Corruption has become the backbone of American business and politics. Whether it involves bribing elected officials through perks offered by lobbyists or using substandard materials on construction projects, someone is always looking for ways to peddle influence, cheat on materials, skim money off a contract or scam potential victims. While some people think of corruption only in terms of power and money, the corruption of basic thought processes reaches deeper into our society than ever before.

- Plagiarism has made an impressive comeback (largely due to one's ability to copy and paste text from one digital source to another).

- Electronic larceny (in the form of identity theft, phishing emails, malware viruses and worms) has become a recurrent threat to computer users.

- Sarah Palin seems hell-bent on ruining the English language while glorifying her own functional illiteracy.

- The recent scandal involving Shirley Sherrod demonstrated how lazy many media outlets have become with regard to performing due diligence and basic fact checking.

- Andrew Breitbart's scurrilous media pranks have proven that, for some political activists, the ends undoubtedly justify the means (no matter how odious their collateral damage might be).

Mark Farrell as Machiavelli (Photo by: Jay Yamada 2010)

With many Bay area theater companies, one may hope for a good evening of theater but end up being disappointed. With CentralWorks, quite the opposite happens. Even if a person arrives feeling tired, worn down or uninformed with regard to the subject of the play, it doesn't take long before that person is on the edge of his seat, totally involved in the drama unfolding before him.

CentralWorks probably sets the highest artistic standard in the Bay area for consistently intelligent, provocative and relevant drama. Gregory Scharpen's meticulous, almost cinematic soundscapes usually add an eerie undertone to the proceedings.

Last year, when CentralWorks offered the world premiere of Machiavelli's "The Prince", I was struck by the playwright's skill at making Machiavelli's treatise on the use of power so relevant to contemporary politics. My reaction was primarily with regard to the Bush administration (which had been accused by John Dilulio of being micromanaged by Karl Rove's team of "Mayberry Machiavellis".)

While Dilulio's comments caused quite a ruckus, most people had a greater familiarity with the fictional town of Mayberry than with Niccolo Machiavelli or his political treatises. As a result of his writings, Machiavelli's name has become synonymous with the use of deceitful measures in power struggles (whether they involve political intrigue or flat-out war). His writings have proven to be remarkably accurate.

CentralWorks recently revived this production, which was inspired by Machiavelli's so-called "handbook for tyrants." A year after its premiere, playwright Gary Graves seems to have grown even more prescient. As one listens to a description of the corruption and decay in Florence, one can't help but compare the playwright's references to failing infrastructure, homelessness, public apathy and the loss of a general fund to the crisis America faces today. Many of his references now seem aimed at the Obama administration (perhaps for its growing defensiveness and naive clumsiness in managing political capital).

Essentially, Machiavelli's "The Prince" involves a battle of wits between two men: the young Prince Lorenzo who has suddenly risen to great power and his former tutor (Machiavelli) who has become a master of political intrigue. The younger man is extremely idealistic, wanting to make peace with his enemies and restore Florence to its former greatness. He finds it extremely difficult to believe how cynical his former teacher has become. In his program notes, Graves explains that:

"Machiavelli was an experienced diplomat at the height of the Italian Renaissance. He visited the courts and palaces of many of the most powerful figures of his day as an emissary of the Republic of Florence. He saw first-hand how the dangerous games of power politics were played, and he began to draw a whole range of conclusions about the nature of those games in general. These conclusions, and the reasoning behind them, constitute the text of The Prince. But he wrote the book during the low point of his life.

After many years of service to the Republic, the government rather suddenly collapsed and Machiavelli was forced to leave Florence when the powerful Medici family returned to take control of the city. What followed for Machiavelli was a kind of exile, when he lived on the family farm seven miles outside Florence, reduced to a life of idleness and insignificance. It was then that he began to reflect upon his career in politics and wrote The Prince.

Most scholars agree that Machiavelli's The Prince is one of the most influential works ever written in the history of political science. Though it was composed some time around 1513, the short book wasn't actually published until five years after Machiavelli's death in 1527. The text of the book includes a dedication to Lorenzo deMedici II (the grandson of Lorenzo the Magnificent), and makes it clear that Machiavelli intended to present the work to young Lorenzo, the new Duke of Florence, as a gift. It is also fairly clear from the dedication that Machiavelli was hoping the small book would impress the new ruler enough that he might bring its author into his service.

Though we know from Machiavelli's letters that he considered trying to present the book to Lorenzo in person, there is no historical record of such a meeting ever actually taking place. Our play, however, imagines what might have happened if it did."

Cole Alexander Smith as Prince Lorenzo (Photo: Jay Yamada (2010)

That CentralWorks continues to maintain such a high level of intellectual acuity in its work is a great tribute to Graves' artistic vision and the company's collaborative process. He directs and lights many of the company's intimate productions. And, because the company performs in a tiny 50-seat space with arena seating, Graves has become a master of crafting his scripts to unheard musical rhythms (not only does he teach playwriting at the Berkeley Rep School of Theatre, since 1996 Graves has helped to develop 16 scripts for CentralWorks). There is a flow to many of his texts that pulses like chamber music. As a result, the CentralWorks experience has taken on a legacy of "total immersion theatre."

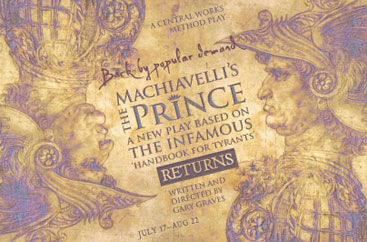

Poster Art for "Machiavelli's 'The Prince'"

It isn't often that a play challenges its audience to wrestle with so much information while the moral values of each argument are delivered with such passion and intensity. This year's revival offers a new cast, with Mark Farrell as Machiavelli and Cole Alexander Smith as the Prince. Both men offer carefully etched performances which keep the audience on edge throughout the play's 70 minutes.

The CentralWorks revival of Machiavelli''s The Prince continues through August 22nd at the Berkeley City Club.

Read more by George Heymont at My Cultural Landscape