Whenever I visit the San Francisco Conservatory of Music I'm surrounded by gifted young students on a clearly-defined career path aimed at becoming a professional musician. Most of them come from upper middle class families who are able to underwrite such an intensely focused chapter of their higher education.

While many films about music concentrate on adult performers, few zero in on the challenges facing the family of a child prodigy. Vitus (Fredi Murer's enthralling film about a Swiss child piano prodigy who begins to study encyclopedias at the age of five) is one of those rare films that celebrates prepubescent intelligence. Equally adept at math and music -- with a mental acuity far beyond what most grade-school educators can even begin to teach -- the young Vitus, who desperately wishes to enjoy a normal childhood, uses his fierce intellect to take control of his life.

Luckily for Vitus, his family can afford to nurture his talent and has enough social connections to clear most obstacles from his path. But what about the talented children who are born into poverty and must rely on the arts as a means of escape from a life in the slums? What happens to them?

* * * * * * * *

Beadie Finzi's ballet documentary, Only When I Dance, is the kind of film that has the audience on the verge of tears throughout most of its 78 minutes as it follows two poor Brazilian ballet students in their quest to escape the slums of Rio de Janiero. The film's producer, Giorgia Lo Savio, stresses that:

"Dance is such an integral part of Brazilian culture and the Brazilians are actually renowned for classical ballet. The Municipal Theatre in Rio (the equivalent of the Royal Opera, London) is huge and Brazil has produced some big international stars. Thiago Soares is currently a principal soloist at the Royal Ballet. However ballet is still seen as an exclusive art form, only accessible to the white, wealthy elite. There is a huge contrast between rich and poor. Ballet is reflective of this divide.

Initially, Irlan's parents were concerned about his passion because classical ballet is not seen as a suitable career for a boy (especially not one from the favela). We actually had to give up on the first boy that we found because his family was very resentful and ashamed of the fact that he was doing ballet. They didn't want any part in it. But with Irlan, we arrived at a point when his family had come to terms with it and were very supportive, which is unusual."

Irlan Santos da Silva

The two young dancers (Irlan Santos da Silva and Isabela Coracy) were discovered by former ballerina Mariza Estrella, who founded the Centro de Dança Rio in 1973 and helped to guide them toward international competitions. While Irlan's talent is obvious, the dark color of Isabela's skin and the fact that, by professional ballet standards, she needs to lose some weight, are factors working against her.

Isabela Coracy

Unlike many ballet documentaries, filming in Rio's favelas was rife with danger. As Giorgia Lo Savio explains:

"In order to access the favela we had to pay a 'contribution,' which was going to be used for the schools. We were a conspicuous presence and, although we had permission to be there, there were certain areas where we were not allowed to film due to the ongoing drug trade. We weren't allowed to roam freely. Every morning we would be met outside the favela by the 'associate' -- the man who liaised with the drug traffickers on our behalf and granted us access. He would come and pick us up in his car (or meet us with his little scooter) and we would follow him. His presence protected us by providing assurance that we had permission to be there."

"Filming in Rio was very tough," confesses director Finzi.

"You can't just get out of the van and shoot where you want, what you want. The threat of violence, of theft, is huge. The standing joke was, whenever I asked 'Can I shoot that?' the driver would answer 'No, you'll get shot at.' The problem is that the threat is so high and so consistent that you become quite blasé. It is a real effort to remember that, as director, you are responsible for a whole crew and their safety. You are constantly torn between wanting to get a certain shot versus considering whether it is worth taking the personal risk involved in getting it. In the end, we did get through the year but not before a few hair-raising incidents in the favelas."

What sets this documentary apart from so many other ballet films is the genuine struggle of Irlan and Isabela's parents to help their children realize their dreams. The heat of the streets in Rio's Complexo do Alemão is a far cry from the calm of Lausanne, Switzerland, where Irlan's first impression of Europeans is that "Everyone is so polite!" His joy at seeing snowflakes for the first time in his life is matched by the determination visible in his classical and contemporary performances in the following two clips:

Only When I Dance has the kind of artistic vision, dancer's discipline, compelling characters, and financial urgency that help to shape a great documentary. As director Beadie Finzi notes:

"The key to most good documentaries is capturing a moment of change or transition. This story had some fantastic ingredients: two kids on the cusp of adulthood trying to realize an impossible dream where the difference between success and failure would mean everything. But it was also a tough sell (set in Brazil, shot in Portuguese, a ballet documentary), all pretty niche. However the more I examined the story, the more the universal themes shone through -- themes of race, class, and the sheer determination and love of family -- which I knew could translate to anyone, anywhere.

At first, I was quite intimidated by the language barrier. I had never made a film entirely in a foreign language. But my co-producer, Christina Daniels, was a fantastic collaborator. She was my ears and my mouth. We worked very closely and quietly together on location. I would brief her with questions and she would relay these to the characters. Occasionally I completely misunderstood the sense of a conversation, but most of the time I could follow the debate. In a strange way it taught me to watch in a different way -- to really look at my characters and listen to their inflection. I think I also was able to maintain a little more distance (not a bad thing since I was also shooting and recording sound on location)."

Unlike Bertrand Norman's 2006 documentary, Ballerina (which concentrates on the training of prima ballerinas at the Vaganova Ballet Academy in St. Petersburg), Beadie's film is focused squarely on two dancers from poor families who, against all odds, are reaching for the stars. You'll want to have lots of tissues on hand when you see this film.

The good news is that Irlan was accepted into American Ballet Theatre's studio company, ABT II. In a recent interview, he stated:

"My family and I were very surprised at first that someone wanted to do a documentary about me. We really didn't quite understand what it would involve. So, in the morning when there were cameras on me getting dressed, going to the bus stop, it was a bit of a shock. One of the favorite parts in the film for me are the scenes where I am seen working so hard on the choreography for the Nijinsky ballet. I remember how hard I worked to prepare that piece for Lausanne. When I saw my hard work captured in the film, it brought tears to my eyes. I only recently watched myself in the film, so it is all very new and strange to me. The film is a very honest representation of what I went through in the last couple of years."

Here's the trailer:

* * * * * * * *

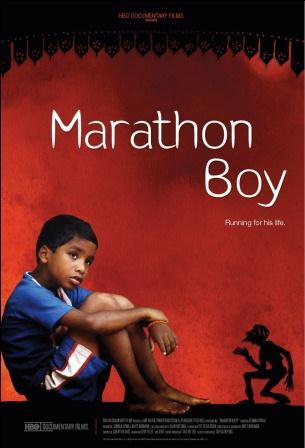

Recently seen at the 54th San Francisco International Film Festival, Gemma Atwal's powerful documentary, Marathon Boy, follows the real-life story of a young boy born into poverty in one of Bhubaneswar's slums in Eastern India. Abused and beaten by his father (an alcoholic beggar), when he was only three-years-old, Budhia Singh was sold to a street hawker by his mother. Budhia subsequently came under the care of a judo coach (Biranchi Das) who ran an orphanage for children from the slums.

One day, as a punishment for his cursing and unruly behavior, Biranchi Das instructed Budhia to run around the block. When he returned five hours later, the young boy was still running.

With a keen eye for an extraordinary talent, Biranchi Das decided to train Budhia Singh to become a marathon runner. His ultimate goal? To enter the boy in the Olympics. This link will take you to a 13-minute news segment that was filmed in the early days of Budhia's saga.

Not only do the protein supplements and training Budhia receives from his mentor help to build his stamina, by the time he is four years old Budhia has run in 48 full marathons and become an inspiration to India's poor. Meanwhile, Biranchi Das has done a remarkable job of manipulating the media to transform Budhia into an unlikely superstar.

Budhia Singh running in a marathon

By the time Budhia has been entered into a 42-mile run, India's Child Welfare Committee is threatening to take his newly-adopted son away from Biranchi Das. Some accuse the judo coach of cruelty to a minor and of using Budhia to further his own gain. Meanwhile, the biological mother who initially sold Budhia to a stranger is developing a new interest in the funds supposedly donated to a foundation to help support Budhia's athletic future. After she accuses Biranchi Das of torture, he is arrested. Budhia is kidnapped and returned to his mother to live in the slums.

What follows is a media frenzy as Biranchi Das accuses the Minister of Child Welfare of wanting control over Budhia. Although Biranchi Das is acquitted and released from jail, he is eventually murdered by a gangster in a mafia-style hit job. Budhia ends up as a scholarship student in a private school but, on weekends, he must return to his home in the slums. As director Gemma Atwal explains:

"With this type of story, ethical considerations were paramount. At the height of his fame, Budhia was only four years old, and a very small child doesn't have a sense of self, or a sense of 'I.' Often Budhia would repeat phrases learned by rote, about how he loves to run and there's nothing more special than this. I was keen to make it understood to the viewer that he was being fed these phrases and thoughts by those around him. I couldn't help but feel enormously protective over Budhia, with whom I came to form a very close bond and who referred to me as 'didi,' meaning 'sister.' There was one point when I became quite passionately vocal against what was happening. I felt that Budhia was being pushed too hard and for the first time the anguish was clearly visible on his face. It was towards the end of his record 42-mile run. I wanted Biranchi to stop the run. I shouted to him to take a good look at his son. I ended up turning off the camera, even though as a filmmaker it felt valuable to record observationally what was occurring here. It was a personal decision. The impulse to intervene was stronger than to observe. Deep down I knew that whether I was filming there or not, Budhia would still have been running. Such was the power of the Indian media, who were very much active players in the duo's story and directly shaped the duo's fate."

Budhia Singh

"Definitely, after so many years, you end up caring very deeply for those you film with. You become increasingly aware that you are the steward of someone else's story and you have an ethical obligation to deliver an accurate and honestly told story that reflects the full measure of an individual. What struck me very early on was the different perceptions out there regarding the boy's coach, Biranchi Das. In the West, we know him because of Budhia and he's largely painted as this two-dimensional, black and white pantomime villain, whereas on the ground in Orissa, he's the hero of the slums, the Good Samaritan, the man who rescued Budhia from the oppression and anonymity of poverty. There was rarely a time when I'd turn up at the judo hall and there wouldn't be some damsel in distress or a line of people there to solicit Biranchi's help in some dispute or with medical bills. And he would never turn anyone away, he would always help. You can't help but admire this. So my approach evolved and I began to see both Budhia and Biranchi as the main subjects of the film. In many ways, Budhia is the vehicle into the story while Biranchi is the main driving force behind it. The story becomes just as much about this poor man living in a flawed society who's trying to make a difference and do good things. It's his search for meaning in a world that seems ruthless and chaotic."

Poster art for Marathon Boy

Atwal makes excellent use of archival footage from news outlets to show the ongoing political struggles between Biranchi Das and government bureaucrats. Her film starts off as a feel-good story of a coach/benefactor rescuing a child with a specific talent from a life of poverty and then careens into the wild legal and media circus swirling around Budhia Singh. As the story progresses, however, it becomes obvious how interdependent the coach and his runner have become.

At present, no trailer is available for Marathon Boy. When one is eventually released, you'll be able to find it here. However, since HBO has provided substantial funding to the project, you can expect that it will eventually be shown on that channel and released to DVD. Atwal's film may not be your typical sports documentary, but it tells a riveting story through an unflinching lens.

To read more of George Heymont go to My Cultural Landscape