The conceptual paintings of Mira Schor are on view at the Marvelli Gallery at 526 West 26th Street, 2nd floor, in Manhattan, through April 28, 2012. Visit the Marvelli Gallery website for further information. Mira Schor will also be featured at the Dallas Art Fair, April 12-15, at the CB1 Gallery booth. For information, visit the Dallas Fair website.

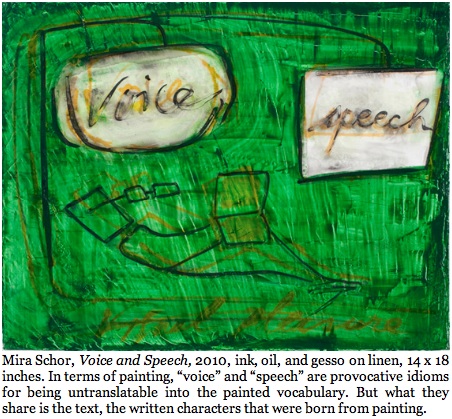

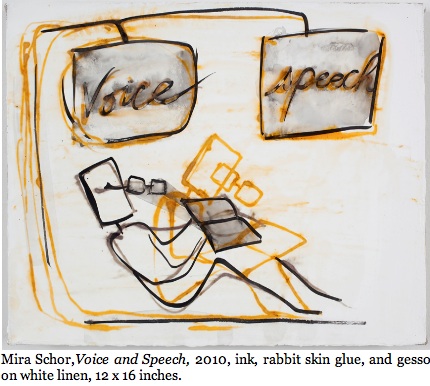

There seems to be something structurally incongruent if not absurdly wrong with an analogy between painting and the human voice, even more so between painting and speech. Comparing an instrument of sound and the collective faculty for shared, spoken language with a manipulation of visual, formal components built up into graphic signs is apt to be riddled with unbridgeable voids of difference. And yet Mira Schor, a prominent New York critic-painter for the past three decades, has made an alleged correspondence of voice, speech and painting the thematic center and motivating ethos for her latest series of paintings, all of which she has compiled under the coyly taunting title, Voice and Speech.

It turns out that Schor has ample reason for doing so in highlighting the one feature that painting, voice and speech share--her provision of remedial text pointing to the correspondences of human cognition to experience of the world. In fact, it is the text, more than the alleged correspondence that proves to be Schor's ace in an ongoing contest between painters and conceptual artists. For it is text which both regulates and perpetuates voice and speech, yet is a descendant and variation of painting.

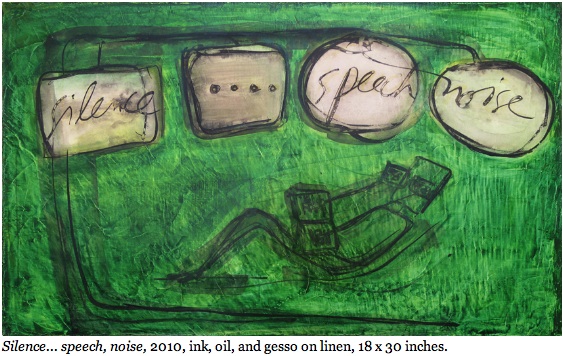

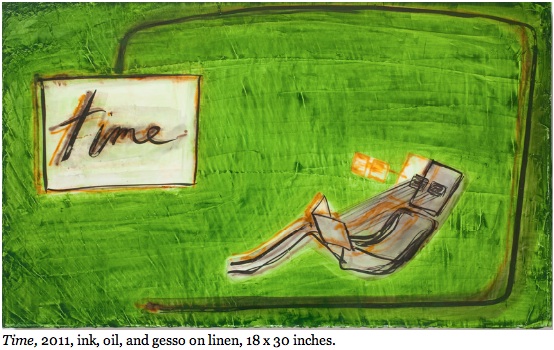

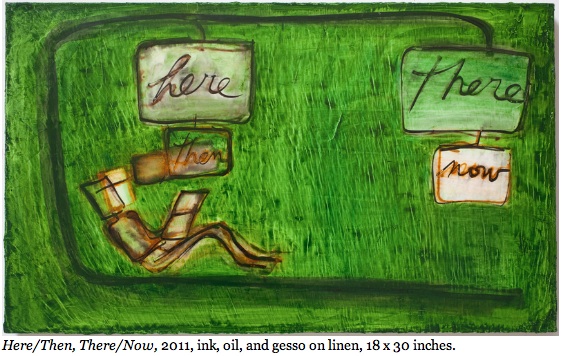

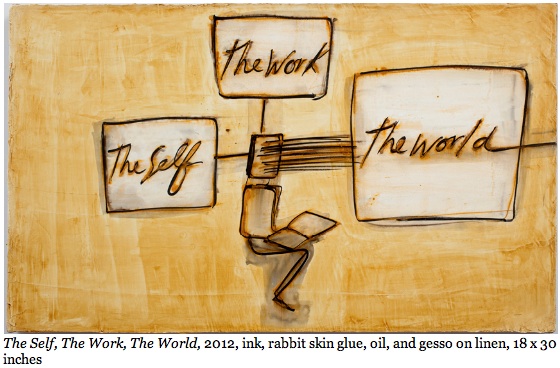

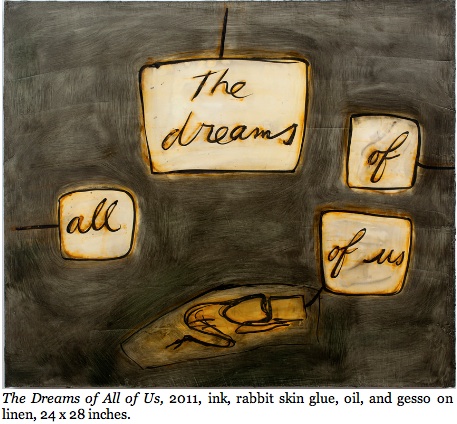

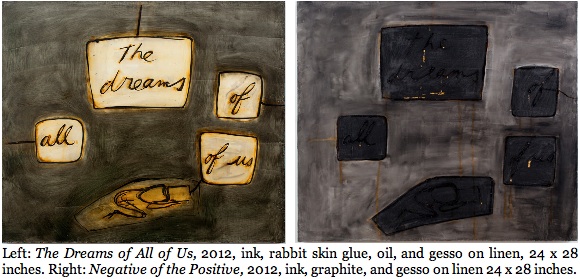

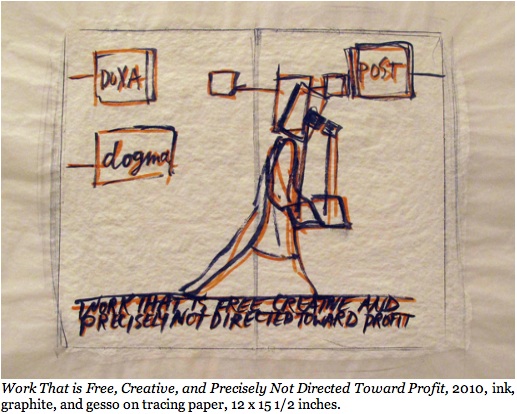

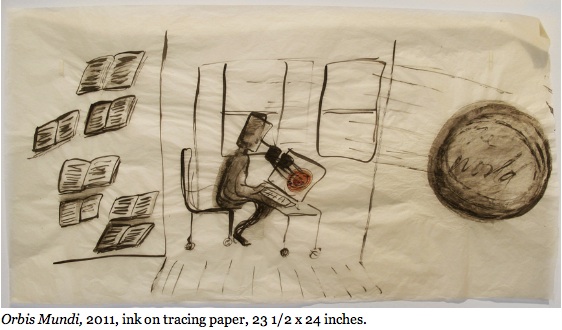

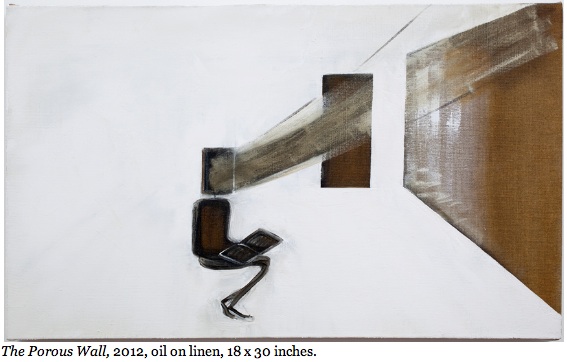

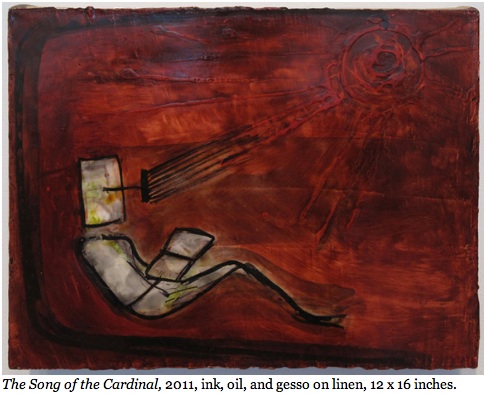

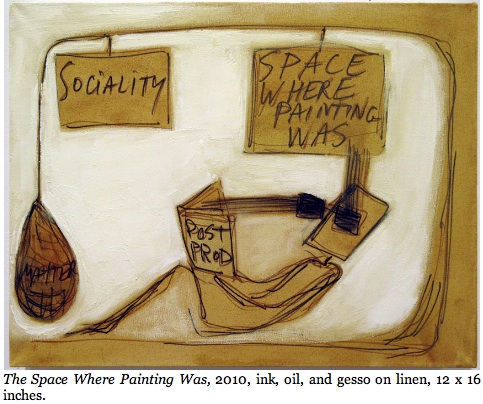

Schor has made a good deal of engaging work about the relationship of painting to writing, language and cognition, some of it featuring a recurring stick-figure avatar who could reference most any viewer of a contemplative nature, were it not for Schor's diary-like presentation convincing us that the avatar is Schor's own painted stunt double standing in for her, just as the text painted stands in for her voice. Schor's avatar is reprised for the entire Voice and Speech series, this time to live out a pleasant enough life as a scholar-painter, here representing Schor reading in a lush green garden, there contemplating reality on a radiant beach, elsewhere lying in the darkness of her room dreaming, or occasionally sitting before a computer doing what critics invariably do. The anecdotal quality of the paintings impresses us that Schor has taken on the role of narrator-theorist busily expounding on some seemingly vague theory of cognition and language. In fact, it seems to have become entirely her theory, expounded as it is now through sparsely painted surfaces, the signage that her avatar "enacts," and a sprinkling of key words that name the irreducible existential properties of experience: "the world," "the self," "work," "time," and the contextual undercurrent throughout the work imparted by the words "voice" and "speech." A viewer doesn't have to have a background in language theory, epistemology or ontology to assume such terms to be Schor's entry in the millennia-old occupation of surveying the conceptual groundwork for the bridge of our mediation between the world and our experience of it--in her case through the tenuous alliance of text, picture, and gestural markings we call painting.

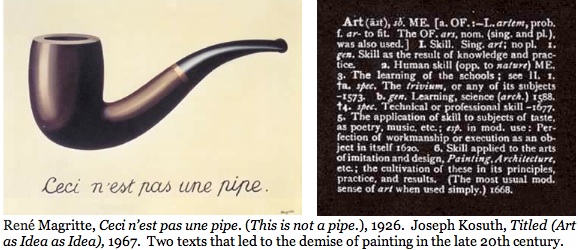

The question anyone attuned to the last century of the modernist avant-garde in art might ask at this point is, has Schor forgotten about Magritte? Rene Magritte dealt what many believed to be the 20th century's most devastating blow to trompe l'oeil painting. Every painter since Magritte who has made the relationship of the world to the painting paradigmatic of her art has had to contend with Magritte's severance of the image from its content and context before making her mark in the contemporary art world--even if s/he choses to ignore him.

Schor does anything but ignore Magritte. In fact the sparsely parsed text throughout her series of paintings is entirely "Magrittelike," both in its textual announcements of simple first principles ("the world," "the self," "time"), and by using text to connote that she is an artist who is working within the boundaries of an art world that requires painters must first come to terms with painting's cultural fatigue as a medium before they make the effort to revitalize painting as a viable and vital medium for the 21st century. It is also significant that Schor reprises the language of the very schools of modernist thought that helped to bring about the absurdly inflated myth of painting's demise and death before these schools themselves "died" at the hands of postmodern theorists. I'm referring to the reductionist epistemology that futilely sought to catalogue what we know, and the parallel school of ontology that just as futilely sought to distinguish what exists--both of which informed Magritte's iconic anti-painting that admonishes us not to confuse it with a pipe ("Ceci n'est pas une pipe." "This is not a pipe.")

Behind Magritte, Schor certainly must see the specter of Ludwig Wittgenstein hovering close by. I mean the young Wittgenstein who advanced the notion that a sentence is a picture whose truth value is determined by the closeness of its resemblance to the world it depicts. Wittgenstein became the champion of the earliest conceptual artists of the 1960s, particularly those artists such as Lawrence Weiner, Joseph Kosuth and Jenny Holzer who retreated from making pictures to confine themselves to the newly exalted medium of the public text. This is the generation that rang out Magritte's death knell to pictorialism and its illusionistic window onto reality, while seeing in Magritte's use of text an endorsement of the medium most conducive and convenient to the demands of contemporary living. Combining Magritte's precedence with Wittgenstein's instruction to see in the sentence a picture of the world, the conceptualist saw image making as redundant and unwieldy.

As a Postminimalist painter who came of age in the heyday of Conceptual Art, Schor's entire oeuvre shows itself to be confronting the impediments that negate painting. Like the Pictures Generation (Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, Sarah Charlesworth, Richard Prince, Sherrie Levine, et. al.), artists who revitalized pictures by making ironic and reflexive images rife with signage referring back to the process of picture making, the Postminimalist painters sought to revitalize painting by tautologically referring back to its material and thematic processes. But they faced a steeper challenge than the Pictures artists, who preferred photography, video and film as their media, in that painters had to contend with a choice of medium that the Minimalists had in the 1960s redefined at its essence to truly be sculpture, and that the Conceptualists deemed entirely obsolete for being inferior to the idea of the real world it sought to depict. Although painters have continued to defy these claims, no painter came close to formulating a counter-argument that laid the complaints of the Minimalists and Conceptualists to rest permanently. All of which seems to compel Schor to now pick up the challenge posed by Magritte and Wittgenstein, or really the artists and critics who persist in holding up Magritte and Wittgenstein (and others, such as Duchamp) as their filters for conferring canonic art.

The re-legitimization and recovery of painting from this reductionist and falsely essentialist turn is perhaps too much to expect from any one artist. But Schor is one painter who appears determined to keep trying. In this regard, Schor gives us indication that she may have stumbled on the pathway to countering those scolds who hold up Magritte and Wittgenstein as their bane to painting. And she may have found that path in the book that both informs the series Voice and Speech, and with which she portrays her avatar reading throughout the series. It has been a good long time since I've seen a recent work of art act out a tautological exercise about its own creation, in this case the reading and realization of a book that informs its own painted representation. That book is The Practice of Everyday Life, by the mid-century French Jesuit theorist Michel de Certeau.

I should point out, before commenting on Certeau, that for the majority of artists, as well as for the theoretical art cognoscenti, it matters little what theory of language and cognition Schor invokes with her painted contemplations on the nature of "voice" and "speech." What counts for them is how language and cognition theory can revitalize the esteem associated with the making of painted pictures. That's not to say that there is anything wrong with the delight Schor takes in the choices she makes in painting her "paradigm" of the good life of the scholar-critic-artist devoted to work, leisure, learning, and thought. But such delights may end up proving secondary if Schor has in fact stumbled on the pathway to the revitalization of painting through Certeau's theory of "voice" and "speech."

It is, however a laborious, contorted, and at times a fugitive path--perhaps too laborious, contorted, and fugitive for an artworld that likes its movements elegant and iconic. And some of these theories have circulated in postmodern discourse for decades, though not ever in a chain of reasoning leading to the conclusion that Schor may have pointed us to.

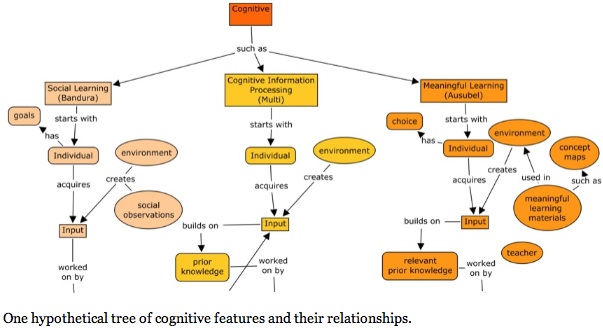

When Certeau alerts us in his book to the voice of our own experience that rises up and argues, negates, or concurs with, the authorial voice of theory, he is making reading and writing, in essence the text, his medium to be broken down and analyzed. Schor, on the other hand, is making the painted construction of imagery her medium, but she seeks to redefine its pictorial properties as a text. As a result, we find Schor attempting to bridge the chasm carved out by divergent modern media and the languages they have fostered with a painting that appropriates the structural representation of language originating with the voice and carried on with the collective compilation of voices in speech. The representation I mean is Schor's drawn word-windows replete with branching lines evocative of the "trees" used by researches and theorists to diagram the components and relations of syntactical, semantic, or cognitive processes undertaken in our habitual correspondences between the world and the self. But isolated words of the kind that Schor favors do not alone construct the kind of text to which Certeau, or any other language and cognitive theorist, refers. The "voice" to which Certeau refers is found in texts that establish a confident point of view--a voice that makes itself heard for being distinct and distinguished in the opinion it sends out. But there really are two, even more, voices sounding in a text--or really the reading of a text. There is the authorial voice of the writer, the voice of the reader, and the pluality of voices of anterior authors (authorities) that relentlessly haunt the writing and reading of texts. "Speech," meanwhile, is Certeau's reference to the colloquial language of the collective to which we belong and engage with daily, and which Certeau believes also precedes theory and texts, thereby threatening to drown out both the singular authorial voice of expertise and the voices of authority before it can establish itself within the inner ear of the reader.

Should we wish to be sticklers about Schor's transcription of voice and speech to painting, we might point out that Schor's shorthand approach loses sight of the very problematic features in the logical chain from writing to speech that can be shown to have evolved out of pictures--the very genesis which legitimizes Schor's project of picturing voice and speech as a logical return to writing's origins. The problematic we miss out on is found in the tracing of the authorial voice of the writer mingling with and overlain the voice of the reader. (Which is different from the painter's vision mingling with the viewer's sight of the painting, for being virtually the same as it was in the millennia in which painting was invented.) It's the competition and the compound effect of the authorial voice with the readerly voice to which Roland Barthes responds when he finds that the author's voice becomes so conflated with the voice of the reader that reading and writing become indistinguishable. Barthes realized that the reader writes as s/he reads even as the writer reads as s/he writes about, or in response to, what s/he has previously read.

In Schor's intervention we get only glimmers of this magnificent interweaving of reader/writer history, even though it is this very history that we must trace to see how writing is greatly in debt to painting. What I mean is that history by which a single textual passage published in the present day is the end result of a chain of reading-writers and writing-readers, each informed by prior generations of writer-readers, and each going on to inform succeeding generations of reader-writers. It's a chain that, though untraceable due to the breaks in our archeological and archival knowledge, stretches over millennia. But though our knowledge is fractured, the chain of reading-writer to writing-reader remains unbroken regardless of how long it takes the deceased generations of writing to link with new living generation of readers. The text, like the picture, can sit dormant for centuries waiting to be rediscovered. But when it is rediscovered, it extends the unbroken chain of reading-writing in the making (even if links of the chain have been lost to our tracing). Most importantly for painting and painters, this chain of reading and writing extends back to the origins of the written script--origins to be found in the calligraph and the ideogram, and before them the glyph, and before that the pictograph, which in turn grew from the painted figure that emerged from the painted picture as a whole. It's a legacy of writing that extends back to the first humanly-signifying scrawl; a scrawl that is entirely meaningful and pictorial at the same time. The task now is to show that the text so enamored by the conceptualist is really no more than a relatively recent generation of painting. And in Schor's systematic paintings, she is doing just that.

Yet the question remains: Just what can a painting tell us about the voice and about speech? It's not the same thing as stating--as have myriad painters since Magritte--that painting is a language or system of signage all its own. And it has been a rare artist who equated visual art's signage to be the equivalent of the voice or of speech, especially as the last century of artistic production was dominated by theoretical schools of structural and cultural linguistics, semantics, semiology, semiotics, and philosophers of language who agreed on very little except that there are great and slippery voids between the phenomena of language, speech, and the voice.

Schor appears to be bridging at least some of those voids by injecting into her painted fields diagrammatic windows occupied by word stubs, nouns that are sensory-evocative ("noise," "silence") or subject-evocative ("the self," "the world") and indicating with lines that they are connected to branches pointing to nowhere in particular except to some allusion of the world outside the frame. The message conveyed is that these word stubs refer to variables in the world that are humanly contextualized and supported by a larger system and process. Schor is, of course, coyly mimicking the semantic, syntactic, and cognitive trees we find populating theoretical books that mesh correspondences from among the various sciences. But it's not just Schor's coyness that is operative here. These relational trees with their alternating lines and words are often the last remnants of non-linguistic visual referencing found in theory, and as such are descendant from ancient pictographs that tell of their own world-to-mind relations, the kind we today call myth. More importantly, Schor's word stubs denote the linguistic relationships between the words that she disperses to sum up her paintings' function as a sign of the conceptual space extant between the "the self" and "the world." At the same time Schor enacts both a pictographic and linguistic division of the two central principles underpinning the entire history of philosophical debate.

Nearly everyone agrees that the "self" and the "world" are the two first principles of meaning, whether they underpin our cognitive processing of existence (ontology), knowledge (epistemology), experience (phenomenology), the mind (psychology), human relations (sociology) and so forth. It's a matter of which of the two--"the self" or "the world"--is claimed as prior. This is the source of the debate that commentators from classical times to the present have never been able to reconcile. But even this statement is fraught with controversy, as the very act of reviving the dialectic between "self" and "world" delivers a slap in the face to the poststructuralist, deconstructionist, and neopragmatist schools of theory, whose advocates declared such first principles (or grand narratives as some prefer calling them) to be false polarizations.

We would do well to be mindful that a theory which examines the correspondence between the self and the world doesn't necessarily polarize. If there is a great contribution made by post-structuralist cultural theory, it is to make clear that Difference is not polarity, nor does it by itself lead to polarization. And Schor seems to have stumbled on how the mis-identification of difference with polarity took hold of both the mind and of discourse. The very act of pictorially schematizing the world and the self visually as two different entities, say in a diagram of the self and the world, seems to suggest at the outset a signification of polarity by setting up dual poles. This assumption of polarity is no more than that--an assumption. In fact, what is established is a duality, the result of writing the two words out. But the mind unnecessarily "sees" them placed "opposite each other," suggesting two poles, and the overall tension of polarity. The division is a cognitive illusion, not a reality in the world. The self is part of the world, just as the world is a part of the self, though the diagram depicting the two would have us believing they are polar opposites. Just as Magritte's painting of a pipe is not a pipe, Schor's articulation of self and world does not manifest the self and the world. The signs, as words, are merely idioms that cannot be translated into one another's systems without a loss of content and context.

Idioms, both linguistic and visual, are in fact Schor's true subject. Idioms, we recall, are those familiar yet singular and independent features of an image or word that are not universally recognized and thereby fail to convey certifiable meanings of a sign of something we believe we know. In this regard, idioms are resistant to translation from one cognitive system to another. For that matter, the world that we perceive is filled with idioms, enigmas that have yet to be translated into human understanding, and may not lend themselves to such understanding. But idioms remain crucial in that they are the heuristic pointers to the limits of human sharing and experience, yet an experience that no less borders on a hypothetical world which the ancient Greeks, and later the philosopher Immanuel Kant, called the noumenal world--a world completely unknowable to humans.

Mira Schor shows us that painting, the ancestor to the text, still has the superior capacity to represent the idioms of the world that we receive through sight, yet which no photograph can record and that no sculpture can objectify. But just as Schor's painted neurological gestures (which we call painterly painting) share the same plane and surface with written words articulating relational status in the world, so do the two systems--painting and writing--evolve from the same neurological and cognitive branch of human response to the world. Somewhere along their branching evolutions, painting came to represent sight, while writing came to represent voice and speech. But the fact remains that writing, and through writing, voice and speech, by virtue of writing's descendance from painting, remains a kind of painting. This is the fact that outweigh's Magritte's differentiation of picture and text, while claiming Wittgenstein's language-as-picture hypothesis as reinforcing not Conceptual Art, but painting. It is by Schor's example that we can assert that painting remains the one medium best able to convey the idioms innate to the human nervous system--sight, voice, speech, and thought--and thereby the medium most capable of rendering their variant idiomatic significations in all their potential beauty and force.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.