Time. Space. Force. Matter. Structure. Motion. Nature. Anima. Humanity. Family. Birth. Self. Other. Love. Survival. Hatred. Competition. Death. Ressurection. Mysticism. God. Paradise Lost. Paradise Regained. Such is the short list of the literary, philosophical, and cosmological motifs at play in director Terrence Malick's newest film, Tree of Life, which this May was awarded the 64th Cannes Film Festival's Palme d'Or as best feature film of the year. Eminently lyrical and rapturous in the cinematic manifold that it kaleidoscopically brings into and out of focus onscreen with each turn of the Malick lens, Tree of Life is one of those singular cinematic milestones that makes its mark by being both breathtaking in its minimalist imagery and profound in its unspoken yet luminously metaphysical symbolism. (The real and hard lens turning, by the way, is the work of cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, whose work we know from such films as Children of Men; Y Tu Mamá También; and Like Water for Chocolate.)

Tree of Life takes shape as a modern yet primitive Bible story, a retelling of a secular, yet no less mystical, if cosmological Genesis set amid a Garden of Eden situated somewhere within a southern U.S. suburb during sometime between the mid 1950 to mid 1960s. In this modest yet spacious and tree-lined middle class neighborhood we find an archetypal rivalry between a father (Brad Pitt) and his three young sons playing out as it revolves around the affections of the young mother-wife (Jessica Chaistain). If there is more storyline, it's but secondary to the Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, and Oedipus, Laius, and Jocasta myths that Malick has conflated concisely and mercifully without their untidy cliches. But then, without warning or ample exposition, the setting flash forwards some thirty years to the life of the eldest son (Sean Penn), now a successful architect who works among an arsenal of glass skyscrapers and lives at arm's length with his beautiful but tentative wife in a house made of streamlined glass. Once established, the twin stories, though providing lean grist for the film's humanist center, never develops beyond the point of providing anecdotal evidence for the life of a boy whose rivalry with his brothers and father instills his adulthood with a morally agonizing guilt that is connected somehow with the death of his brother.

It's within Malick's refusal to flesh out and specify the Oedipal and sibling rivalries at work that the film's finest achievement is found, and that is its fresh yet familiar visual sketches of a cautionary tale about the Family of Man. Malick may sketch this branch of the Tree of Life in greater detail, yet he still chooses to visualize rather than narrate the human condition, and he does so in staccato rhythms reminiscent of silent film, with all its gaping holes and abrupt plot segues. These are techinical choices that signify much of the conflict stirring in the heart of humans is either largely unconsciously playing out or at best misunderstood. Whereas most modern narratives belabor the Freudian currents of human relationships while touting the screenwriter's godlike vision, it's Malick's counter instinct to allow the primordial impulses beneath modernity to remain undisturbed that strikes us as being the film's innovatively contemplative vein through what otherwise is an ancient, universal and religious miring of archetypes. And while the grandiose enactments of cosmology tempts today's cinephiles to proclaim Tree of Life to be on par with such past and internationally-lauded masterpieces as Andre Tarkovsky's Solaris and Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, one can also see in Malick's exposure of the naked unconscious governing the relations of the Family of Man ties to such films about family by Orson Welles as The Magnificent Ambersons and especially Citizen Kane.

Most importantly, to appreciate the manifold complexity of Malick's film, we need from the start to resign our cravings for conventionally resolved narratives and content ourselves instead with vacillating between the unresolved signage of familial rivalries and contemplations of a nature sublimely photographed and simulated. Ultimately, in its long and languorous 139 minutes, Malick's Tree of Life is in many senses a throwback to mid-20th-century vanguard cinema, and it's this nostalgia for modernist formalism with its great silent and still spaces that accounts largely for the film's appeal.

For this reason, seasoned filmgoers will likely be neither as astonished by its elliptical narrative structure and montage nor as stunned by the beauteous unfolding of sensory and conceptual permutations representing cosmological reality as they might have been three-to-four decades ago. Those viewers new to such aesthetic high mindedness, on the other hand, may require a cautionary word on how, at the outset of the film, our recognition of the distinction between what is "real" and what is "imaginary" is of little value here. Neither are the standards of cohesion and continuity that govern a good deal of art. Tree of Life could as well have been called Picture of Life in that it represents the meshes of the real (the shared) and the imaginary (the idiosyncratic) experience of life unexplained and unmediated by anything but consciousness at the same time that the features of that consciousness (impressions, expectations, facts) rarely fit together or follow one another logically.

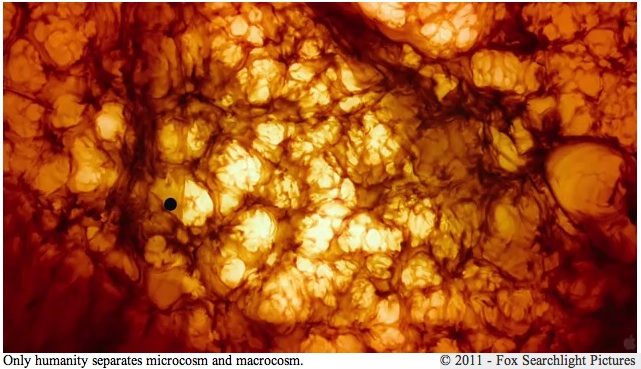

Remarkably, Malick doesn't depict anything in the film that is all that remarkable--except that we don't know how unremarkable it all is. This is especially true of the world's beauty, which as always in Malick's films is amply arrayed. Malick observes and simulates little that doesn't occur on a daily basis, yet his film allows us to see what we can't ordinarily see in the world because they concern things occurring on different levels of cognition--the microscopic, the macroscopic, the high frequency, the introspective--beyond our limitations, or because we don't take the time and trouble to see things in the ways in which the world's beauty can best be appreciated; or because we lack the sense of awe that predisposes us to seeing beauty at the outset.

But Malick's unconcern for reality and coherence is more artistically and emotionally profound for its fidelity to real human lives than the films made by the younger generation of post-surrealist directors like David Fincher, Darren Aronofsky, and Christopher Nolan, who also make consciousness and cognition the subject of their films. We should bless this younger generation for keeping the avant-garde from becoming totally irrelevant in our blockbuster age. Yet as ground breaking as such films as Memento, Inception, Fight Club, Requiem for a Dream, and The Black Swan prove to be, such films divorce the imagination from reality with a hallucinatory savagery. By contrast, Tree of Life, in its reverence for nature and its fidelity to human decency and simplicity, proves itself a film full of grace, a rare compendium of the searching mind and soul both displaying and inviting contemplation on the order of things in the manner of an earlier generation of directorial luminaries--Tarkovsky, Bresson, Resnais, Antonioni, Bergman, Kubrick, and occasionally even Godard most prominently among them.

In being the last representative of this old wave of formalists, Malick stands curiously in defiance to the newer generation of formalists who have rewritten the rules of surreality with hyper-structural narrative exercises that set action in the foreground while abandoning the space of contemplation altogether in exchange for the sensory overload of Computer Generated Imaging (CGI) and madly paced escapes to nowhere certain. Instead of the Whitmanesque immersion of self in nature so dear to Malick, we're presented with the dream within the dream within the dream engineered forcefully in Nolan's Inception; the induced hallucination or narcissistic obsession escalating rapidly into psychosis that Aronofsky feeds us in his Requiem for a Dream and The Black Swan, and which informs Fincher's Fight Club and the erasure and treacherous re-tracing of memory in Nolan's Memento.

By contrast, in its mimicry of life and nature, Tree of Life dissolves narrative--at least linguistic narrative--to its most visually fluid state, allowing iconography to flow into swirling eddies of pictorial flux, not merely convergences of information, but projections of life that despite their conceptual and simulated forms seem perfectly in keeping with our experience. Tree of Life is less a narration than it is a pictorial genesis, evolution, and lineage of timeless primordiality to the present-day personal. We witness a succession of conceptual streams of thought flow through one another on a variety of physical levels, see theoretical manifolds converging, all as if before the formation of language. It's Tree of Life's perpetual flux and tensions, even more than the relentless beauty of the montage and action, that keep Tree of Life vibrant and provocative. In fact the beauty of the film is too constant, to the point that its run-on picturesqueness at times becomes tedious, even exhausting.

Our threshold for beauty, like all other appetites, is limited and requires variation, so that when we are confronted with an overload of sensory gratification, we become inured to it. In this respect, Malick's 1998 masterpiece The Thin Red Line is a far more effective vehicle for highlighting beauty in that here Malick keeps beauty constrained, sparsely and momentary displayed when allowed to surface at all. In confining the beauties of The Thin Red Line behind a succession of war clouds that allow rapturous sunlight to break through only on occasion, and then only with the fleeting sight of it cascading across tropical grasses, then retreating again. It's through such momentary illuminations that beauty is brought to a premium, made stark, dramatically theatrical for its contrasts, while making itself felt as life-sustaining--like priceless air breathed in after near suffocation. But even air in too great a quantity makes us pass out. Which is why, to paraphrase a line from the rock song Lightning Crashes, Tree of Life's overindulgence in the high picturesque seemingly "puts the glory out to hide."

Because of the sensory overload of Tree of Life--which to a large extent is the product of a film vacillating between sensory and ethical macrocosm and microcosm--in the rare instances that the conventions of storytelling intervenes, we feel ourselves to be beached on high ground after a great flood subsides. How many viewers, I wonder, are struck with the realization that the macrocosm and the microcosm would be wholly undifferentiated were it without human consciousness at the center to define their difference. Then, too, the interludes of cosmological forces we witness on screen are really Malick's conflation of the imaginations of contemporary astrophysicists, genetic evolutionists, and religious clergy granted enormous leeway in their postulations of creation. Still, they are powerfully vivid simulations of the largely unseen and near-unimaginable forces standing in for the God intended to receive the personal prayers and pleas of billions of human souls. In effect, Malick lets us see why the existentialist god of Ingmar Bergman remained silent and impassive. Or so he leads us to believe. I should here point out that it is really a phenomenological view of life that Malick exposits--which is just another way of describing a deeply personal yet intensely penetrating life experienced in wholly sensory and personal terms.

Malick's most devoted admirers may see in the film the narrative seeds that make Tree of Life a kind of prequel to The Thin Red Line. But whereas The Thin Red Line is drawn tightly around the theme of the noble male as he greets the loss of his innocence by joining the homosociality of the U.S. Armed Forces and combatting the pathology that has ensued in the intrusion of humanity onto nature, Tree of Life by contrast traces the familial conditions that form the conflict unleashed on nature and the world in the development of boys to men. In other words, the fighting that inflicts agony onscreen in The Thin Red Line as a necessary response to brute force is charted in Tree of Life as the outcome of the simple Oedipal rivalries between fathers and sons for the love of wives and mothers and the Cain and Abel syndrome dividing brothers in the competition for the affection of fathers.

Relatedly, some of the best scenes in Tree of Life are of the brothers roaming with a small gang of neighborhood boys looking for trouble. Malick excels at capturing the relentless movements of the boys in short, successive, near-spastic camera motion and editing that combined mimics the unease of young bodies propelled by the onrush of fresh testosterone and made to seem animal like with the boys' heads turning every which way in displays of collectively-reinforced attention deficit. These are body movements we've seen before in Malick films, though intensified by the malaise of grown men in conflict: with the soldiers of The Thin Red Line storming a village on Guadalcanal Island suspected of hiding Japanese infantry, and in The New World when the Jamestown colonists and the Powhatan tribe are launched into their fiercest battle.

Tree of Life could as easily have been made as a montage or cross section of the vast array of humanity striving, succeeding, failing and railing against all odds, or in occasional accord with the way of things. But while an impersonal and universal vision defines the lyrical visions of such avant-garde film patriarchs as Stan Brackhage, Michael Snow and Hollis Frampton, or even Stanley Kubrick's famous speed-of-light finale for 2001: A Space Odyssey, Malick, like Ingmar Bergman, is drawn to the specific case story that the universe, or God, spits out on the human scale familiar to us. But whereas Malick's earlier films have always relied on sparsely parceled dialogue among characters to propel their stories forward, Tree of Life almost dispenses with dialogue altogether. The effect is disorienting--until we realize that Malick intends us to think less about both stories and our individual lives and more about what we share with the Family of Man--which means what is largely beyond our control yet shapes who we are.

This seems to be the reason why we hardly know the names of the characters until reaching the film's ending credits. Everyone is simply "father," "mother," "brother," "wife"--the human relations that are as interchangeable with identity as are symbols or numbers. The same goes for the glimpses we're provided at time's passage. We only realize the story has elipsed some thirty years upon seeing the sudden appearance of the adult oldest son (Sean Penn) in place of his child self (Hunter McCracken), or by the 21st century skyscrapers, shot from unusually low camera angles, now commanding attention in place of the 1950s suburban houses shot in conventional, comforting perspective to signify homes we either knew or wished we knew. And while we can see that only two brothers remain where we remember there had been three, we must strain to hear the cell phone utterances (we can hardly call them conversations) that re-establish the relationships of the children, or to learn the fate of the missing brother. It is only in the final scene enacting a rapturous end-of-the-world convergence and reuniting of souls on a metaphorical beach that we have our suspicions confirmed about Malick's mystical vision of the reunification of family that is to be our redemption.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.