Many of the cibachrome collages and all the black-and-white photo enlargements discussed here are included in Doubleworld, The New Museum's exhibition survey and catalogue of Sarah Charlesworth's art on view from June 24 through September 20, 2015.

New York has long been overdo for a Sarah Charlesworth retrospective. Throughout the summer of 2015, the New Museum filled the void with Doubleword, a partial-survey of Charlesworth's work curated by Massimiliano Gioni and Margot Norton, that steered close, if perhaps too conservatively, to the theoretical predilections of an artist who contributed among the most critically substantive and culturally capacious work of the so-called Pictures Artists emerging in the late 1970s and early 1980s, though such a survey should have occasioned New York before the artist succumbed to a cerebral hemorrhage in 2013. If the show lacked anything, it was the contextual referents that might have been afforded by a larger institution possessing a diversely capacious collection with which to surround, vitalize and debate Charleworth's expansive sweep of pictorial and ideological systems found throughout global cultures, while yielding a richer and more summary experience of the structural underpinnings joining together all the cross-cultural relationships among art and artifacts populating Charlesworth's art.

Imagine if Charlesworth's work were exhibited more capaciously at the Metropiltan Museum in New York, where her feminist, poststructuralist and anthropological deconstructions of world cultural iconography could be immersed within, greeted by and made to rival the art made within that society, whether it be a tribe, nation or civilization. The delight of seeing and feeling her expanse of heterogeneously-deconstructive appropriations absorbed by or rebounding off an array of indigenous arts and artifacts in the Met's galleries could feasibly make us see both Charlesworth's work and the iconography of the culture and period being appropriated responding one to the other in an intriguing morphogenetic interchange that alters our view of both the original art and the appropriated representation. Feasibly, entering a Charlesworth retrospective immediately upon having just left, say, the Met's Renaissance galleries or before entering the Asian or Oceanic Art wings, could effect in the mind of the viewer a cultural layering in he viewer's mind that spurs an ecstatic epiphany or provokes a critical confrontation, depending on whichever one's background and ideological leanings are prepared for. Would we, as a result of encountering Charlesworth's pictorial fields saturated with images of object-metaphors, carry with us a readiness to look for the metaphor and analogy at work in the art displayed in the museum's other exhibitions and collections? Might we find the original period painting or mask to be in agreement with Charlesworth's extraction and isolation of similarly-produced images? Could the appropriated images augment or deflate the iconic power of similarly, indigenously-charged cultural objects? Or might the comparisons make us more critical of Charlesworth's appropriation of the signage of art and imagery, especially when the comparisons are of objects and images made outside Modernism and the West?

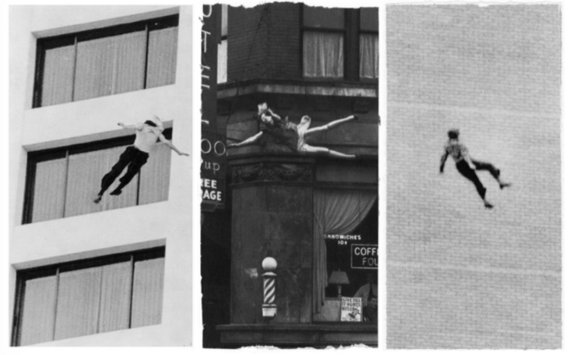

Until a more summary exhibition and context ifor Charlesworth's work materializes, the New Museum's judicious if austere exhibition fills the void with ample representation of Charlesworths visual, analogical and political concerns. It also supplies viewers with the first complete New York compilation of the 1980 series, Stills, the fourteen large-scale works Charlesworth rephotographed from press images depicting people falling or jumping off of buildings, and that were loaned by The Art Institute of Chicago. And as the curators remark, with 9/11 still in vivid memory, we look at the bodies caught in mid air and personally recontextualize the work with a recollective irony that Charlesworth couldn't have personally foreseen, yet which, in the manner of all great art, unconsciously anticipates.

Doubleworld at the New Museum in New York City, 2015. Collection of The Art Institute of Chicago.

Charlesworth never assembled a body of work more existentially confrontational to our imaginative reaching for an exalting human continuity commonly called 'spiritual' than this body of images depicting the forces of physics and nature at work in a person's violent demise. But Charlesworth's serial replication also defies our expectation of such imagery to cheapen the tragedy portrayed by instead magnifying the personal tragedy of each jumper for the viewer. Charlesworth in fact has produced a typology of tragedy and death that can be quantified, however terrifyingly, as both repeatable at will by others and enacted often enough to be numerously photographed at random. Yet, because Charlesworth's prints are second-generation to journalistic sources, like the Death and Disasters silkscreen prints by Andy Warhol to which Charlesworth's Stills are indebted, her versions of jumpers and fallers represent rather than enact the journalistic function of recording an event. With regard to that journalism, Charlesworth has mindfully selected photos of tragedy that free the person behind the camera from Susan Sontag's indictment of the photojournalist for making a choice of photographing victims or rescuing them. As the falling victims are beyond saving, the choice to photograph is the only moral dignity left the photographer witness. In re-presenting the dignity of fourteen photographers, Charlesworth has countered whatever moral disparagement accompanies their pictures of suicides with the moral rectitude of the photographers.

and installed in the exhibition, Doubleworld, at the New Museum in New York City, 2015. Collection of The Art Institute of Chicago.

.

Charlesworth's typology of imagery here also heightens the serial effect of contrasting the despairing solitude of the suicide with the unforeseen companionship of a group of similarly desparing jumpers in spirit. Yet Charlesworth differs from Warhol in that Warhol appropriated images of accidental and unforeseen tragedies with no death motive to rationalize, whereas in Charlesworth's Stills, the group display solidifies a sociological and statistical profile of distress that is a counterweight to whatever subjective emotional or spiritual strength the individual suicide lacked in life yet found in a death chosen to face Camus' "only one really serious philosophical problem" -- the choice that likely counts as each depicted jumper's greatest courage in life. The jumpers of the World Trade Center terrorism taught us about that final courage, though of course they are not suicides (as some of the jumpers in Stills are not). In fact, Charlesworth has done no more than made them a group slely on the typological basis of the act of jumping to their deaths, and in doing so, besides calling on an empirical method of categorization,Charlesworth as well has made a spiritual gesture in their assemblage, as spirituality is nothing if not aimed to effect communion with some collective representative of a larger purpose than any that an individual alone can effect. The 9/11 jumpers taught us their numbers reinforced their choice for the more courageous action left them over the end that rendered them as abject victims. Then too, the greatest union of humankind is found in death, even if death be the end of the spirit that is consciousness. By collecting their images from the archives of photojournalistm, Charlesworth has visually extrapolated each lone jumper into a communion with all other jumpers, and thereby assigns them as a group both to a sociological and a spiritual context, if it only be but in the minds of viewers.

Perhaps the largest significance of seeing a series of frozen-but-plummeting subjects is what they imply about ourselves as a culture riveted to such seemingly-gratuitous displays of tragedy. I don't mean that we are reduced to sensation-starved gawkers. In fact it is the opposite that occurs in that our compulsion for such imagery renders us as a collective in profound empathy with the dying figures through the recognition of our communion with them as witnesses to the final and lasting remnant of their deaths. Our justification for being drawn to the tragic image is also justified by seeing in each jumper's demise a reminder of our own unconscious approach to death and its displacement of consciousness of the self with the presumed non-consciousness of the world. In this respect even the atheist who sees death as final participates in (and here the reader may make a choice between) the spirituality/ phenomenology of ones own personal consciousness, and in the case of encountering Charleswprth's Stills, a consciousness of the approach to one's own death. (Both spirituality and phenomenology are defined by consciousness and choice.) All this comes pouring out of the serial depiction of death that makes obvious -- through the repetition of a single type of death arrived at by choice -- that spirituality/phenomenology as consciousness is actively at play each time that a consciousness chooses to continue or end itself.

If phenomenology was the 20th-century atheist's choice of system to describe the subjective experiences that were more commonly called spiritual, Charlesworth was one among postmodern intellectuals who in recent decades could entertain atheistic tendencies without shunning the terminology of the spiritual even if she deconstructed the myths of traditionally inherited spiritual systems. The ubiquitous 1980s team of curators, Collins and Mollazo, summed up this greater collective conflation of the phenomenological consciousness with the spiritual consciousness at work in Charlesworth's art when they included her, along with several artists with similar pictorial and experiential concerns, in their 1986 exhibition, Spiritual America -- a title that was only in part ironic for implying that the movement away from conventional spirituality by the 1980s generation was no more nor less than a movement that sought to renew faith in our own relationship to the world by being brutally frank about the fallacy of any spirituality prescribed by a hierarchy, text or miraculous narrative rather than that derived from a life in concert directly with the animating force of nature.

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, CA, Cleveland Museum of Art, OH, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

Charlesworth discussed with me in conversations preparing for her inclusion in exhibitions and articles I arranged in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and again for her inclusion in the 2012 Huffington Post Series, XX Chromosocial: Women Artists Cross the Homosocial Divide. In each of our conversations, she talked at length about her efforts to heighten the signage of art that could only truly be deemed 'spiritual' -- a term she used only when it was clear what she intendef by it -- when one's individual and subjective relationship to nature is coupled with a criticality of the cultural systems, including institutionalized spiritual systems, that we inherit yet shut down personal channels of inquiry, growth and empowerment. We can see from Charlesworth's art that she considered the likelihood that spirituality can be reconciled with both atheism and denial of an afterlife. But then from the standpoint of the photographic arts, the spiritual does not reside in an imagination of the afterlife, as it might in a more phenomenologically-fanciful artistic process such as painting, music, or literature. If there is a spirituality to be represented by the photograph it can only be the spirituality derived from an empirical and objective evidence of life. But though photography provides an index to the actions and occurrences that compose a living spirit, it cannot document the suicide's and the fire victim's conscious will to desist. The will to desist is recognizable only through a logical inference, yet it is a logical inference regarding a spiritual choice, just as we know by logical inference what it means to be human and therefore what it means to will that a human consciousness ceases to be humanly and materially bounded by choice despite that that knowledge is forever denied the lens of the photographer.

As to the materialist and positivist bias that would impose an unmerited closure on the subject of spirituality, we may point out that just as Charlesworth's deconstruction of the metaphors and metonyms of sexuality and gender require her to immerse herself in the field of the dominant ideology of the male authorities legislating past and contemporary sexual attitudes, myths and conditions, the same immersion into that field is by necessity required for her to deconstruct the dominant and authorial metaphors and metonyms regarding spirituality. And though Charlesworth can be seen as ambivalent on the subject of spirituality, that ambivalence itself becomes for her a purposeful ambiguity, a kind of spirituality by default in her activist choice to negate authoritarian constraints.

In a sense, Charlesworth's art was a 'Personal Religion' in which she had considerable Faith in Doubt, and where the Spirit resides in The Sign. That may strike some to be a non sequitur or self-negation, but it is the reconciliation of an age in which 'Truth' has in many enclaves become at best a relativity and at worst entirely suspect for the closure of thought it invariably imposes. And for an artist such as Charlesworth, 'Personal Religion' and 'Faith in Doubt' were tangible indexes to an undercurrent zeitgeist ascending to the surface of mainstream discourse, which for her was Structuralism and Post-Structuralism. While Charlesworth never uttered the word 'religion' in my presence, and she only reticently let the word 'spiritual' slip from her lips, her reticence is what conferred those moments that she did sound the word with a measured immaterial power that reinforced her logic. Similarly, the restraint with which she decomposed the compositions of art history and images taken from journalism and advertising allowed the traditional and institutional 'spiritual' components to empty out, erase and then refill, recompose and recharge the obvious and cliched pictures enough to make us stop and allow them to gratify our attention despite that we recognize them to be second-, even third-hand references.

Although Charlesworth gave me indication in our discussions that she was open to the idea of spirituality in the larger sense of it being integral with Nature, it was Betsy Sussler, editor of BOMB, was conscientious about posterity in 1988 when she recorded Charlesworth's acknowledgment of her own contradictory stance. When Sussler cites the ancient source of power informing Charlesworth's imagery, and which is in fact an authorial/authorizing identification of her position in the world, Charlesworth counters: "What I'm saying is frequently these loaded images or objects are used by me without my attaching a particular significance to them. In other words, what I'm doing is letting whatever power, whatever affect they have, work on its own."

Yet within minutes Charlesworth seemingly contradicts herself, though really she is expressing the ambivalence and attraction to ambiguity that fills the space of an ideological deferral, an ambiguity that is especially attractive when concerning established spiritual systems that are a product of conditioning within a secular and democratic society marked by the mediation of ideological and cultural difference amid an imperative individualism. Sussler has implied that Charlesworth wouldn't feel such ambivalence were she to connect to the account of a feminism that had been historically empowering to ancient women ministering, say, an oracular and healing mysticism that though absent in the present has a parallel feminism being expanded by women's roles in the development of science. But Charlesworth's retort to Sussler is also an open acknowledgement of the structuralist tradition that puts such a diachronic paradigm as history well beneath the synchronic system to which Charlesworth subscribes to in her schematic depiction of an art informed by a theory of the sign systems at work in a given culture. That Charlesworth began her career as a Structuralist who values systems at work in the present over accounts for a spiritually empowering feminism or matriarchy in the remote past indicates why she is self-consciously hesitant to cite her subjectivity as a mode of spirituality at work in her methodology despite that her methodology is an open interpretive process.

"I use images drawn from the culture because I'm interested in each piece being an interface between my personal subjectivity and a given world. A kind of langue and parole situation where I am speaking of the world through things of the world but via my own particular arrangement, construction of the world ... I'm confronting a given world and trying to discover its architecture, its formal and political nature. Whereas in more recent work, I'm constructing a consciousness within the world. In a piece like the Self-Portrait, I'm literally projecting a visual image or psychic image of myself into the world. ... I see myself as casting my world back into the given world. It's like a reformulation of language, a recreation of a new metaphor."

Yet the BOMB interview goes on to clarify not only Charlesworth's acknowledgment of her ambivalence toward spiritual systems and their signage, but also her admission of having an attraction to the power such potentially mystifying signage wields. Even the materialist and positivist must admit that what many regard to be spiritual about images and ideas is the power that they appear to wield both in the mind and in the world. In such a case the argument over whether or not we call power 'spiritual' may be more than semantic as we recognize that the idea of spirt and spirituality holds considerable sway over people's actions. Such sway requires recognition beyond the field of sociology so that those people's valuation of the spiritual is substantiated in their description of a deeply felt power within them despite it not being material or verifiable.

It becomes clear in the context of there being "an interface between my personal subjectivity and a given world" and in her project of "constructing a consciousness within the world" that Charlesworth didn't see an incongruence between the material and the spiritual constructions of the world. If they are different yet continuous it is because one is subjective to the individual and the other is objectively shared by the collective. In this Charlesworth perceived the world in a way akin to a physicist who differentiates between matter and energy while understanding that one can be converted into the other because a continuity exists between them despite their different properties and functions. Life and death is one such conversion. Thought and action another. If spirit and material are different yet continually contrasted then they are likely continuous. The difference yet continuity of spirit and material in this way are akin to the difference yet continuity between languages or signs and the things in the world they refer to. Charlesworth enacts such a continuity of opposites in her art of signs and metaphors, but in doing so she is summing up the equation of all artists who craft an art of representation, for that matter all visual sign systems from mathematics to advertising, and all languages, visual and aural. It may seem too simplistic to be possible but the difference and similarity between spirit/mind/sign and material/object/signified are equal if not the same. And we see this play out in Charlesworth's work.

In this sense, all of Charlesworth's work is in some function a commentary on the spirituality that is empirically derived from a culture that is in alignment with nature. Yet Charlesworth implies in her conversations and art that she believed all culture must be revised to be made personal to each generation--a phrasing that I cannot but be reminded of Sontag's aphorism at the opening of "The Aesthetics of Silence", that "Every era has to reinvent the project of "spirituality" for itself. (Spirituality = plans, terminologies, ideas of deportment aimed at the resolution of painful structural contradictions inherent in the human situation, at the completion of human consciousness, at transcendence.)"

It is this necessary personalization of the resolution of structural conditions that impelled Charlesworth to chose not photography of the world as it appears to us as her medium and image resource, but rather the rephotographing and the redefining of prior and recognizable iconographies that became her springboard for an art about the inner, natural and structural workings of civilization knowable through the signage of its culture. In this narrowing of the field of her inquiry, Charlesworth implies that visual history and visual literacy is more self-reflexive and thereby more reliable as an index to human proclivities sexually and spiritually empowering than is writing.

Visual history, in Charlesworth's work, is to be the premiere source of education and enculturation. In this she inherits Jacques Derrida's deconstruction of the historically perpetuated 'logocentrism' of the text -- the innate belief that words convey the well-sounded truths. For unlike artists, writers often mistake their words to be recordings of some larger and distant historical past or truth rather than the marking or recording of thought-in-the-present that it is. By contrast, visual artists don't by and large presume to represent history because artists generally acknowledge their art to be records of no more than the subjective and phenomenological moment at hand. This is why Charlesworth devotes all her visual resources to locating and rephotographing prior images. For in recalling and appropriating prior images, Charlesworth acknowledges that the artists of bygone eras ironically made more reliable records of each's own present -- our history -- than the texts which presume to record histories not their own.

In the same way, Charlesworth taps into the spirituality of the image makers, often of image makers responsible for disseminating the iconography of spiritual systems that today dominate the cultures to which they are indigenous or adopted. Although spirituality and faith were not defining principles or ends to be attained in Charlesworth's visual and critical efforts, spirituality and faith-based systems count among the premiere metaphysical systems whose signage Charlesworth sought to deconstruct -- 'deconstruction' being the zeitgeist term we shared throughout the 1980s and 1990s, thanks to Derrida and his numerous advocates. Yet deconstruction remains vital for offering a shared predilection among the more relativistic artists and critics of a Liberal and Left ideological character, especially those concerned with ensuring that our inquiries into the bases of cultural activism and art are marked by the reflexive acknowledgment that whatever system of analysis is being edified in the process of deconstruction, we understand that edification will as well be deconstructed by some present or future antagonist, if not first by ourselves.

Here the authors of any system (as authorities of systems by virtue of their authoring) are reminded of their demise and replacement, something that numerous historical spiritualities failed to acknowledged. For all attempts to climb outside and understand the larger society, culture and language that we inhabit are but vain attempts to define a composition of humankind so much larger than we can contain, control and define. This is the fallacy of composition through which the composition of all that is human and natural is magnified to a scale that composes, controls and defines us, and therefore is a thing we can only approximate in part and by inference, and never in totality as some in science and religion futilely try, yet only fail to do. In the absence of absolute truth, the resultant crisis of faith in the modern world requires that the enlightened spiritualist accept that the only irrefutable thing about the spirit is that it is unverifiable. Therefore spiritual propositions can only be irrefutable in the admission that they are unverifiable.

As this realization coursed through rational society in modern cosmopolitan centers, and certainly by the late 1970s, when Charlesworth began her deconstructions, secular society had successfully implemented the interaction of diverse peoples regardless of their conflicting faiths, however temporarily joined together for public and pragmatic exchanges of skills, material and information.

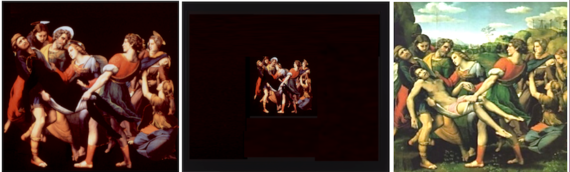

Interestingly, the work missing from the New Museum show--and that which may be most provocative -- is that in which Charlesworth most explicitly reflects on the modern crisis facing faith based-systems. With Judaism, Islam, Buddhism and all other faiths being in minority status in the West, Christianity is naturally the domineering institution blocking liberal freedoms. Christianity thus by its own imperial tendencies invited deconstruction in Europe and America, and Charlesworth saw to it that her own deconstructions were wielded in one bold visual stroke -- a kind of blackening of the temple lights or eclipse of a heavenly body -- as a refutation of the authoritarianism of Christianity still extant. In this regard two works from Charlesworth's Renaissance Paintings series stand out for counting among Charleworth's most intent and potent deconstructions of the signage of the authoritarian religious ideology that historically dictated the valuation, codification, perpetuation and legislation of social relations at all levels of society.

Both works are comprised of a blackening or erasure of the central iconic figures of Christianity -- Christ and his mother Mary -- both literally cut out and voided in a symbolic deconstruction of all inherited and institutionalized faith. While the defensive Christian might take offense, an understanding of Charlesworth's aim in detaching both images from their customary social contexts enables the more open observer to understand that the intent is not to defame or outrage but to invite analysis of the power both personages-as-signs wield in the centralizing and defining locus of power for the faithful. Yet it has been a signage historically attached to, if not responsible for, imperial and hierarchical persecution and repression through its enforced ideological valuation, codification, and cultural perpetuation of Christian patriarchal moral and sexual imperatives. In the less emotionally-charged and rational context of the mythologist or the contemporary secular cognoscenti, Charlesworth clarifies the underlining function of the inherited signage of the 'resurrected' Christ and the 'virgin' Mother as object-metaphors and metonymies in the codification of ideological, sexual and political systems that inspired entire cosmologies, histories, legislations and governments.

Of course Charlesworth was never interested in censoring a faith for the faithful. But she was interested in removing the Christian ideology from the legislation of the language and the law of the democratic society she inhabited --again, turning off the temple lights within the secular space and discourse. Here is where Herbert Marcuse's impact on Charlesworth is most evident. In response to Freud's 1908 Theory of Sublimation, by which he sought to explain the psychological mechanism of transforming pleasurable-yet-socially-unacceptable impulses, obsessions and ideals into socially acceptable actions and behaviors, Marcuse countered Freud in naming Repressive Desublimation as the modern Capitalist social mechanism elaborated to counter religion's socialized Sublimation. Desublimation, according to Marcuse, is the means by which Capitalism facilitates the maximum capitalization (profits). Desublimation does this by valorizing the Pleasure Principle that sublimation counters, and thereby slackens the culture of morality or ethics through its arts and entertainments. If this historical realignment of psycho-sexual principles is important to an understanding of Charlesworth's work, it is because she knowingly slipped between these rival moral/pleasurable processes to depict them at work even as they were deconstructed by their own constructions--the signage of sublimation and desublimation at work in the valuation, codification, perpetuation and legislation of social relations at all levels of society.

For Charlesworth the next step is to effect a sublimation of the power which spirit/mind/sign harness in the material/object/signified to counter the repressive desublimation of modern civilization. And the domain she saw most requiring a renewed sublimation was politics, particularly sex and gender politics. It is in the context of gender politics that we see her work out new configurations of power relations among the signs and metaphors of sexuality and gender in such series as Academy of Secrets, Objects of Desire and Renaissance Painting. In these three series, Charlesworth demonstrates that the world's living languages are so thoroughly stratified with fossils of male dominance that even as patriarchies erode, textual, oral, and visual systems are generations away from being purged of mythic and metaphorical gender. It is this kind of essentialism at large in civilization that made Charlesworth revalue doubt and ambivalence as a source for an anti-essentialist culture in alignment with nature--the very definition of spirituality for the naturalist--to the extent that she accepted the subtle knowledge that nature imbues as a potent anti-essentialist antidote to the ancient notion of spirituality as an essence of human creation conferred by the divine.

In Academy of Secrets, which the New Museum show largely neglected, Charlesworth ferreted out the metaphors and metonyms deposited in language by past and present civilizations. We know well today that the history of relations between humans and objects was for millennia dominated by the male sexual imagination, one which predicated the world through language--literal and visual--projecting mythic gender onto inanimate objects and the metaphors and metonyms they inspired. men assumed hegemony over the naming of things and, thereby, of the engendering of metaphor. But as late as the 1980s, when Charlesworth was making Academy of Secrets, even intellectual and left-liberal social enclaves had still not assimilated the feminist revaluation and activism against patriarchal language.

In Temple of My Father, Charlesworth elucidated the signage that was consequential of this hegemony, as the structure of language and myth revealed the array of male-dominated conscious and unconscious male differentiation and integration of values that came to bear on all political, legal, religious, economic, and domestic codes. The patriarchal biases continue to infiltrate every level of human operation through language with some languages, such as the romance languages of Europe, assign nouns and their modifying adjective with gender. The world's living languages are so thoroughly stratified with fossils of male dominance that even as patriarchies erode, textual, oral, and visual systems are generations away from being purged of mythic gender.

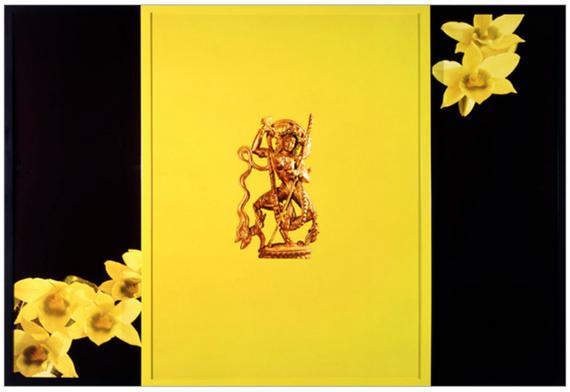

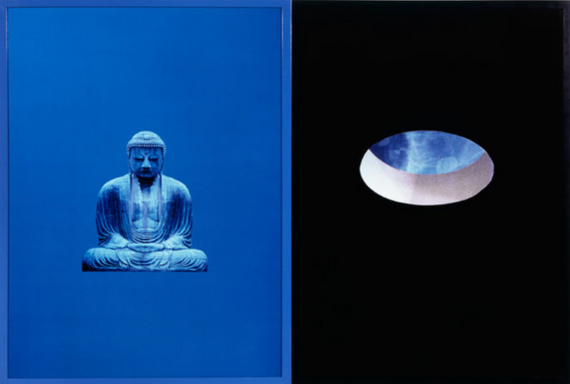

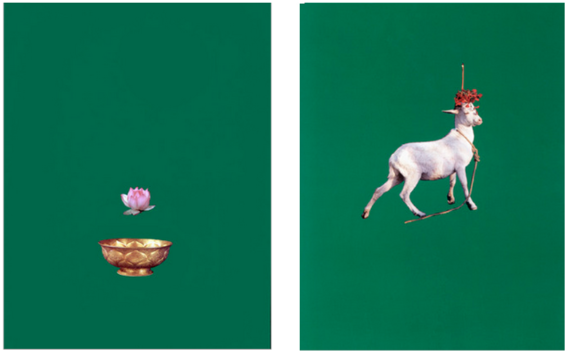

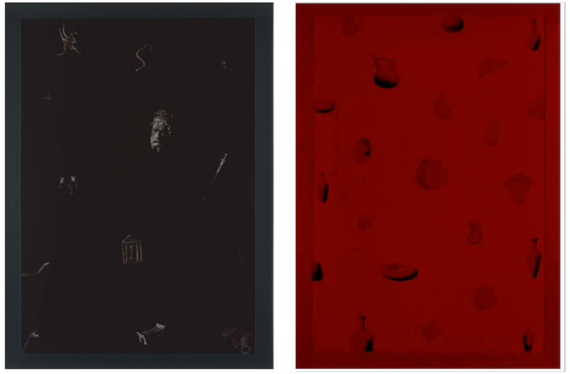

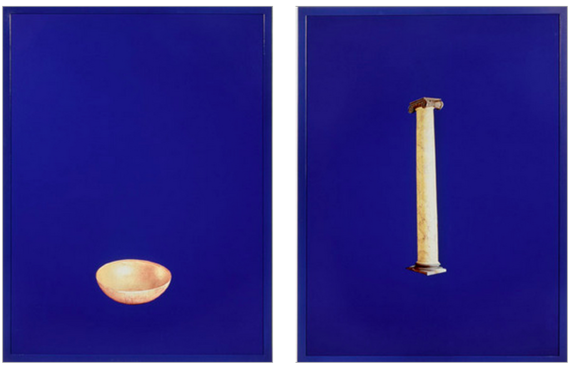

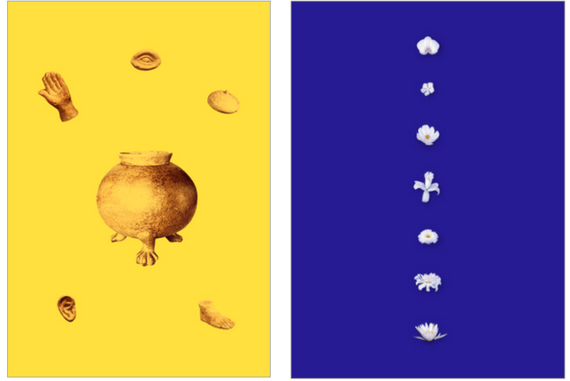

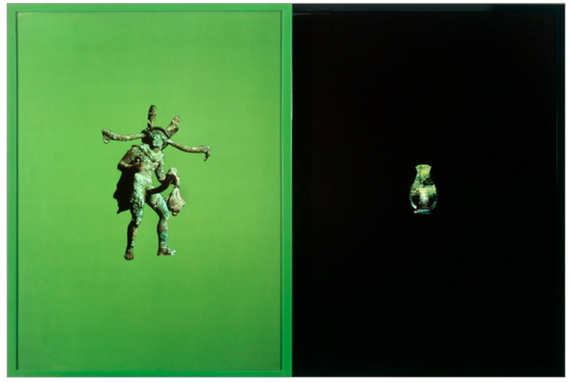

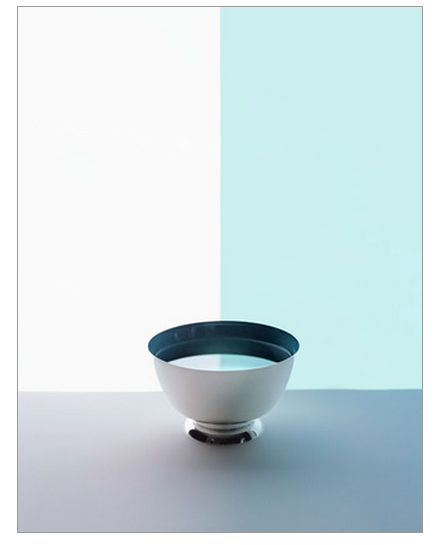

Charlesworth here refigured a series of protean and amorphous signs -- what she enjoyed calling "mental bodies" -- from textual, oral, and visual languages composing the oceanic medium of the unconscious. Once fashioned, Charlesworth then saturated these mental bodies in what we then delighted in calling multicultural, feminist, and anti-imperialist plenums. But before she could cast herself effectively in language, Charlesworth had to first "disembody" the languages she inherited and filter out all atrophied and despotic speech elements inhibiting personal growth. Only then could she edify a new model of the unconscious -- one freed from its former paternal circumscriptions. Charlesworth begins this process by first extracting and isolating the object-metaphors from the world's ideologies, myths, cosmologies, history, and arts. Once done, she suspends the object-metaphors in evocative, monochromatic fields which substitute for historic and personal contexts. The color fields and their frames -- which have been matched precisely in color by master framer Yasuo Minagawa -- together effect an objectness that distinguishes Charlesworth's work from conventional photography while suggesting that the cultural ownership of their symbolisms and significations is a kind of hermeneutical framing and readings of objects as metaphors having culturally-assigned emotional values (the blue of tranquility, white of purity, black of domination, magenta of sensuality, yellow of celebration), at the same time that their groupings suggest common metaphoric significations (gender, status, morality, spirituality, power). As an analogy of cultural analysis the works suggest that once the cultural deconstruction makes cogent the relative political values (patriarchal, ethnocentric, religiocentric, etc.), the deconstruction begins automatically, even if latently, in the mind of the viewer.

A feminist theorist such as Alice Jardine might maintain such a process to be within the activism of what she and other 20th-century feminists called 'gynesis', the process by which the `feminine' signifies, not woman herself, but those `spaces' which can be said to conceptualize the master narrative's own `non-knowledge', that area over which the narrative has lost control. This is the unknown, the terrifying, the monstrous -- everything which is not held in place by concepts such as 'Man', 'Truth', 'Meaning'. But even before Judith Butler presented her formidable anti-essentialist critique of feminism in the early 1990s, Charlesworth sought to dismantle all stereotypical gender, political, and ethnic myths that assigned culturally sanctioned "masculinity" to one general set of metaphors and those assigning "femininity" to another. Thus, instead of interpreting Temple of My Father as designating "masculine" metaphors in general, Charlesworth acknowledges how each object-metaphor can be deciphered according to an individual's personal code for masculinity, particularly as that code reflects one's inheritance from the father. Although Temple of My Father does indeed yield a classical reading of patriarchal metaphors, their identification and suspension are only the first steps in exorcising patriarchal influence and the onerous myths it spawns.

Of course Charlesworth doesn't leave the "phallic" temple uncontested; it is, rather, shrouded in a problematic, doubtful, and sinister uncertainty -- with the law and the temple of the father not representing absolute authority, but an order viewed as disturbing and disturbed. In place of the patriarchal, Charlesworth establishes a person-centered ontology and morality of subject-object relations - a method designed to slowly eliminate the atrophied and dysfunctional values through an inventory of cultural inheritance - which replaces the absolute orders with the specific centers of our own experience. To do this, Charlesworth employs a shifting, multi-functional and experimental technique in which de-centered political and metaphysical maneuvers presume a world in which no one conceptual system can account for the full range of human experience. Once false gender myths are deconstructed and thereby eliminated, any suitable metaphor is made available for the specific requirements of the subject and the context at hand, regardless of the subject's sex. Metaphors such as the column, the snake, and the sword are thus made as readily available to women as to men, an acknowledgement that their phallic resemblance and organization of space is not the object's only significant attribute; after all, women can support like the column, shed personas as the snake sheds its skin, and be as precise as the finely sharpened blade of the sword.

Likewise, the vessel, the fruit, and the egg can be applied to men, for these objects do more than contain space or resemble the vulva and the ovaries. Men can contain space in orifices or with an embrace, nurture like the fruit, and be as emotionally and physically fragile as eggs. The concept of gender is evoked by Charlesworth only when an object resembles a specific subject's sex, or is the same as some other quality of that subject, and even then the signification of gender is only secondary to the signification of the quality shared or compared. The metaphor, therefore, remains genderless in its universal sense even though it has been associated with gender in a specific application.

This is exemplified best in Self-Portrait, an image of a round, iron cauldron surrounded by an eye, an ear, a hand, a foot and a breast carved from stone. When Charlesworth conceived the work, she was pregnant and knew intuitively how to cast herself in the iconography of somatic and psychic pregnancy. Although Charlesworth selects the round volume of the cauldron to impart the parturient condition, she does not associate the cauldron itself with a universal signification of pregnancy, as this would proscribe its use to men. Charlesworth simply equates the cauldron with roundness, and it is this roundness, in turn, that is associated with pregnancy. In both Self-Portrait and Of Myself, Charlesworth employs images of vessels - traditional object-analogies for femininity -- to convey a message of empathy with that object. Charlesworth considers it vitally important to take a symbol traditionally representing devalued femininity and turn its interpretation around to depict the symbol's strengths and utilities. In this way, Charlesworth suggests that women need not fear the employment of traditional metaphors in their art if those metaphors have propinquity to their lives.

On the other hand, should a man express affinity with the vessel as metaphor, it is as accessible to him as to any woman. By contrast, in the patriarchies of the past, though men were the privileged share holders and legislators in language, they were nonetheless, in a more limited sense than women, prisoners of the same aesthetic and moral codes established by their forbears. The total deconstruction of inherited gender prescription/proscription is Charlesworth's aim. But Charlesworth insists that she not impose her gender deconstruction on others, as this is each individual's personal, spiritual task. This is what can be called Charlesworth's Personal Religion.

In this respect, Academy of Secrets emphasizes the viability of exchange between the personal-spiritual and the cultural-historic representation. In doing so, Charlesworth effects a new visual paradigm for assigning metaphors to a subject - one based on the linguistic and semiotic manifold of language and speech (la langue et la parole). In this paradigm, language is regarded as a social institution comprised of a system of values. But it cannot exist without its flip side, that practice known as speech, defined as the individual selection and use of language. Academy of Secrets thoroughly embodies this dialectic in its visual models, in which personal contents (an individual selection and use of speech) are conscientiously selected and projected onto fields of collectively predicated object-metaphors (a cultural institution and system of values generated by language). This superimposition effects a model in which a metaphor assigned to a specific object pertains to that object alone and presumes no set pattern of relationship to other objects of the same type. This is a remarkable break from the conventional practice of habitually assigning an historically sanctioned metaphor to an object or, conversely, of projecting a new metaphor onto an object and then falsely elevating that metaphor-object relationship as a universal model.

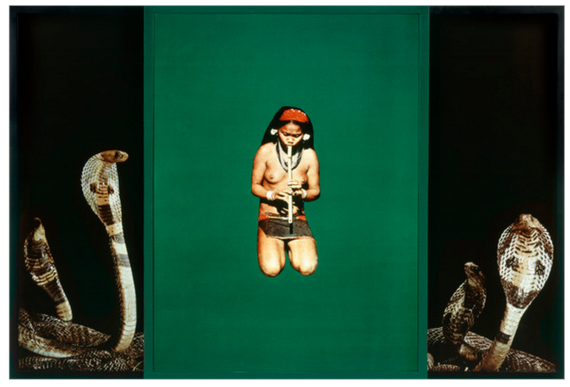

Two examples of world-pervasive systems blocking the free distribution of metaphors and treated by Charlesworth may clarify the need for a revised, epicene vocabulary. Both propagate myths of gender that -- in their classic forms -- are overly general and historically empowered by false bias and systematic repression. One of these systems originated in ancient India and influenced all subsequent religious and philosophical thought developing in the subcontinent. It is the philosophy of Tantra, the cult seeking enlightenment through ecstasy. The other system is modern, European in origin, and laid the foundation for most contemporary Western thought. It is the practice and theory of psychoanalysis, which, ironically, has become a kind of therapeutic pursuit of ecstasy through enlightenment. The two systems have more in common than one might presume, and both are significantly recalled by Charlesworth in Academy of Secrets.

Sex generates and activates the chief metaphors of Tantra. It's primal drive is modeled as the unremitting creation of nature, the perpetual parturition of life by the yoni (vulva), the "female" principle, resulting from an equally perpetual infusion of the seed by the lingam (phallus), the "male" principle, in a union of sexual delight. The sexes, in Tantra, are not seen as merely different, but opposite, and are thought to be ever striving for a unity attainable only through copulation. Here is one of the central myths of Tantra, and perhaps the one most destructive, for an understanding between the sexes is encouraged only through erotic encounters. Furthermore, gender is upheld as the incarnation of the world's polarity, thought to be transmitted through all things. All objects are, therefore, similarly thought to possess either male or female essence. This philosophy alone induced waves of repression and male dominance in Indian culture for untold millennia.

If the premiere Tantric model - 'the coitus of the world' - and all its gender metaphors were ever dismantled, Tantra's remaining spiritual and moral teachings - particularly those of Kundalini Yoga - would still afford profound beauty and inner peace. And as Tantra regards asceticism to be absurd and encourages the arousal and amplification of the senses to their highest pitch, it provides spiritually inclined individuals, even today, with an alternative to more prohibitive religions of the world. As there are benign aspects to Tantra that may be appealing and even liberating to the contemporary spiritualist, Charlesworth explores what Tantra might offer once its negative metaphors are diffused. This helps to explain why Chalersworth relayed in her BOMB interview that, "In Subtle Body, I borrowed from Tantric meditation, the progression of ascendent symbols along the body center, equaling seven centers in the body. Then I turned around and replaced them with symbols that are personally significant to me, that reflect my understanding of a physical, psychic elevation."

Charlesworth refers to Tantra's schemes in Subtle Body, with a vertical organization of seven objects delineated against a pure white field. "That's what the secrets in the title refers to," Charlesworth continued. "The secrets of higher, esoteric knowledge that are hidden beneath the common level of organized religion and mass culture. I'm talking about very esoteric knowledge which could come from any society or historical period in regard to alchemy. I view each art work, in a sense, as the alchemist might understand the transformation of matter, into something animate with psychic essence. Making an art work involves the transformation of matter, paper and materials into a process of animation or psychic elevation of material stuff."

From here Charlesworth proceeds to a direct reference to one of the most esoteric spiritualisms conceptualized and practiced: the signage of the subtle body, which refers to the "psychosomatic" or "spiritual" alignment of energy. The description is reminiscent of Kandinsky and Malevich who both claimed their pursuit of form as a spiritual catalyst that began with their introduction to modernized versions of the introspective wisdom described in the metaphysics of The Vedas of India.

"Animation, like Subtle Body, suggests a human body through the placement of different elements, in this case eight rather than seven because I give you two choices of brains--the right and left. Ascending from the most base matter, the clay pot at the bottom and then the fish, the sperm, the heart, the river. The two brains are the Indian magic wand in the shape of the crane and the clock, the logical, right brain. And then scarf at the top for the opening and the psyche. In a sense, the matter becomes more ethereal as you move up the swirling column. You're confronted with a pure abstraction and you realize on a certain level where the symbolism begins and ends. A great deal of it's brought to the piece by the viewer."

The techniques Charlesworth describes to reconfigure a metaphysic like Tantra for a disengendering of essentialist language and signage are the same as those that can be used in the disengendering of psychoanalysis. Yet in psychoanalysis the disengendering of embedded metaphors is more complex. Whether validly invoked or not, the engendered myths applied in psychoanalytic theory have a more powerful hold over the convictions of current generations in the West than does a five thousand-year-old Indian ecstasy cult. But the Western sexual biases incorporated within psychoanalytic theory originate in systems of Mediterranean knowledge nearly as antiquated, and which recent investigations have suggested also derive at least in part from continued contact between Mediterranean civilization and the civilization of the Indus Valley.

But as Charlesworth never inhabits one fixed conceptual or spiritual model for very long, in Animation, Charlesworth switches methodological gears to confront the gender metaphors of psychoanalytic theory. While Subtle Body and Animation both depict an aquatic body that courts sexual interpretation by combining traditional male and female signifiers, they simultaneously deny closure and ultimately provides an epicene subjectivity. In such an analogy, the fallacies that undermine knowledge are shown by Charlesworth to stem from an over-reliance on inherited speech. For the personal speech of our forebears is embedded throughout our shared language. It is this speech that Charlesworth intended us to examine, for it has been formed by political, moral, spiritual, and economic interests that have not only become insolvent with the erosions of time but are in large part offensive to the greater population of the world. Charlesworth therefore demonstrates that it is only through the seizure of speech itself that we establish the ascendancy of the open metaphor and assert our autonomy over both the mind and the spirit.

-- On 9/14/15 the author identified Yasuo Minagawa as the master framer who collaborated with Charlesworth on precisely matching her frames with each cibachrome hue. The original post did not acknowledge his contribution. On 9/16/15 the author named and linked this post to the preceding posts concerned with the spirituality of political activism that are named and can be accessed with the links below.

This article is part of a series of articles on artists, art and art histories that redefine spirituality today as a vital geopolitical activism in support of human rights and individual freedoms. Prior articles in the series include: Feminism Awakens In Himalayan Buddhist Art and Meditation, which publicly depicts for the first time the founding women of Buddhism; Same-Sex Marriage Is a Religious Institution Deserving Lawful Protection, a revelation of the art history supporting the history of queer marriage in early Christian communities; Egyptian Artist Wael Shawky Is Pulling the Strings of Crusade and Jihad at MoMA PS1, which identifies the historical, non-religious and political sources of terror and holy war in orthodox Islam and imperial Christianity; Sherin Neshat: Artist of the Decade, featuring Neshat's photographic and filmic allegories on the communal spirit of Iranian women bound by orthodoxy and hijab; Jack Smith And the Aesthetics of Camp in an Age of Political Correctness; a reappraisal of the spirit of hedonism in the face of social abjection; A Day Without Art in the Age of AIDS, on sublimating plague, mourning and rage in art; and Women's Mythopoetic Art, on reclaiming the politics of spiritual systems for women by artists Marina Abromavic, Louise Bourgeois, Nancy Spero, Mariko Mori, Shahzia Sikander, and Claudia Hart.

Parts of this article were conceptualized for "The New Metaphysical Art,' which appeared in the July-October, 1990 publication of the Italian art journal, Tema Celeste. Other parts appeared in "What's In A Word: The Deconstructions of Sarah Charlesworth", that appeared in the October 1990 publication of the Italian art journal, Contemporanea and reprinted as the cover feature for the Japanese art journal, Bijutsu Techo, in April 1991 as well as the 2012 Huffington Post article, Gender As Performance & Script: Reading the Art of Yvonne Rainer, Cindy Sherman, Sarah Charlesworth & Lorna Simpson After Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick & Judith Butler. Charlesworth's work is also included in relationship to The Pictures Artists in the Huffington Post article, PostPictures: A New Generation of Pictorial Structuralists is Introduced by New York's bitforms gallery.

Listen to G. Roger Denson interviewed by Brainard Carey on Yale University Radio.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on facebook.