Silent diseases are defined as those which produce no clinically obvious signs or symptoms. From high blood pressure to chlamydia, from gluten enteropathy to periodontitis, patients can go for years without being diagnosed.

Silent diseases perform slow, steady, and insidiously erosive stealth attacks on a person's autoimmune system. Some may be linked to other diseases or their diagnosis may be masked by a similarity to some other disease's symptoms. As the late, great Alberta Hunter explains in the following video clip, "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out."

Like AIDS, depression knows no boundaries. It can strike people at any age, within any ethnic group, and will not be prevented by a person's wealth, gender, religion, political beliefs, or sexual orientation. When depression paralyzes an individual emotionally, it can have a toxic effect on his family.

Several years ago, when I entered the Kaiser Permanente health system, my primary physician asked me to visit a psychiatrist to see if I was having any problems with depression. This occurred midway through the Bush administration when, in addition to some logical financial concerns, I was deeply saddened by what had been happening to our country.

I knew I was not depressed and the psychiatrist agreed. In fact, we both had a bit of a chuckle when I stressed that there is a big difference between being depressed and being lazy (some of us choose sloth as a means of curbing our workaholic tendencies). However, slothfulness should not be mistaken for depression.

In a recent edition of The Borowitz Report, comedian Andy Borowitz wrote, "With just one day until the key Republican contests in Michigan and Arizona, a new survey of likely voters indicates that in a match-up between former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney and former Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum, a majority would choose suicide over either candidate."

Depression is not just a disease of silent sadness. Sometimes the silence masks a burning, unfocused rage whose destructive power terrifies the person who bears it as a curse. The strange thing about this silence is that, while it can be used to punish those closest to the person who is depressed, it can also prevent that person from striking out and doing much greater harm by saying hateful words that can never be taken back.

* * * * * * * * * *

Ever since Dan Savage and his husband, Terry Miller, launched the "It Gets Better Project," more and more people have been talking about teen suicide and urging suicidal adolescents to contact The Trevor Project.

Long familiar to Bay area audiences from his popular book and monologue entitled Not A Genuine Black Man (the longest running solo show in the history of San Francisco theatre), Brian Copeland has returned to The Marsh in San Francisco with a new show which is not what anyone would call "a laugh and a half." Sure, there are his deft characterizations of friends with weird personalities and even weirder voices (one of which sounds exactly like the Stinky Dog from Rubber Chicken Cards).

But comedy is the flip side of tragedy. And for Copeland (a San Leandro native who has built a long and successful career as a standup comedian and television and radio talk show host), the pressures of balancing a performing career with the responsibilities of being a single father have been magnified by depressive challenges that make The Waiting Period: Laughter in the Darkness a much deeper, darker, and more desperate emotional puzzle for Brian to solve than his previous outings. There's no doubt that he has struggled to survive.

Dedicated to the memory of Colton L. Fink (a young man Copeland knew who committed suicide at the age of 15 in 2011), Copeland's show draws nervous laughter from his depiction of a single father who is so paralyzed with depression that he can't even boil spaghetti in order to serve his young children dinner. This is a man who, despite his fame as a lovable comedian, finds himself wondering what the best price might be to pay for a gun which will only ever need to fire one bullet.

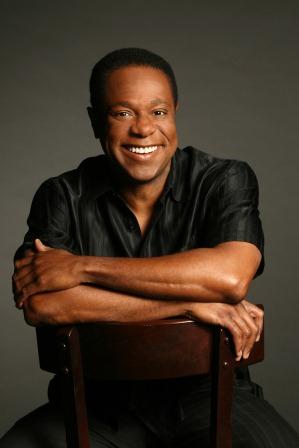

Brian Copeland (Photo by: Joan Marcus)

Occasionally, ordering in Chinese food can help Copeland' get dinner on the table. But there are other times when the brutal recognition that the people who so cheerfully ask how he is doing really don't want to know the answer to their question can lead to painful, bitter eruptions of rage.

The Waiting Game takes its title from the 10-day waiting period during which any California gun dealer must run a mandatory background check on a potential buyer. The waiting period also serves as a cooling-off period for angry minds. Theoretically, having to wait 10 days to purchase a gun may allow more rational thinking to prevail over suicidal or homicidal ideation.

If, as they say, art holds a mirror up to society, then Copeland's new monologue accomplishes much more than merely entertaining a paying audience. The Waiting Period puts very human faces on the despairing souls whose lives have been severely affected by depression. In his show, Copeland asks the audience to stop and ask themselves if they know someone who might be dealing with depression. Or if they themselves might be in need of help.

Brian Copeland (Photo by: Joan Marcus)

To show how easy it is to miss the signs that someone is in emotional pain, Copeland shares the story of how, in the depths of a major depression, he was called upon to address a school auditorium filled with students eager to meet a celebrity. When Brian realized that the young girl who had followed him to the parking lot was struggling with depression, he tried to alert a member of the faculty that one of her students desperately needed help. His attempt to sound an alarm almost met with failure because the teacher was the kind of perky personality who only wanted to hear good news.

One reason why so few people speak up about their own pain is that they are embarrassed to be labeled as a downer. Another problem with our culture is an overwhelming desire to tune out cries for help from those who are in genuine emotional distress.

For some people, depression continues to deliver an endless stream of disappointment and disillusionment as they get older. Their assessment of life is, perhaps, best summed up in this Paul Robeson recording of a popular spiritual:

To read more of George Heymont go to My Cultural Landscape