I love music documentaries. Whether they describe the intricacies of building a piano (Note By Note: The Making of Steinway L1037) or the adventures of the Los Angeles Children's Chorus on their first trip to China (Sing, China!), the process of witnessing people coming together to make music has always fascinated me.

It doesn't matter to me whether a film is about Tibetan folk songs or Klezmer music. I don't mind if it's about a group of volunteer African musicians uniting to perform Beethoven's Ninth in the Congo's capital (Kinshasa Symphony) or the electrifying Rhythm Is It! (in which Sir Simon Rattle leads a huge educational outreach project that culminates in a performance of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring by the Berlin Philharmonic along with 250 local schoolchildren and 25 dancers).

* * * * * * * * * * *

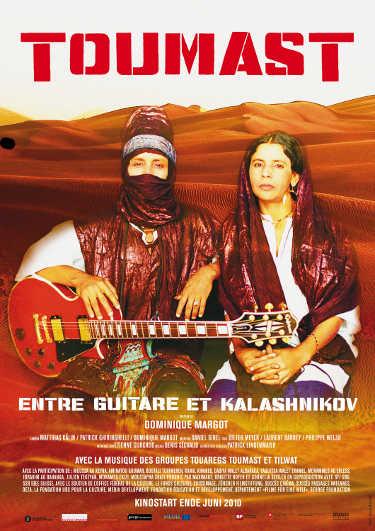

Sometimes, pairing documentaries about forms of musical expression that seem completely alien to each other produces a fascinating contrast. Suppose we start with Toumast: Between Guitars and Kalishnikovs. Beautifully filmed by Dominique Margot, it offers breathtaking Saharan landscapes while telling the story of a man torn between two identities.

Poster art for Toumast: Between Guitars and Kalishnikovs

Born as a Tuareg, Moussa Ag Keina grew up among the nomads who roam the Sahara. Over the years, political differences between countries like Mali and Niger have taken their toll on the Tuareg population and its rapidly disappearing culture.

Like many young Tuaregs, Moussa sought employment in Muammar al Gaddafi's armed forces in Libya in the 1980s. Wounded during his time spent with the Tuareg Liberation Front, he received medical treatment in France.

Disillusioned by the random bloodshed he witnessed in the Sahara (which is shown in the documentary) as well as the assassinations of 12 of his colleagues, Moussa has evolved from a rebel fighter into a rebel musician. As a Paris-based singer/guitarist (and leader of the musical ensemble named Toumast), he tries to make people more aware of the plight of Africa's Tuaregs through his concert appearances and recordings.

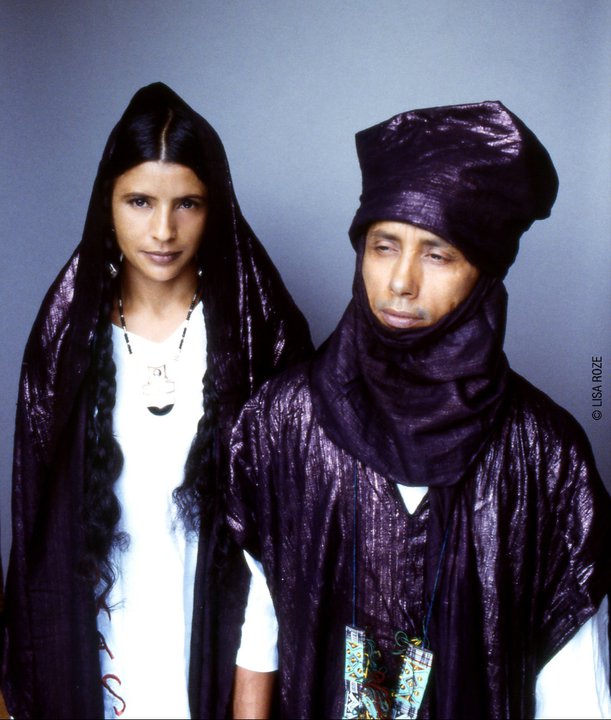

Aminatou Goumar and Moussa Ag Keina

As Margot follows her subject across the Sahara, she witnesses the emotional loyalties that tug at his heart. On one hand, Moussa identifies strongly as a Tuareg, misses the nomadic cuisine he enjoyed as a child, and anguishes over the indignities his people have suffered as a result of drought and politics. On the other hand, the temptation to return to a lifestyle which depends on Kalishnikov assault rifles is less appealing than the freedom he enjoys creating music.

Moussa's travels take him to Saharan oases (where a guest is always greeted with free water) and to Kidal, a city in Mali where he encounters a women's music ensemble named Tilwat. (In Taureg society, women are equal to men -- as a member of Toumast explains, Tuareg music cannot be created or performed without women).

Aminatou Goumar and Moussa Ag Keina

Toumast is quite different from most documentaries about contemporary musicians. Filmed against a background of political isolation and cultural alienation, it is filled with exotic images ranging from camel racing to desert sunsets. Although obviously now a French resident, more than ever Moussa feels like a man without a country. Here's the trailer:

* * * * * * * * * * *

As the San Francisco Opera prepares for this summer's new Ring cycle, I wish every politician who has ever attacked the National Endowment for the Arts could have a chance to watch Sing Faster: The Stagehands' Ring Cycle, a documentary filmed 20 years ago when the company was reviving its 1985 production of the Ring designed by John Conklin and directed by Nikolaus Lehnhoff. What they would see are real Americans doing real work as stagehands who, not surprisingly, belong to a real union.

Originally photographed in 1990 as a 30-minute film about the sets for Wagner's Ring cycle, the hour-long documentary was not completed until 1998. Filmmaker Jon Else (who submitted 137 funding proposals in the intervening years) did not enter the project as a major opera buff. As he recalls:

"My wife and I had taken our kids to see La Traviata. It was a family matinee, and they left the curtain open during one of the scene changes. It was great. The soprano finished her aria and left the stage. Then all of the sudden 100 workers came out and transformed a palace into a cornfield or a cornfield into a palace -- I can't remember what it was.

I approached the San Francisco Opera to see if we could do a little behind-the-scenes movie about the scene changes, and they said sure. And then we both forgot about it. About six months later they called me back and said we're doing the Ring cycle, do you want to do the Ring cycle? And I, without thinking, said sure (never having heard the Ring cycle). I went out and got a recording of it and sat down and listened to it. I thought: Are they kidding? People actually listen to this shit? I can't imagine people actually paying money to listen to this garbage. And then slowly it began to grow on me. It is certainly an acquired taste. By the time we finished shooting, I was a complete maniac for the Ring cycle."

Viewers who are devout opera fans -- or were lucky enough to experience this particular production -- will be particularly impressed with the backstage action in high pressure moments during actual set changes (as well as the card games that take place backstage during long periods of singing). Hearing the stagehands' version of the complicated plot -- "Doesn't one of the giants get a chick out of the deal, too?" -- provides some unexpected laughs.

Because the entire film was shot during rehearsals, Else was able to bolt an Arriflex camera to the balcony rail of San Francisco's War Memorial Opera House. Using an intervalometer, the camera was automatically triggered to expose one frame every 20 seconds for two months. The resulting blizzard of images was edited into two fascinating stop-motion sequences. The first compresses two months of set construction into two minutes. The second squeezes the entire 17 hours of Wagner's Ring cycle into one minute.

What Else's documentary really captures is a labor of love for the operatic art form supporting the massive collaborative effort required to mount a Ring cycle. As he explains:

"I've always been really interested in working people. I've done a lot of work. I've worked in factories and I've worked in construction. I'm just fascinated by the work that people do. Old fashioned work. Drive a nail, push a wheelbarrow, work. The thing that attracted me originally was the grandeur of the sets. Then I began to hang out with the guys who did this astonishing work.

I was really struck by two things. One, just the amazing skill and intricacy involved. They're almost like musicians the way they move, the way they choreograph, the way they can have several huge sets moving on the stage at the same time -- all in silence. The second was how well they knew the operas. I don't know why that should have surprised me, but it did. What is easy to miss when you watch the film is that it is in a deafening sound environment. You have a 106-piece orchestra playing full volume and you often have people whispering in the foreground."

Sing Faster is available on Netflix and can also be viewed in six 10-minute segments on YouTube. Here's the first segment:

To read more of George Heymont go to My Cultural Landscape