.

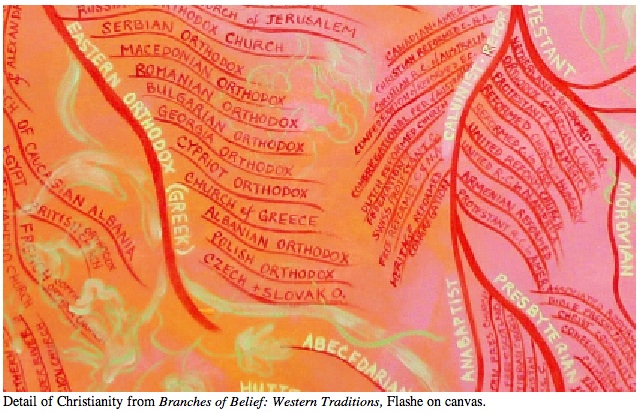

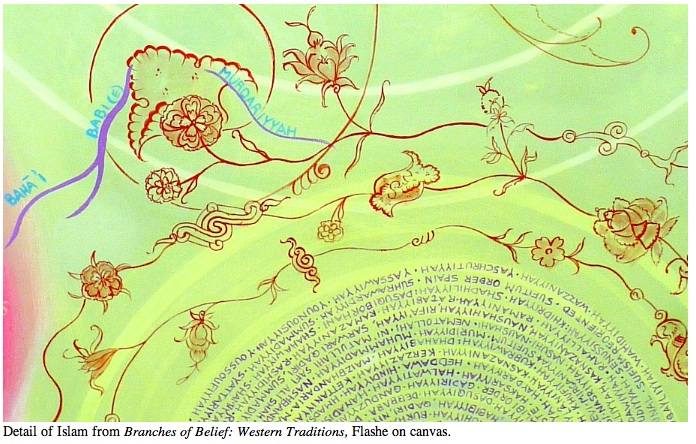

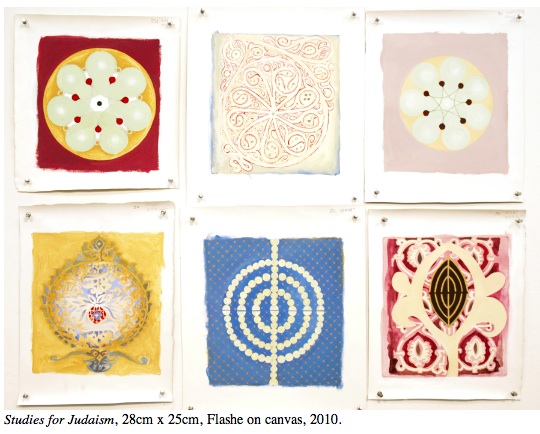

On the surface, Cheng's Tapei exhibition assumes the neutrality of an anthropological survey in its visual recording of the names, classification and diagrammatic delineation of the geographical and historical evolution and branching off of world religions. Based in part on the theological relations and differences among faiths and in part on their historical and geographical origins and geneses, a deeper consideration of the Taipei show reveals a philosophical scope that challenges at least one central bias running through and curtailing the greater art of modernity, particularly that made in the West. It's the modern secular bias that can be said to circumscribe what knowledge we believe to be truth to only that information or experience shown to be verifiable, quantitatively certain, and factually objective. All other thought, particularly that based on faith alone (such as religion or mysticism) is inveighed by this bias as poetic, empathic or something less in the hierarchy exalting science, technology, and logic over art. It's a "positivist" or "materialist" attitude that is roughly summed up by the 20th-century philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein as an estimation of the limits of our language reflecting the limits of our experience, which in turn defines the limits of our world.

To say that this limiting bias that so often constrains contemporary art ensures that the artist who broaches religion or spiritualism as the topic of her art will face controversy is an understatement. More accurately, the artist who broaches religion is more often than not marginalized--shoved clear out of the mainstream of artistic discourse--even derided. But to those who claim that after untold millennia art has finally--that is in the last century or two--escaped the confines of religious faith, I say think again. Every time we rely on such constructs as reality, culture, science, technology, government, law, science, even the ideologies surrounding sports and entertainment--for that matter surrounding any life activity, institution, authority, sexuality, family or friendship--we are also behaving religiously. At least this is the case when our belief in or affinity for customs is based on some wisdom handed down to us from authorities, schools, canons and traditions that we don't question or test for ourselves to see whether our knowledge of them is provable. Ironically, the source of our real knowledge--that gleaned from personal experience--is downplayed, made secondary to received wisdom, for its being bounded by our inability to share our most direct and personal experience with others.

It's not so much that Cheng confronts the modern devaluation of religion. In fact she seems to blithely ignore it. Yet her Taipei show is comprised of paintings and drawings that can together be considered a scientific project of charting not just unscientific faith, but the organized and institutionalized means by which we organically rejuvenate the human condition--the "body" and "soul" of societies. Her Hong Kong show, on the other hand, goes much further in contesting the authority of inherited wisdom and knowledge by presenting paintings that evidence hew own uniquely personal belief system lying outside not just science but outside all organized systems of faith as well. And yet, though her Hong Kong paintings lie outside science and institutionalized faith, they don't challenge them. In fact they seek to incorporate both science and the known religions and spiritual systems of the world into a holistic picture that has meaning as much for those of us who are of an agnostic and atheistic turn of mind yet recognize the scientific study of faith and religion, as well as the spiritualist practitioner and religious devotee.

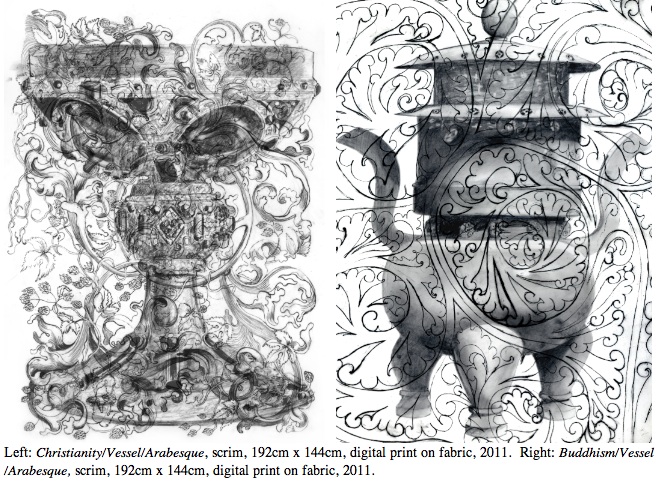

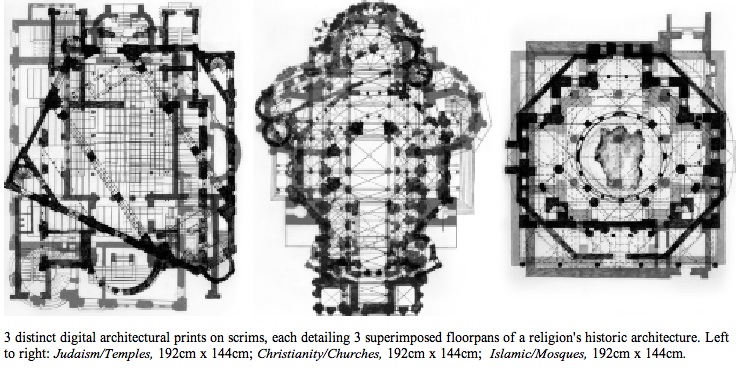

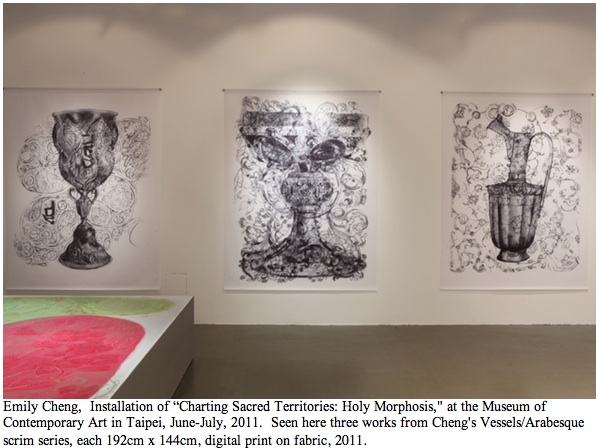

At times Cheng's project becomes a bit too literal to soar. In Taipei, for instance Cheng installed scrims overlain with drawings of architectural plans for historic mosques, cathedrals, temples, and synagogues, along with drawings of antique artifacts--chalices, pitchers, incense burners and other functional vessels that double today as the symbols of faiths. Both the architectural overlays and the vessel drawings convey to what extent the history of art and artifacts is conjoined with the greater history of mysticism, ritual and religion. And the viewer can see in these renderings the reasoning that it shouldn't strike us as exceptional or marginal to find the branching lineage of religion made the subject of art, considering that art owes its origin and existence to religion and spirituality. But unlike the paintings in both shows, the black and white renderings come off as academic and uninspired; giving too much to science and too little to art.

Part of the problem with the graphic works is that Cheng doesn't fully resolve their apparent contradiction with her project's intention of charting the "Interior Spaces" (her name for religions and spiritualism). The artifacts and architecture, after all, inhabit exterior spaces and are composed of the physical representations, signage, iconography and structures by which we identify the world's diverse faiths. Art is, after all, both physical and ideological, while spirituality is conventionally thought to be the abjuration of the physical and ideological.

Of course the apparent point of Cheng's Tapei show is that such a divide between the interior (spiritual) and exterior (physical) forms is an entirely arbitrary conjuration of the mind, and that without this divide posed, faith and science can be reconciled. In this regard Cheng's paintings better represent the principle that the physical and the ideological can be spiritual insofar as the physical and the ideological aren't allowed to become our prisons. They thusly better embody the idea that spirituality is nothing if not freedom, which is to say it is the recognition of responsibility and the release of obsession. In being imprecise (unlike the drawings that exhibit material precision), Cheng's paintings blur all signs of the interface between the physical and the spiritual. But then painting in its virtuosity and display of subjective expression has always been able to convey better than most pre-modern physical media the notion that the very opposition between the physical and spiritual is a fallacy or illusion, the product of compartmentalized thinking that is more of use to analysis than to living--or to the rejuvenation that we call spirituality.

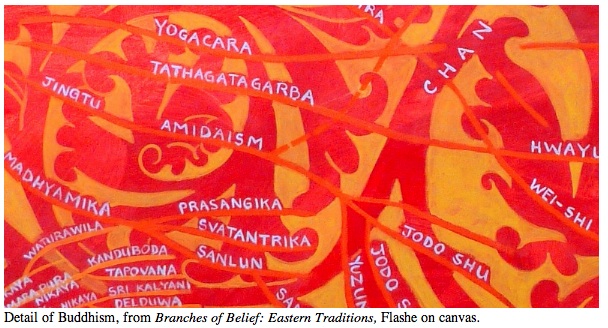

At the same time that Cheng's charts are holistic in their encyclopedic embrace of world faiths, they place stress on the differences among faiths that remain willfully, even defiantly, irreconcilable despite the new global emphasis on interfaith relations. This is where Cheng's art makes eminent use of anthropological scholarship. It's the irony of a science that seeks to reduce everything to cultural, if not physical terms, that it is required to stand in as an impartial referee for an otherwise irreconcilable convergence of world faiths. In other words, anthropological neutrality reconciles the world's faiths on a contingency basis by ironically not requiring their reconciliation--and then only by deferring such questions as what is true and who possesses truth. It's only in refusing to ask such questions in the context of her art that Cheng can claim to reconcile the existence of spiritual systems to each other and to science, if not the issues raised by the faiths, which are logically irreconcilable without human tolerance of difference.

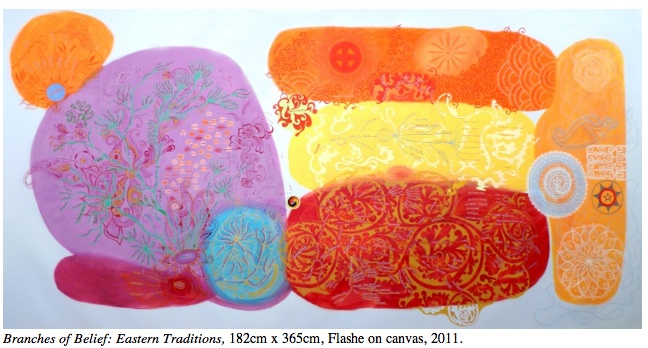

Cheng, like the anthropologist, has to relinquish any wish to unify the human cognition and expression that may or may not underpin all these different faiths. In this respect her project is a testament to the fractured nature of civilizations and cultures while making it seem near miraculous that the earth isn't beset by considerably more conflict than it is. Then, too, Cheng's branching religious trees in many instances appear to be without any clearly demarcated roots or trunks, suggesting their histories and origins are largely unknown. Unlike the family trees that geneticists have constructed by tracing human mitochondrial DNA back millions of years to a single mitochondrial-African Adam and Eve, Cheng's charts of the historic lineage of world religions can be traced back only a few millennia--or only a few centuries at most in the cases of most tribal faiths. Cheng's trees are thereby partially determined by historical demarcation and partially by the relational features of faiths.

Yet because of the vague lineage Cheng manages, a better metaphor for the religious families than "trees" might derive from the rounded, oblong contours bounded by her application of lurid Flashe colors that evoke images of overgrown melons and mangos and other large vegetation sliced open and displayed for botanical study. Meanwhile, the overall effect of the Taipei charts invites comparison with Rothko paintings, if Rothko paintings could be imagined rendered in blacklight fluorescence and carved up with branching veins with names.

Altogether more complex visually, if more conventionally expressionistic, are the Meanders and Morphosis paintings installed at Hong Kong's Hanart TZ Gallery. Here Cheng pushes her art well beyond the iconography and artifacts of visually identifiable religions, and she does so with a lyrical deliquescence of the specific signage of faiths into swirling, largely abstract but also organic mandalas that approach the painted frenzy and metaphysical idealism, if not the visual and compositional dissonance, of Kandinsky. But if the Hong Kong paintings are meant to recall mandalas, they certainly aren't the kind that intrigued Carl Jung with their symbolization of mythological pantheons and psycho-cultural archetypes. In utilizing the mandala motif, Cheng may be referring to the subtle body of individual consciousness in the same mode that Jung identifies the graphical representation of the self or the center of individual consciousness. But given that Cheng came of age in the epoch of emerging globalization and deconstruction, she might as well be interpreted as representing a new global meshing that, like some parody of a comic book or Hollywood vortex, sucks local archetypes into the swirling crucible that forms the matrix of a consciousness becoming unconscious and back to consciousness again.

This doesn't mean that Cheng's art should be confused with the New Age sentimentalism that has been born in a desire for cosmic unity. In their stark conceptualism, Cheng's paintings appear anything but sentimental or unifying. If anything, they seem to appreciate if not represent the voids in meaning, the gaps in our understanding of the world found in all faiths, systems of thought and expression, composed as they are of features at least partially submerged in an ocean of subjectivity that expands with meditation. This is why, to my mind, Cheng's Hong Kong mandalas embody the extent to which all signage (that is the various visual and linguistic languages of all knowledge) is composed with an aspect of the ineluctable subjectivity that must accompany the experience of any system of thought referring to the world.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.