Representative George Miller is waging a lonely war against powerful enemies. He's trying to reform the 401(k) system, a system that most on Wall Street don't want reformed.

The key to Miller's plan is to force 401(k) providers to disclose their fees in plain English. His bill recently passed committee. If you don't think this is important, consider that those fees can eat up 75% of your potential retirement savings.

If you look at the system, basically what you have is working families making the conscious decision every month to try to save some money for retirement. Then along comes people managing those funds for them and they start dipping into those funds for fees that are really not in the best interest of those savers. So, you have elite financial managers getting rich off the back of middle-class working people. The last thing they really want is transparency.

- George Miller

All these fees are a mystery to both the employers and an overwhelming majority of Americans.

According to a poll sponsored by AARP, 83% of workers don't know how much they pay in such fees -- and most do not realize they pay any fees at all. To assess the toll of such fees, consider the case of a 30-year-old worker with $25,000 in a 401(k) plan. If that account earns 7% and incurs fees of 0.5% a year, without another contribution, the total payout to that worker at age 65 would be $227,000. However, if that same account incurs fees of 1.5% a year, the extra 1% would shave off $64,000, or 28%, of the payout, which would be reduced to $163,000.

Of course fees of only 1.5% is an optimistic scenario. Of the nearly $3 Trillion in 401k funds in 2007, there were $89 Billion in fees. That comes out to about 3%, not 1.5%.

Here's a list of the most common fees:

a) Management fees

b) Administrative fees

c) Distribution fees (the top three usually averaging about 1% a year)

d) Sales loads (often averaging 1.4% a year)

e) Trading costs (averaging .5-1% in an actively managed fund)

f) Excess capital gains taxes when a portfolio is turned over

The U.S. Department of Labor lists seventeen distinct 401(k) fees, including ones for record keeping, legal services and toll-free telephone numbers. Many of them are not listed in the fine print.

John Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group Inc., one of the largest mutual fund companies, said investors pay $600 billion a year in fees, an amount he called "staggering and unnecessary."

The 401(k) system has to be fixed, and I don't know anybody who can fix it but the federal government.

- John Bogle

One of Miller's top proposals is to force providers to offer a low-fee index fund. The financial industry opposes this idea.

Even if Miller manages to push his reforms through -- which is highly questionable at this point -- the major problems of the 401(k) system will remain unaddressed.

The problems with 401(k)s

With any investment there is risk. The problem is that so few 401(k) investors understand the risks they are taking on.

For instance, 401(k) money is tax-deferred, not tax-free. Therefore, by putting money into a 401(k) and getting the tax break now, you are making a bet that taxes will not be significantly higher a couple decades from now when you retire.

Will taxes be significantly higher when you retire? Unless the federal government simply defaults on its Social Security and Medicare promises then taxes will have to be raised dramatically. You can bet the trillions of pre-tax money sloshing around in 401(k)s and traditional IRA's will be at the top of the hit list.

Another risk is the systemic risk of all of those Baby-Boomers expecting to use those stocks and bonds to fund their retirement. To put it another way, starting this year and increasing every year after that for almost two decades, the number of people who were buying stocks and bonds are increasingly going to be selling those stocks and bonds (the WSJ estimates $300 Billion a year, every year).

For those of us who are decades away from retirement, that means all our investments on Wall Street are going to be coming under increasing selling pressure. What kind of return on investment (ROI) can you really expect when the number of people only selling stocks and bonds increases by several million every single year? Some say that foreign investors will snatch up those stocks and bonds, but with almost all of the industrialized world (and China) aging at the same time the concept isn't realistic.

"The 401(k) system today in the United States has been an acknowledged failure."

- Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College's Carroll School of Management.

At the end of April I was laid off from my job of 10 years.

I called up Fidelity and asked them to roll my 403(b) (the education institution version of a 401(k)) into an IRA. I was told that they couldn't do that until their employment records were updated, and those records wouldn't be updated until the "next payroll cycle."

That meant I couldn't make even this modest adjustment to my retirement savings for another month.

At the start of June I called up Fidelity again. Their records were now updated, but the money would have to be moved "manually" (whatever the hell that means). The email sitting in my inbox said that it would take "7-10 business days".

At this point it suddenly occurred to me just how illiquid my 403(b) money really was. So I began looking into this problem and found out that my experience was rather mild in comparison to some.

Even with recent gains in stocks such as Monday's, the months of market turmoil have delivered a blow to some 401(k) participants: freezing their investments in certain plans. In some cases, individual investors can't withdraw money from certain retirement-plan options. In other cases, employers are having trouble getting rid of risky investments in 401(k) plans.

As of April 28, redemption requests that had yet to be honored totaled nearly $1.1 billion, or roughly 26% of the fund's net assets. Principal doesn't anticipate that it will make any distributions to investors who have requested redemptions until late 2009 or beyond, Ms. Hale said. Meanwhile, the fund continues to fall, declining 25% in the 12 months ending April 30.

An illiquid investment is inherently risky. The people in the article above have lost 25% of their retirement savings because of that illiquidity, a heavy price to pay.

What many people don't realize is that you are supposed to be compensated for that risk. If you were a professional investor you would get higher yields for having an investment you couldn't liquidate for 5-6 weeks (as was my experience).

Instead, the average 401(k) investor gets none of the extra compensation for the risk of having probably the most illiquid investments vehicles on the market next to real estate.

To put it another way -- you are being played for a sucker.

The price of illiquidity

Earlier this year the Federal Reserve Board released a report about households borrowing from their 401(k)'s. You would think that the report would be critical of this borrowing because its potential of hurting retirement savings. You would be wrong.

More fundamentally, we find that many loan-eligible households carry relatively expensive consumer debt that could be more economically financed via 401(k) borrowing. In the aggregate, we estimate that such households could have saved as much as $5 billion in 2007 by shifting expensive consumer debt to 401(k) loans. This would translate into annual savings of about $275 per household--roughly 20 percent of their overall interest costs--with larger reductions for households that carry consumer debt at high interest rates or who hold larger 401(k) balances.

So why do households pay an extra $5 billion a year in high interest debt rather than tap their own savings? The answer is touched on later in the report.

...unlike checking accounts, 401(k) balances are generally illiquid.

Five billion dollars is no small amount, and this only applies on the losses due to households relying on high-interest debt. The more significant way you lose potential savings is by being cheated of compensation for the risk.

But how to measure it? To answer that let's look at how Wall Street views risk compensation.

One way of capturing the cost of illiquidity is through transactions costs, with less liquid assets bearing higher transactions costs (as a percent of asset value) than more liquid assets.

Most people are under the misconception that the only cost associated with a trading an asset is the brokerage transaction fee. In fact, the largest cost is "opportunity cost".

This cost can be measured by the bid-ask spread - the difference between what a buyer will pay and a seller will receive.

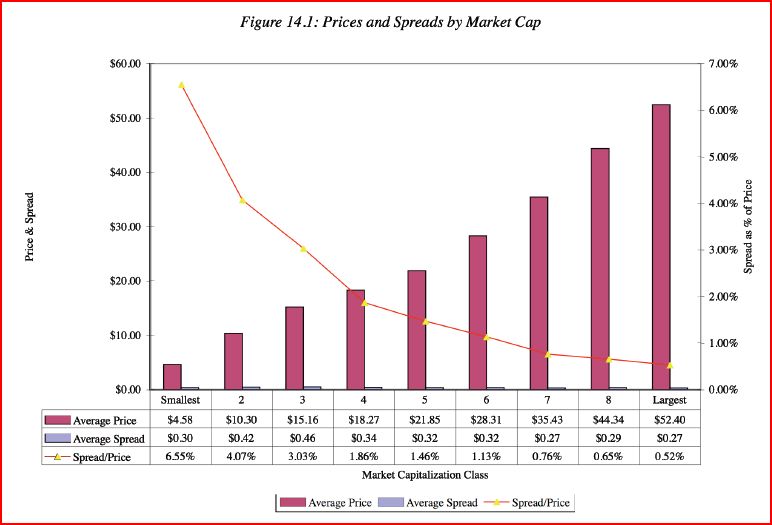

The bid-ask spread for treasury bonds, the largest and most liquid market on Earth is less than 0.1%. However, according to one study, small-cap, low-volume stocks the bid-ask spread can rise to as high as 6.55%, no small amount. Other studies have found the spread to be even greater.

To put this into perspective, an illiquid stock on Wall Street that may take several days to turn around requires risk compensation of over 6%. What about my 403(b) that took five weeks for me to liquidate? Shouldn't that garner me compensation of well over 6%?

Fidelity finally managed to move my 403(b) assets in four business days, but I had to wait four weeks for them to even start the process. Thus 84% of the illiquidity risk was carried by me. The average 401(k) investor is carrying an immense amount of risk with no compensation.

To put it another way, Wall Street brokers are offloading risk onto small 401(k) investors without compensating them for it. Since risk has a measurable price on Wall Street, you are directly subsidizing Wall Street by an amount that brokerage houses can actually put into their pockets for not having to hedge or buy insurance.

Not only is this this concept of 401(k) illiquidity not part of the reform proposals, most proposals would make it harder to liquidate your 401(k) after leaving your employer.