This is Part Six of the seven-part series, XX CHROMOSOCIAL: WOMEN ARTISTS CROSS THE HOMOSOCIAL DIVIDE. See Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four and Part Five on HUFFINGTON POST.

With her 2010 photographic series, Back to Simplicity, Marina Abromavic has crossed the line. I mean the homosocial line, or the gender divide, as I call it. But this time I'm referring to the most ideologically and institutionally reinforced, yet volatile entrenchment of that divide. One that, so far as I know, no woman artist has significantly crossed in the 3,000 years that we can trace art's pedagogical and propagandistic roles in establishing, spreading, and reinforcing male-legislated gender codes.

I'm referring to the Bronze Age iconography associated with the founding of the biblical Abrahamic social code and tradition. For while the artist's iconography of withdrawal into the demure pastoral life of herders of sheep and goats in the mountains on the surface appears innocently in quest of personal renewal, it has the deepest possible allegorical roots. Roots extending through history to the semitic narrative that is the basis of the three great patriarchal faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. In this, Abramovic has mythopoetically refashioned the iconography of a 3,000-year-old tradition to suit her view of a privileged relationship with Nature established not by a patriarch, but by her own image as a woman.

If Abromavic's Back to Simplicity is ever to surface within the mainstream accompanied with a religio-centric interpretation like my own, the backlash of the orthodoxies could be scorching, even if contained and short-lived, as those aimed at artists generally are. Abramovic herself makes no claim to composing an analogy to religion with a revisionist gender-parity as her aim. But her imagery is both too familiar and too loaded even for schoolchildren to regard as anything other than an overt reference to the Axial Age founding of faiths. Even if she isn't suggesting that such a faith be founded by a woman, the mere displacement of a revered patriarchal figure by a woman is enough to incense orthodoxies. And really, what else can such a succession of images mean? In one, a woman, Abramovic, stands alone atop a mountain facing a sublime panorama of creation. Like the goat herder who became the Prophet Muhammad, she is seen wading among livestock to single out a black sheep that she carries, Christlike, on her shoulders. When she stands between two large tablet-like stones while steadying a goat (both the sheep and the goat have conventionally represented sinners), how can we not see an analogy to Moses? Finally, like Abraham, she returns to the mountain to raise a newborn lamb as her gratitude before the majesty of Nature. What can this be if not a mythopoetic retelling of the religious patriarch's epic narrative, only with the patriarch displaced.

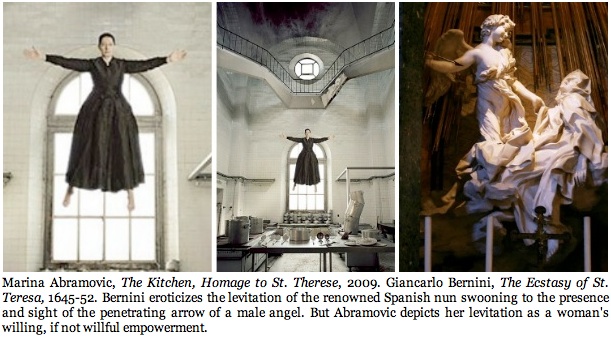

The demure reception the imagery has so far received can be attributed to Simplicity's comparative understatement relative to the artist's most mythopoetic work, created during the Balkan wars. Consider that Abramovic has in the last fifteen years been seen cleaning the meat and blood off of a great mound of animal bones (Balkan Baroque, 1997). That she has bared her breasts along with a retinue of women performers baring theirs (Balkan Erotic Epic, 2006). That she has staged her own levitation ten feet off the floor in homage to the Spanish St. Therese (The Kitchen, 2009). That she sat atop a white horse while brandishing a white flag in the manner of a modern Joan of Arc (Hero, 2001). And, perhaps most audaciously, that she choreographed and filmed a troupe of nude men mock copulating with Mother Earth (Balkan Erotic Epic, 2006). And all done in the rich media vein of mythopoetics--the making of new myths. If we consider the rich vein of feminist mythopoetics being mined by woman artists in their various attempts to restore order to a violent and rapacious world, we can see why Back to Simplicity seems little more than yet another woman's declaration of independence from the old order of male supremacy.

The difference this time is that Abramovic has pointed us to the ground zero of the Western and Middle Eastern male homosocial mythos, the hallowed foundation upon which the power structures of three millennia of civilization have been built up by means of visually disseminating the myths that reinforced the legislative right to male domination. And in taking us back to the epochs of "simplicity" by not-so-simply substituting a woman in what was simply to be a man's function as founder and leader of men, Abramovic is ironically recalling all the complexity of the homosocial mythopoetics of the Bronze and Iron Age patriarchs who, under the new military requirements of growing city and nation states, displaced and stripped whatever women held power in the earlier, smaller Paleolithic and Neolithic tribal societies.

Rare is the literature that survives to testify to this displacement of women's power, the most singular and most explicit being Aeschylus' trilogy of plays, The Oresteia. It's true that this one time a dramaturgy does no less than summarize an accumulation of myths from the dawn of the patriarchal Bronze Age--myths that over five centuries displaced the goddess and female oracle cults of old. It's also true that no one other than Aeschylus has had the audacity to stage such a scene as that of the goddess Athena mouthing her denunciation of motherhood before the scandalized citizens of Athens. Quite literally the goddess testifies that woman is not mother to a child, but merely the temporal incubation vessel for the father's seed.

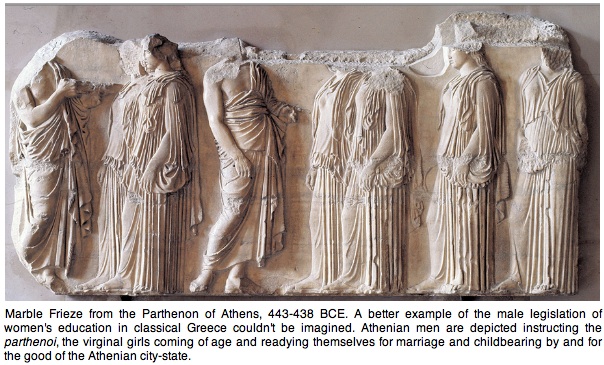

But both more forceful and plentiful than such singular literary testament are the sculptures and painted potteries that celebrate the male warrior's domination and domestication of women's homosocialization. Throughout the epochs of history, art, not literature, trace the chain of betrayal and subjugation of women through the dissemination of the male homosocial code. In this context, the entire frieze of the Parthenon--named after Athena Parthenos, the new, Bronze-Age Athena who hardly resembles the cult goddess of prehistory -- is detrimental to matriarchy in her refashioning for the male homosocial requirement of preparing adolescent girls for marriage, childbearing, and the production of soldier sons for the Athenian state.

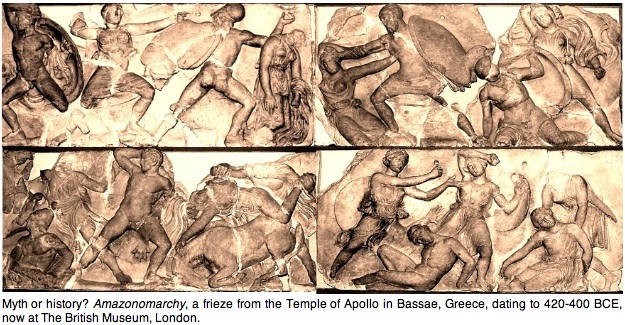

Another great frieze overseen by Iktinos, the architect of the Athenian Parthenon, comes from the frieze of the Temple of Apollo in Bassae, Greece, dating to 450 BCE. It can be seen as a mythopoetic warning to strong women and their obliging men if they ignore the example of the Parthenon and challenge men's domination. The frieze of Bassae counts, without exaggeration, among the most savage battle scenes ever rendered in art through its depiction of an amazonomarchy, a battle between the Amazon women warriors and Greek men.

The Bassae frieze is carved only a few decades after Herodotus chronicles the historical existence of warrior women who have emerged from the Black Sea to wage pitched battles against the Greeks. But by then Homer's Illiad had described the Amazon's fierceness and prowess in battle some three centuries earlier, and another battle lyricized by Peisander in 600 BCE testified to their nobility. But whether history or myth, the male homopolitical message of the mythical battles between Amazons and Greeks carved out by the sculptors of Bassae likely functioned with a more politically overarching lesson to be enforced, if not learned, by men and women of the new Iron Age. Such myths by no means alone can account for why, only with the rarest of exceptions, women of all nations did not significantly challenge the law of men for the next 2400 years. But within the history of art, such myths present a mythological iconography of male supremacy that Abramovic's Back to Simplicty can be seen challenging.

If anyone questions how myth and the conscious making of new myths that is mythopoetics could be important today, we only need look at how resistant even the most modern, scientific and technological civilization the world has ever known remains anchored to the religious and secular ideologies that the myths of 3,000 years ago helped spread. Even our secular enclaves remain ethically, politically and economically tied to male homosocial traditions and codes carved into stone during the Bronze and Iron Ages, especially those we unconsciously adhere to.

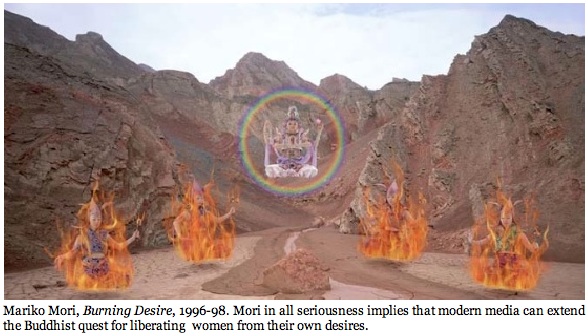

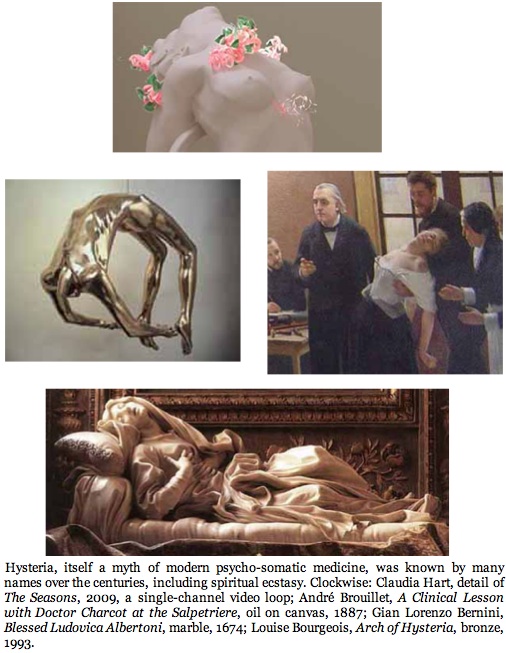

This is one reason why the dreaming of the collective mind will remain a rich study of what drives a society. For what fantasies entwine with the zeitgeist of reality to feed the myth and mythopoesy of a culture--what today comprises so much popular culture--also creeps into the polity of nations. The Hollywood and marketing machines refurbish and feed us long-established myths precisely because, as the products of our unrealized desires, they are the hooks that ensnare us over the long term. So much of mainstream entertainment, particularly the spectacular science fiction, superhero and horror genres, regurgitate the fragments of the chthonic and ancient histories of the victorious male homosociety that is not acknowledged in conventional history for being too revealing of the darker faults deep within the homosocial divide. This is the prime reason the mythopoetic unconscious of the homosocial has been sifted through over the last thirty years by artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Nancy Spero, Mariko Mori, Shahzia Sikander, and Claudia Hart. For the homosocial unconscious is an imagistic mine of protean power saturated by the belief and prejudice of the ages.

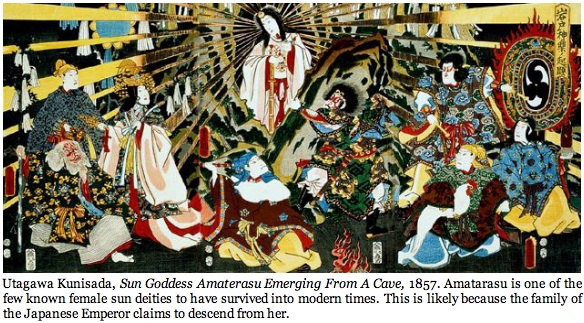

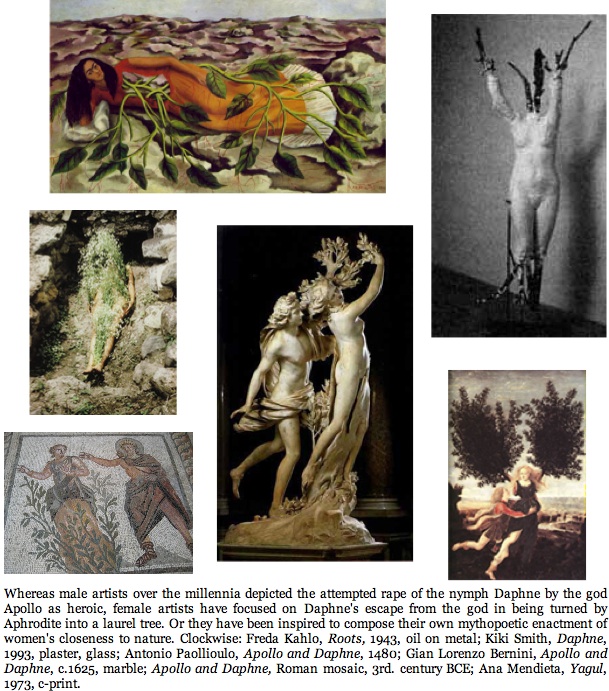

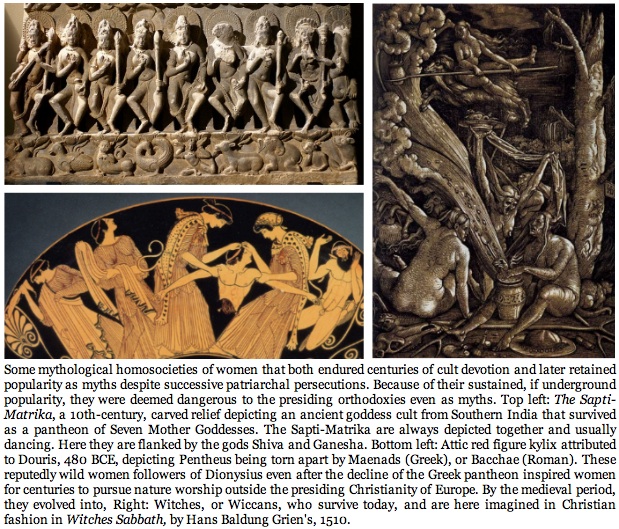

Myth, after all, is the dominant construction of a culture: the means by which social-sexual codes compose identity, reality, aesthetics, and morality, and the means by which their dynamics are played out lucidly, unambiguously, and without complication in conflicts that reflect historical confrontations. In this light, and in contrast to the mainstream dominated by the myths of the male homosocial heroes, women artists honor myths that have been in disrepute for centuries, freeing them from their muddled, ambiguous, and complicated constraints in male homosocial representations. In reprising representations of women avatars who resist the unconscious forces that historically repressed women's homosocial power in mainstream culture--an assured signal that a notoriously censorial social order is being displaced--Marina Abramovic has embraced the miracles of saints and the founders of tribal faiths that the otherwise modern secular world shuns. It's why Louise Bourgeois's art can be seen freeing the art referencing the body of Woman from the repression of millennia-old moral codes; why Shahzia Sikander recalls the tradition of miniature painting from Pakistan, India, and English colonialism, Mariko Mori the iconography of Japanese Shintoism and Buddhism, Claudia Hart the myths, fairy tales, and d'arts personae of Europe, and Nancy Spero virtually all of the above. It's not that these women want to reprise an age of superstition and pseudoscience, but that they wish to, first of all remember, then extrapolate the feminist mythologies of ancient dreams to derive from them the seeds for their own mythopoetic defiance best suited for a scientific, technological and global civilization.

They, and many artists like them, are doing much more than pioneering a revival of the traditional mythical motifs, forms, and techniques with personal visions, politics and sexuality. They are iconographically reprising and challenging the entire 3,000-year homosocial cycle by which the dominant myths reflecting the prejudice of the male victor culture of the Bronze and Iron Ages are challenged. In such cycles, history has shown that when the challenger wins, the repressed order, which was represented as monstrous, evil, dangerous women, is transformed into the new heroic order of the age.

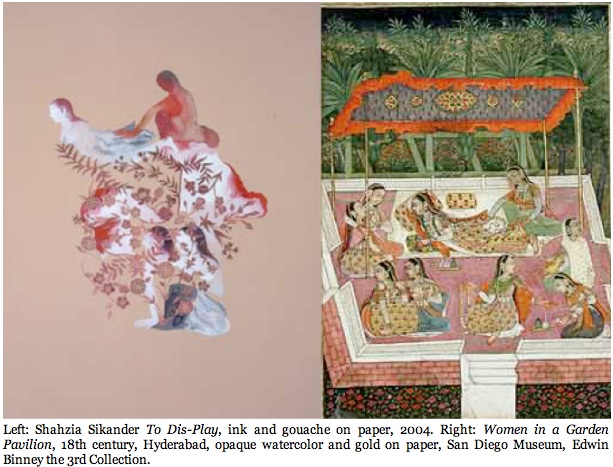

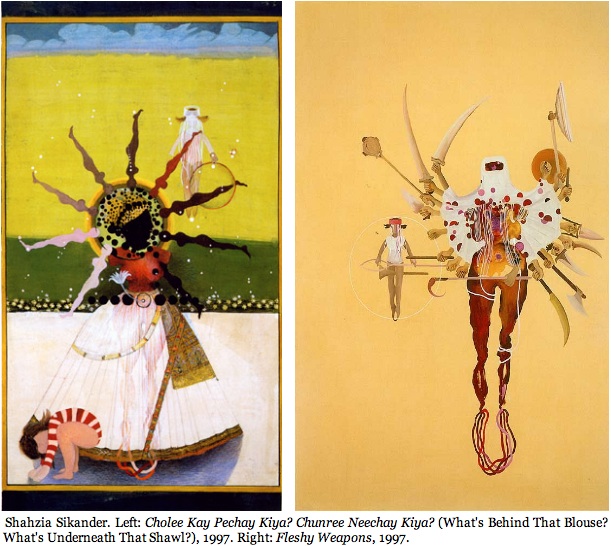

Take the Pakistani-born artist, Shahzia Sikander. Attracted by the imagery, techniques, and stylization of South Asian miniature painting from centuries past, Sikander quotes their styles, formal qualities and motifs while rescuing the medium from the misogynist and imperial tropes by which the miniature had become historically burdened. Whether leveling such competing ideologies as Hinduism and Islam or the dominance and submission of male and female homosocial orders, difference is deliquesced by Sikander in an inform of pictorial protein (literally, an elementary component of iconographic and narrative content) that, though rendered impotent amid the full-scale clash of ideologies, is employed by the artist to circumvent the codes that contribute to such conflicts before they can take root in the minds and hearts of new generations.

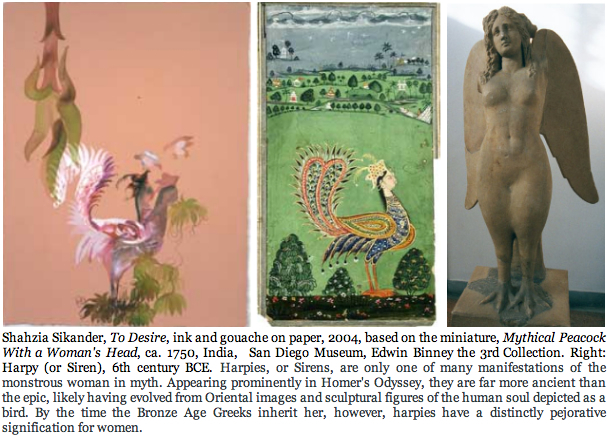

In a commission by the San Diego Museum, Sikander painted a series of gouaches on paper based on several South Asian miniatures in the museum's collection. Each enabled the artist to make visual excursions into the male homosocial courts, hunts, and gardens of the ruling dynasties whereby women were distorted into both abhorrent mythological motifs and real prisoners of male desire. The titles of the works euphemize the content of the monstrous woman in Mythical Peacock with a Woman's Head (ca. 1750); the seduction of women by divine right in Krishna Talks With Two Gopis (1719); and the sequestering of women in Mughal harems found in Women in a Garden Pavilion (ca. 1725). In painting her own versions of the miniatures, Sikander dissolves the works' misogyny into puddles of color and composition that spawn a recombinant feminine homosocial order from what remains redeemable in the 18th-century representation of women for a 21st-century feminist aesthetic. We see this in the work To Dis- Play (2004), within which Sikander literally frees the wives and concubines enclosed literally by the male homosocial vision and pictorially within the walls of Women in a Garden Pavilion.

In more expressionistic collages of appropriated motifs from Indian and Pakistani art history, Sikander reconciles oppositions in their pairing, thereby revealing the falsity of the myth that "difference is opposition." In Sikander's work from the late 1990s, we are likely to find Islamic burkas placed over the multi-armed figures evocative of such Hindu goddesses and Durga, Kali, and Neesumbasudani. Often they hover over and seem to threaten such male figures as the Mughal emperors Akbar Shah, Shah Jahangir, and Shah Jahan (though in their expressionist renderings it can be difficult to ascertain which is which without having a keen memory of their portrait miniatures). Western colonial figures have also figured into her paintings, prints, and recently her animated videos representing such British colonial entities as the East India Company, which for two-and-a-half centuries held the dominant foreign interests in the subcontinent. And yet, despite this potentially explosive recollection of histories, instead of effecting a violent clash of cultural memories in her cross-cultural assimilations, Sikander more readily affords the eager deliquescence of hostility traditionally embedded in the strict and stark separation of cultural motifs by a generation eager to get on with a more nomadic and global evolution of cultural forms.

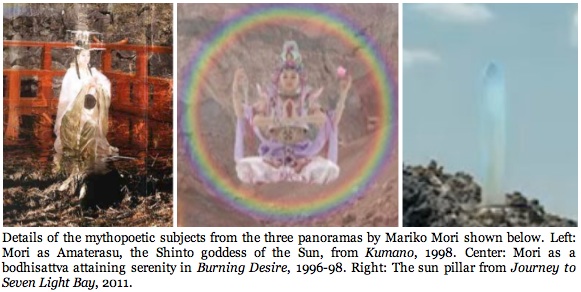

Mariko Mori, on the other hand, doesn't indict the male homosocial order quite so resoundly. Yet, like Cindy Sherman, her work cannot but be read as women's homosocial outgrowth of their separation from men. This can especially be seen when Mori portrays traditional Japanese Buddhist and Shinto personifications of nature, divinity, and cultural principles and beliefs. Invoking historical representations of female deities and animistic spirits, Mori embodies Kichijoten, the Japanese Buddhist female deity of beauty who humorously, yet self-referentially, imbues the video Nirvana, 1997-98, with it's exquisite balance and restraint.

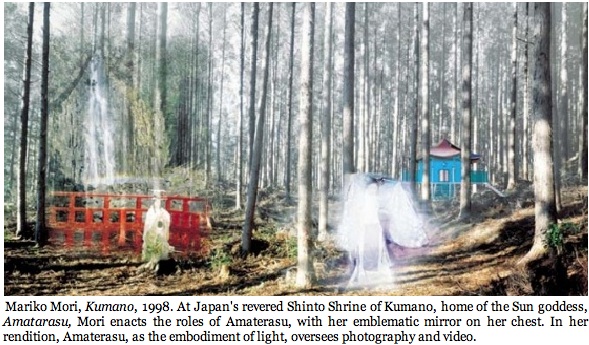

In the photographic installation Kumano, 1997-98, named for the revered Shinto shrine in the woods with its resplendent waterfalls, she becomes the Shinto sun goddess Amaterasu, bringing light to the world. But Mori contemporizes the sun deity by representing her photographically as the light upon which photography and video are indebted for their existence. A corresponding color photograph on glass depicts the Kumano woods at a moment in which the artist as Amaterasu has phased into sight standing before a red bridge and wearing her emblematic mirror (see detail image). Mori also plays a miko (a female shaman), a fairy, and an angel, all of whom in our technological age have mediumistic functions.In making such works, Mori is but the most representative of many Japanese women artists actively melding mythology, spirituality, and technology in ways that they propose advance society and nature. In the context of the homosocial, such techno-mythopoetics facilitate women's crossing of the divide to take control of the myths they've inherited as much as claiming New Media open to elaborate and serious mythopoetic productions.

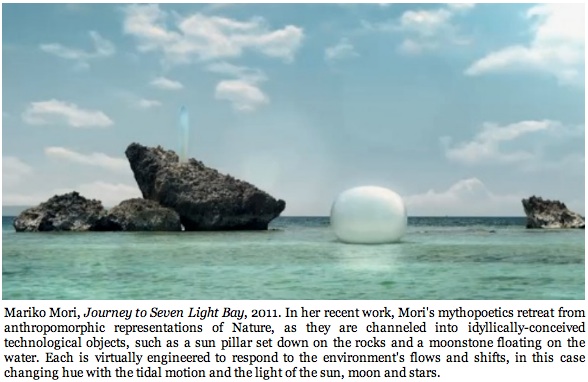

For that matter, the entire digital interface with the mythopoetic imagination becomes mythopoeticized by Mori in the body of work that she has produced since the new millennia began and can best be described as a sci-mythos in process. It is a series by which Mori's mythopoetics retreat from anthropomorphic representations of Nature to define idyllically-conceived technological objects that inhabit serene natural environments as if they are meant to represent living beings. One of the most serene, yet technically seamless works in the series is Journey to Seven Light Bay, produced in 2011. Comprised of a virtual environment that has mysteriously received the environmentally-sensitive techno-myths of a sun pillar set down on the jagged rocks and a moonstone floating on the waters. Each is virtually engineered to respond to the environment's flows and shifts, in this case changing hue with the tidal motion and the light of the sun, moon and stars. The two entities become particularly active with the solstices, whereby they change colors according to the angularities of the earth, sun and moon. It is a mythopoetic program envisioned to play a global role as Mori makes each work virtually site-specific to all the earth's continents.

Claudia Hart's mythopoetic projections also seek out serenity, but not with Mori's reticence for confrontation. In fact, Hart's mythopoetics take aim directly at 3D rampaging male avatar-shooter and -rape games in which simulation fantasies depict female avatars virtually overpowered, imprisoned and gang raped not only by male sociopath avatars, but by the millions of male gamers who operate and identify with them. I wrote in the first installment of XX Chromosocial of the respite and resilience historically found by women in their segregation from men. It is such recourse to sanctuary that informs Hart's techno universe of female avatars, in her case automatons--the legatees of Donna Haraway's feminist cyborgs and their endorsement of technological advancement (from Haraway's essay "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century")--isolated in their own alternate universes of serenity, beauty, and power.

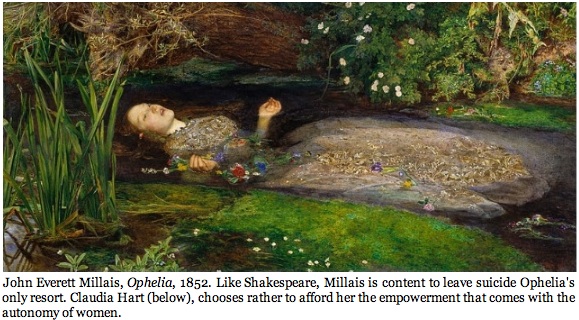

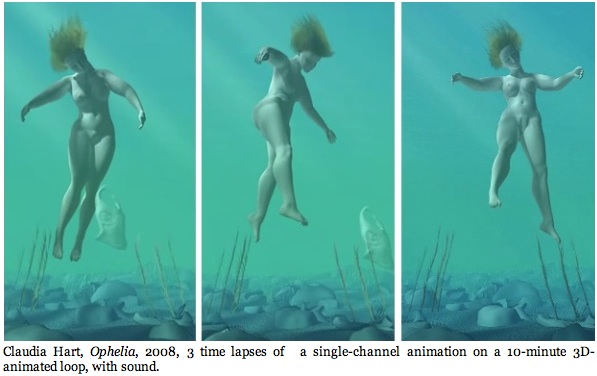

Yet, however isolationist, even solipsistic they at first seem, they have been constructed as socialized reactions to the polarized clichés of amazons and victims. In Hart's digital universe, automatons modeled after the myths of Persephone and Daphne, who flee rapist gods, and Ophelia, who suffers the neglect and abuse of a narcissistic hero, find safety and empowerment in worlds without men. But rather than depict the female myths in flight from their abusers as male artists did, Hart depicts them as automatons inhabiting clockwork sanctuaries free from male rage and rape. Hart's Ophelia, for instance, doesn't drown but evolves into a water nymph in a sea of infinite digital possibility.

Hart's digitally animated automatons seem strangely human, having an empathetic, if unemotional appearance, while remaining paradigmatic of mechanical and repetitive cycles of motion that underline their reality as animations. Seeing this disparity as their embodiment of the paradox of life conditions, Hart conceptualized her 2006-2011 series as mythopoetically personifying the unlimited variety and creation of nature while laying bare the paradoxically mechanistic yet organic patterns and forces underpinning and generating all life. In their affinity with nature (as female automatons, they can live beneath water and sprout organic growth), they are muses of Rousseau's paradise, their verdant garden metaphors holistically embodied in the sense that they acknowledge the decay that the Home and Gardens mentality discards to make room for their perpetual designer-hothouse blooms.

Attention to the postindustrial constraint of nature in fact contributes to Hart's elaboration of a pictorial mythopoetics that is something more than a Rousseauean wish for prolonged innocence. Hart's wish domains evoke what D.W. Winnicott deemed to be "transitional phenomena," the things that everyone from infants to full grown adults latch onto narcissistically to stand in for an absent person, place, or object representing security. Such transitional phenomena occupy, or are projected psychologically into a "potential space" (the overlapping space shared by two people), whereby people are free to create and enjoy illusion. Hart holds that if fairy tales are a child's transitional phenomena, art and myth are an adult's, particularly when combined in the mythopoetic--the conscious elaboration of models of life and existence that so often operate on superhuman planes to emphasize their representation of collective, if not universal, socio-political events and patterns in the world.

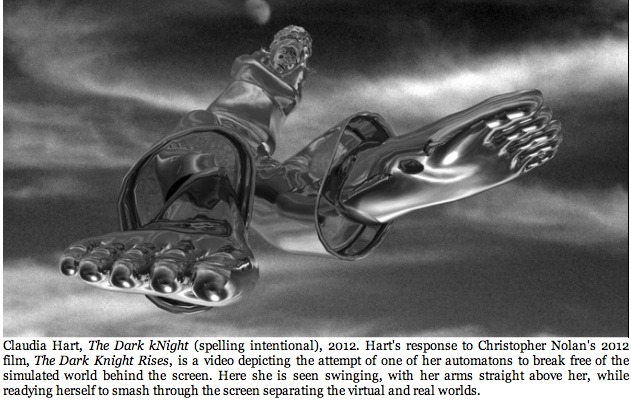

In creating Dark kNight (spelling intentional), 2012, Hart felt it was time to begin a migration out of the sanctuary cacoon of her earlier automatons. She chose to represent the attempt of a defiant automaton to break free of the simulated sanctuary world behind the screen. As the title implies, the work is Hart's response to the popular Christopher Nolan Dark Knight Rises, a film about escape from imprisonment and the powers that deem who is and isn't to be imprisoned. With the film's two highly independent, physically atheletic and defiant female characters, both of whom have escaped their own entrapments, Hart was immediately prompted to envision her own restless, racially-hybrid female avatar trying out various strategies to escape virtuality. In the video we see her hurling herself against the screen; swinging from her feet by a rope and hitting the screen full body; katapulting like a human canonball into the screen; and as seen here, swinging with a rope by her hands and hitting the screen with her feet--all seen at various speeds. Hart claims the mythological source for the figure, besides Nolan's Batman, is the chained Prometheus, bound by the Olympian gods for bringing fire to humankind. Artistically she is inspired by Michaelangelo's Dying Captives, who appear to struggle in their efforts to release themselves from their prisons of stone.

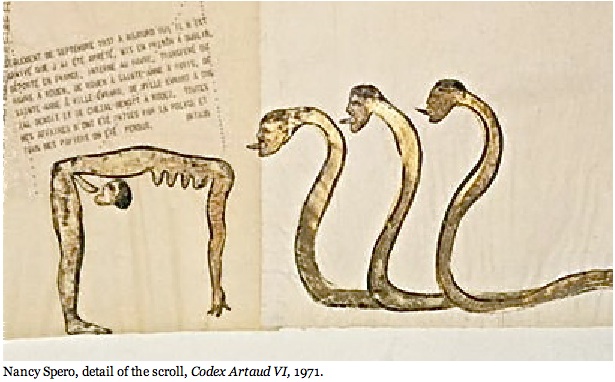

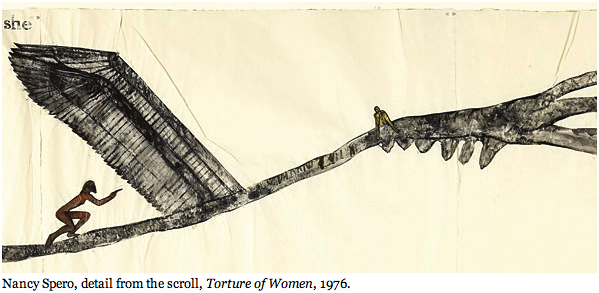

Nancy Spero is among the first feminist artists to, in the 1960s, mine both the mythopoetic and the homosocial mounds of past civilizations. The sheer volume of her representations of historical women and myths, compounded with her straddling of two generations of feminist activity (a matter in journalese of belonging to both "second" and "third" waves of feminism), illuminates what feminists have distinguished as the difference between late 20th-century essentialist identity politics/emancipation movements and the 21st-century preference for consciously constructed identity codes that we play an active role in identifying with. In other words, what was called "essential in nature" has been redefined as "inherited ideologies about nature." Strongly representing the new means for identifying what it means to be a woman, Spero's import of myth into the mainstream is analogous with the feminine imperative for power. Her figures have been described as in full command of their bodies, co-existing in nonhierarchical compositions. But I think they achieve considerably more than this. Scrolling out into monumentally-horizontal and occasionally vertical compositions, we find hand-printed and collaged armies of women athletes, goddesses, gorgons, amazons, bacchantes, priests, dancers and musicians. It's an ancient order of feminist homosociety--one predating the Iron Age that presumably ushered in the male homosocial religions, or if subsequent to the demise of the first feminist age, one that grappled with it in memory of the feminist order that went down.

Looking at Spero's work is like watching a staging of Aeschylus's Oresteia, in which the female furies rise up from the past to remind men of the power women have lost from their prehistoric existence as priests of parturition. The furies rail at the upstart god Apollo for asserting before an Athenian tribunal that women are not mothers, but merely vessels to incubate and nourish the seed of men. The furies scream out when the goddess Athena betrays all women when testifying that her birth from the head of father Zeus proves with finality that it is men, not women, who harbor creativity. If Spero echoes the female voices of three millennia and more, and if Sikander, Mori, and Hart restitute those that cried out against men's institutions since, it is because such myths summon images of an Age of Gynesis, a global XX chomosocialization feasibly predating human knowledge of paternity, essentially imagining an age without fathers, an age of Woman's Law, an age by which modern women's recall of the past restitutes the mother's place in creation. Spero's art has been enthusiastically called "women's history," but it is also emblematic of, and reprising, the mythos obliterated by men's rasping out the homosocial divide--a mythos that millennia ago was exalted for enduring, and at times triumphing over, male brutality.

Unlike the other artists discussed here, Louise Bourgeois didn't so much issue a mythopoetic or iconic oeuvre as she mined the protean forms and imagery that compose myths and icons structurally. Yet her mining of these mythopoetic fundamentals hollowed out the myths of former eras, particularly the repressive myths that reinforced male supremacy for so many centuries.

Although grounded in Surrealism, Bourgeois incised a deeper and more lacerating injury upon the sex and gender distinctions that even the Surrealists approached with discretion, largely because as heterosexual or closeted homosexual men, they were too timid to approach what we today value in queer, transgendered, and feminist dismantling of traditional models of sexuality. But in essence, Bourgeois attacks the myth of the Surrealist male at the same time she dismantles traditional male homosocial valuations of Surrealism. After all, Surrealism (with a capital S) was largely one more male homosocial enclave, at least insofar as it was men who dominated and authored the Surrealist models and manifestos issued.

Bourgeois exposes the prejudice behind the myth of the male Surrealist of the early and mid-20th-century by going back to the basic constitution of Surrealism, beginning with its principles of the inform (or pre-form)and the fetish. By extrapolating male and female genitalia and wielding them openly, instead of discreetly as did the oft-times prudish Surrealists, Bourgeois recharges the objectification of women's bodies and the homophobic exclusions of the phallus imagery that marks mid-20th century Surrealism, thereby taking Surrealism to its logical conclusion in ultimately collapsing traditionally-imposed gender and sexual representations compatible with feminism, queer and transgendered valuations that ultimately free the inform and fetish from the exclusive hetero-male valuations. In other words, Bourgeois actually achieves for all men and women what the Surrealist largely only accomplished for heterosexual men. She rendered the whole human subject and its fetishistic objectifications in one holistically destabilizing visual and conceptual ambiguity that makes all alternative readings of non-invasive sex and gender equal in the eyes of the artist.

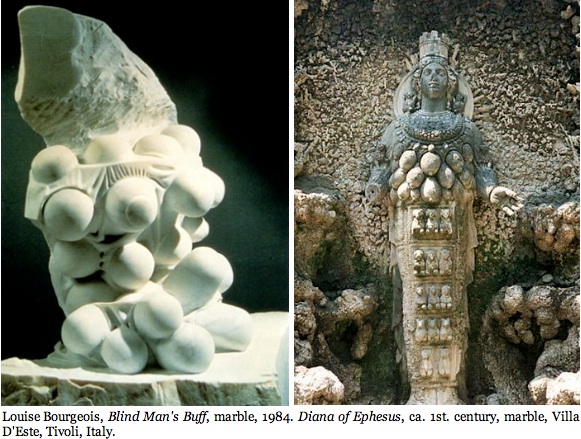

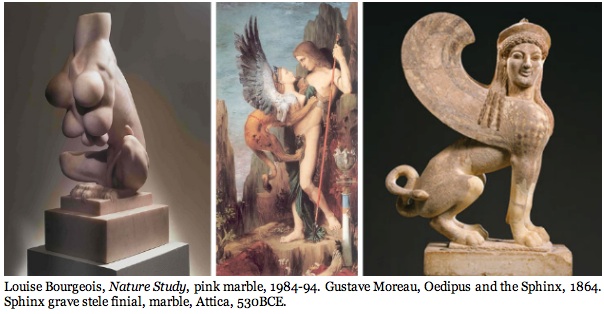

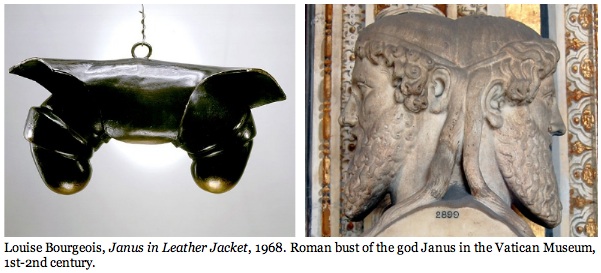

In work such as Nature Study, 1984-94, and Blind Man's Buff, 1984, Bourgeois isolates and recontextualizes the bulbous inform of the female breast that could in its isolated state, and devoid of its nipple, double as a testicle--much as they do in the fusion of such Greco-Roman with Middle Eastern mythopoetic forms as the Diana (or Artemis) of Ephesus. Or she can render a partial deliquescence by keeping the women's breasts on the mythological sphinx, but decapitate its head so to obscure whether the breasts belong to a beast that has any further sexual identification. After all, if women's breasts can be grafted onto a beast, why can't it also receive male signification? Bourgeois may not go that far with Nature Study, but she does graft two phalluses together in Janus in a Leather Jacket, 1968, an explicitly and full-fledged mythopoetic bronze cast decades ahead of its time. It's just that the mythos she "narrates" isn't a story insomuch as it is the inform, the unformed basis of a story. And with the exception of the Surrealist photographers Man Ray, Lee Miller, and Hans Bellmer, that distinction makes Bourgeoise's insight into the structural basis of myth and its impetus for mythopoetics nearly without equal.

Next: Part 7: Women Looking at Men Loving: Eve Sussman, Kathryn Bigelow and the Women Writers of Mad Men.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.