On the Thursday after the 2012 general election, I had a heart attack. I won't go into too much detail on the events leading up to the event, but suffice it to say that it involved weeks of volunteering, election-based events, taking care of family members, celebrating after the results were in, and working on my new non-profit organization, which is dedicated to improving health and health care in the Tampa Bay area and saving Medicare and Medicaid millions of dollars.

At first, I told my friends, it looked like "no good deed goes unpunished," but that was not completely true. It was not for the deeds that I was punished. It was my hubris and hypocrisy.

I have been involved in public health since my undergraduate days in the late 1970s, and it was no news to me that diet, exercise and familial patterns can all affect your health. The original study that verified that fact started in 1948 in Framingham, Mass. Since the study's original results were published, public health program developers have been putting out the message that health can be improved and life can be extended thorough a regimen of better diet and exercise, regardless of your family history.

So here are the two main concerns: a) How do you get the message out, and b) how do you make those impacted take action? The first part is easy, and it's been done countless numbers of times, on billboards, radio and television public service announcements (PSAs), "must-see-TV" episodes, billions of pounds of pamphlets picked up at doctors offices or health fairs and subsequently thrown away, and through hundreds of public health programs, from building community gardens to changing school lunches into meals that kids push aside and grab a snack later.

Some of these efforts have been successful, in part, and other have been a waste of funding. All because the second half of the equation (making those impacted take action) is hard.

It was hard for the man who is known as the father of public health, John Snow. He was a British physician who was trying to solve the problem of a major cholera outbreak in London in 1854. He had determined that all of the cases could be traced back to the use of certain wells in the city, so he put out the word that those wells needed to be avoided, but all of his efforts in talking to local government, speaking to the populace, putting up posters and leaflets failed. The wells were too convenient, and avoiding them too inconvenient. So the number of cases continued to climb. It was then that Dr. Snow thought "outside of the box" and stole the pump handles, forcing people to go elsewhere for their water. The number of cases dropped, and the sciences of public health and epidemiology bloomed. (Don't ask me why no one just replaced the handles. Maybe the smith who forged them had already died of cholera -- that would have been convenient to the tale.)

That may have worked for Snow and London, but getting people to take better care of themselves before that get truly ill is another matter altogether. There is no magic button, no pump handle you can steal to force the populace into healthy lifestyles.

There are two main theories behind behavior change that are commonly used in public health program development. One is the "Steps to Change," or trans-theoretical model developed by Drs. Prochaska and diClemente, and the other is the "health belief model." Put together, they essentially say that people change health-related behaviors a) when they finally believe that the change will impact their health and b) they are ready to make that change.

That is why behavior change is so hard to propagate. I, along with so many others, have been desperately trying to make people understand, believe and ready themselves for the changes that can save or change their lives for the better. But it has to be internalized, ingrained, understood... and believed.

The economics of prevention are quite clear. The average cost-benefit (savings) ratio of health prevention methods is 7:1, and clearly what American health care needs, especially Medicaid and Medicare. Spending money on true health care instead of sick care is far cheaper, and enjoying life is far better than spending time recovering or dealing with the damage and sequelae of disease.

Which brings me back to me.

I have been pushing healthy habits through my work at CDC and Departments of Health for years. It may have been easier changing sexual habits of those I help to diagnose with HIV and other STDs. In many cases the damage had been done, or at lease done to someone they had been close with, for a brief or extended time.

But I guess I wasn't listening to my own words. Sure, I suggested going out to Sweet Tomatoes instead of grazing at Golden Corral ("where they keep all of the fat people," I once heard a small girl observe). But I still hit the fast food, still kept up all the bad eating habits I have had since I started buying my own food and put on the "freshman 15" pounds eating a steady diet of Domino's pizza in college. (Don't get me started on barbecue. I forever gave up the concept of kosher laws for the love of ribs at Tunnel BarBQ in Windsor.) Exercise, proper sleep habits -- talked about, but not personally followed.

So here I am, post-heart attack one and going in for double bypass surgery to avoid heart attack two, which would be massive.

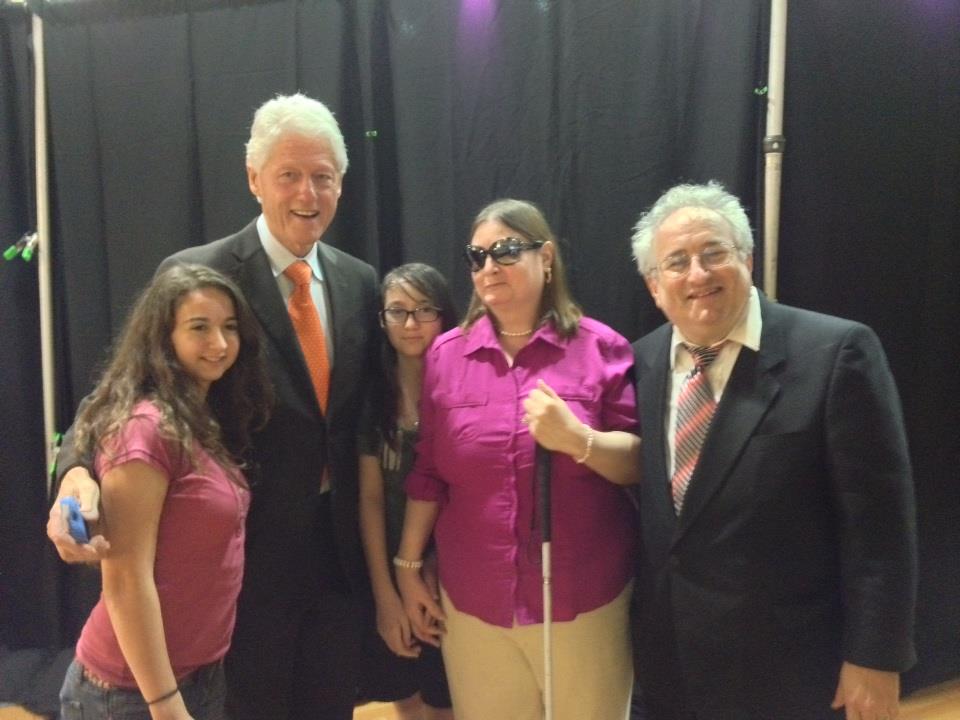

Before turning out the lights and going to sleep tonight, I took a look at my chest and reminded myself, that starting tomorrow, I will have a new scar there. However, like Steve Austin (the "$6 Million Man, not the wrestler), I will be stronger. (Now that I think of it, they never showed Steve Austin's scars, but then again, it was the '70s, and they showed Marcus Welby doing house calls. Not exactly reality TV.) Maybe I should look more at President Bill Clinton, (whom I met in person during the campaign) who essentially jump-started his post-presidential career with open-heart surgery and a healthier lifestyle. Time to start talking the talk AND walking the walk of prevention.

Night, all. Next time you see me, I will be stronger, and a force to be reckoned with.