Additional Research by Albert Gould

Last week, Louisiana opened 86 percent of state waters to recreational fishing, shrimping and crabbing. This opening extends to three miles offshore and was greeted with understandable relief by state anglers, marina facilities, charter boat guides and any business that caters to the recreational fishing industry. Louisiana has been hit hard on all fronts as a result of the catastrophic explosion at the BP-owned Macondo well in the Mississippi Canyon oil field on April 20. But, should more questions be asked in the aftermath of hearings last week by Barbara Mikulski's Senate Subcommittee on Appropriations, combined with charges today by the watchdog Louisiana Bucket Brigade that public health is being shorted by the EPA?

Are air and water quality monitoring efforts along the Gulf Coast all that they should be?

We received a tip from a fisherman buddy on the Gulf who suggested we take a look at the minutes of the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission (LWFC) for June 3. Our friend was wondering whether lost revenue might be the real reason LWFC opened the waters. The answer was "yes, " and found on page one. Louisiana Department of Fish and Wildlife (LDWF) Secretary Robert Barham also suggested that a visual inspection for oil was enough if oil was not present for seven days.

To keep an area closed was counterproductive since the Department operates on revenue generated from the sale of licenses and fees associated with outdoor activities. Even though the public may be saying they are not seeing any oil, Secretary Barham knew staff did a good job in finding where oil was located.

In the next paragraph, the minutes quote Barham discussing the possible hazards associated with the dispersant Corexit, which has been used in unprecedented amounts both sub sea and at the surface to mitigate the appearance and quantity of oil. BP has used more than 1.8 million gallons of Corexit in the Gulf since the catastrophe began in April, angering environmentalists, scientists and Gulf Coast residents over the potential for long-term public health consequences.

Barham said that BP has not been forthcoming with information requested by LWFC, and has not responded to "several letters written to them (BP)." Commissioner Patrick Morrow asked if biologists looked for surface oil and "subsurface oil" combined with dispersants and whether BP or the manufacturer of Corexit, NALCO, provided a protocol "that can be followed to determine the effects of Corexit" on the fish.

Secretary Barham stated that the company only has given the information that can be obtained from the Internet. They have not given the Department a complete list of ingredients with the percentages. The challenge was determining the effects of the dispersant mixed with raw oil in a sub sea environment. Another challenge was to ensure safety by doing tissue analysis on the fish.

So, we can say that a Louisiana state agency, tasked with the protection of public health and monitoring of the waterways, is relying upon information available on the Internet to assist in determining whether fish caught by recreational anglers is safe for consumption.

There has been no tissue analysis completed by the FDA or NOAA prior to the opening of the waters within the three-mile limit. Barhum stated that he relied "heavily" on the Office of Fisheries staff, but that NOAA only provided initial contacts about oil impacts.

Are the waters off the coast of Louisiana clear of public health hazards? Or was the opening of recreational fishing due to pressure from the recreational industry as well as the specter of lost income? The end result is that sport fishermen may be relying upon a visual inspection of the water and a smell test.

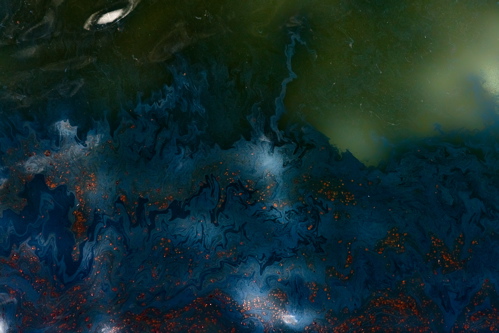

West Side of Pier-Wide Shot Copyright June 7, 2010 Nick Zantop

Above and Below: Water and Oil Under and Around the Pier Grand Isle State Park, LA Copyright

Nick Zantop

Is it acceptable for recreational anglers, but not Grandma in Iowa, to consume seafood from previously closed fishing grounds on the Louisiana coast? For a comparison of commercial and recreational closures look here.

LDWF does not seem to know the answer either, and no answers are forthcoming from NOAA, BP, the EPA, or FDA.

Governor Bobby Jindal appointed Barham as the Secretary of the State's Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. The Louisiana Legislature created the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) as part of an Executive Reorganization Act. The role of the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission (LWFC) is one of policy-making.

Part of the Internet information on dispersants LDWF might rely upon can be found in an April article by the independent, non-profit journalism organization, ProPublica.

Once they are dispersed, the tiny droplets of oil are more likely to sink or remain suspended in deep water rather than floating to the surface and collecting in a continuous slick. Dispersed oil can spread quickly in three directions instead of two and is more easily dissipated by waves and turbulence that break it up further and help many of its most toxic hydrocarbons evaporate.

But the dispersed oil can also collect on the seabed, where it becomes food for microscopic organisms at the bottom of the food chain and eventually winds up in shellfish and other organisms. The evaporation process can also concentrate the toxic compounds left behind, particularly oil-derived compounds called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs.

The Louisiana estuaries are the nurseries for developing shellfish.

NOAA has declared fish outside the three-mile limit fit for market, but admits that fish caught within the three-mile limit cannot go to market because the product has not been properly tested.

In a transcript from Senate hearings last week Larry Robinson, the Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere, was grilled by Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-Maryland).

Robinson said, "Research on the effectiveness and effects of dispersants and dispersed oil has been underway for more than three decades, but vital gaps still exist," adding, "chemical dispersants can be an effective tool in the response strategy, but like all methods involve tradeoffs in terms of effectiveness and potential for collateral impacts."

Here is where the devil enters the details.

At the sea surface, early life-stages of fish and shellfish are much more sensitive than juveniles or adults to dispersants and dispersed oil. There are no data on the toxicity of dispersed oil to deep-sea marine life at any stage, so we have to extrapolate based on existing knowledge. However, at both the surface and sub-surface, modeling and monitoring is confirming that dispersed oil concentrations decline rapidly with distance from the wellhead as it mixes with seawater and moves with the currents away from the treated areas.

NOAA has been conducting chemical analysis of seafood collected after the Deepwater Horizon incident. Seafood samples consisting of fin fish and oysters are analyzed for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or PAHs, Madam Chairman, to measure uptake of these compounds present in oil by marine species. To date, none of the seafood samples analyzed for these compounds have concentrations that exceed EPA and FDA guidelines, ensuring seafood reaching the marketplace is safe to eat.

But according to Robinson, "Thus far, we haven't found any evidence of these contaminants in any of the species that we've taken outside of the contaminated area."

The tests have been conducted to identify dispersed oil, not Corexit, and the Louisiana shoreline is certainly contaminated with both. Mikulski went on to ask what agency oversees state waters. Was it the FDA?

ROBINSON: That's correct. Right. And so FDA works with the states to ensure -- to help ensure that fish doesn't reach the marketplace that's taken within the three-mile limit that's contaminated with any of these products. And we provide any assistance that they need in that process.

Even if oil is the only worry, do fish swim outside of the "contaminated area?" What about the obviously oiled waters within the three-mile limit that have been declared open for recreational users who pay all of those license fees?

NOAA is also relying upon extrapolated data, and not hard data, on the affected species. That responsibility for monitoring falls to the State of Louisiana and there are a lot of questions about who is behind oversight there.

Governor Bobby Jindal says in a press release that the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries has already sent the FDA " a proposed plan to open the same areas that the Commission approved for recreational fishing. In fact, LDWF has provided the FDA with input and testing samples that are awaiting the FDA labs to be reviewed. The LWFC passed a resolution urging the FDA to review the testing samples that are sitting in their labs and we support that resolution so we can open commercial fishing quickly in the areas where it is safe."

Where are the results? Is there a baseline for sampling?

FDA procedures include "baseline testing of seafood in oil-free areas for future comparisons; surveillance testing to ensure that seafood from areas near to closed fisheries are not contaminated; testing as part of the re-opening protocol to determine whether an area is producing seafood safe for consumption; and market testing to ensure that the closures are keeping contaminated food off the market."

Testing involves two steps, including both a sensory and a chemical analysis of fish and shellfish.

In June, Michael R. Taylor, J.D., Deputy Commissioner for Foods at the FDA testified that NOAA and not the FDA is looking at bioaccumulation of dispersants.

The current science does not suggest that dispersants bioaccumulate in seafood. NOAA, however, is conducting studies to look at that issue. FDA will be closely reviewing the results of those studies. If the studies provide new information, that will be taken into consideration in management of the effects of the spill, with regard to seafood safety.

But Louisiana is looking to the FDA for answers within state waters.

Jindal emphasized the 12,260 commercial fishing licenses in Louisiana and over 1,500 seafood dealers/processors and brokers who rely on the industry. This is a compassionate response, but what about the unknown, untested and unverified public health consequences?

Anne Rolfes, Founding Director of the watchdog group, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, also testified before the Senate Subcommittee. Rolfes decried the lack of information on dispersants, saying the lack of clear scientific data mandates that "there be no assurances of safety by any party, especially the EPA, NOAA, other government bodies or BP."

I am concerned about the effect the lack of information about dispersants has on NOAA's ability to track and test for them. How, for instance, is NOAA going to track dispersants through the currents and water column, especially below the surface. How can the federal government ask these questions when they can't even get and/or share basic safety information about the dispersants being used?

Rolfes' organization also took aim today at the EPA for incomplete data on air quality monitoring.

A new analysis of the Environmental Protection Agency's BP oil spill air monitoring reveals that the EPA monitoring network, while unprecedented in its scope, has still fallen short of documenting exposure in Louisiana in the days since the oil spill.

The review of EPA's sampling examined monitoring that took place from the time of the spill until July 10th. Results from benzene, hydrogen sulfide and particulate matter sampling were compared to health standards. LABB cited troubling reports of hydrogen sulfide in Venice as well as repeatedly high benzene readings throughout the region. The review found that sampling for particulate matter 2.5 - small airborne particles known to aggravate the respiratory system - should be enhanced.

While the EPA says pollution levels are "good" to "moderate" and "unhealthy for sensitive groups" at worst, Rolfes insists there has been no baseline to determine what is "normal" for the monitoring sites.

There is some data being collected about some of the better known VOCs (volatile organic carbons) and compounds that are classified as "IDLH" -- Immediate Danger to Life and Health. The EPA released a new database on the popular document-sharing network Socrata this week, but LABB criticizes local data sampling as being inadequate.

Bottom line? No one knows for certain what are "safe" levels of dispersants, oil, and VOCs in the air and water. There was no baseline to begin with, agencies are overlapping or not doing their jobs, and there are still 80 days worth of oil and dispersants in the Gulf to contend with.

Note: The oil photos are for perspective. The only adjustments made in Photoshop to these are tone, contrast, and levels corrections to adjust the image to better represent how it looked in real life and to eliminate the glare of the sun. Nothing has been added or subtracted from these photos. (Nick Zantop)

Cross posted with OEN News