No.

It is a word that every person confronts. Absolutely everyone -- CEOs, entrepreneurs, artists, celebrities, even the president -- gets "no" for an answer. And it is a word that most people -- whether novices or seasoned professionals -- dread because "no" is a word that can easily seem like death to a dream.

"No" looms over everyone's life, and it is universally met with trepidation and fear because the value of being told "no" is so little understood. And yet there is great value to getting "no" for an answer because it is a word that can point us in the right direction. It is a word that motivates us to do something differently, try something else, get better, innovate, keep going.

In fact, sometimes "no" can be the best answer to get.

I should know.

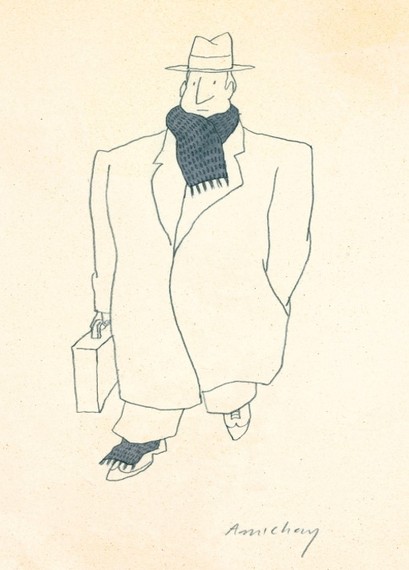

In my own career in advertising as partner at Israel's leading agency Shalmor Avnon Amichay / Y&R, and in the arts as a cartoonist, I have realized that "noes" -- whether from colleagues, from clients, from life, or from within -- have great power and are simply directions on the map to "yes."

To begin to see this in your own life, you have to see that "noes" rarely end with an exclamation point. Rather, "noes" usually end with an invisible comma that will point you in the direction to "yes." An excellent example from my own career is the odyssey of "noes" I confronted to get my first cartoon published in The New Yorker.

In 1989 while a student at the Bezalel School of Art in Israel I came to New York to study for a year at the School of Visual Arts. Paul Peter Porges was my teacher and a published cartoonist for MAD Magazine and The New Yorker. The dream of every cartoonist in the world is to have their cartoons published in The New Yorker. That was my dream too.

"There are so many magazines and newspapers. Why do you insist on The New Yorker?" Paul asked me. "It's impossible to get in... only the top cartoonists make it. You have no chance!"

"But if you insist," he continued, "You should know that on every Wednesday you can leave an envelope with sketches at The New Yorker reception desk, and you can have them back on Friday."

I didn't need more than that. I drew all day and all night. On Wednesday morning, I walked all the way to The New Yorker and went up to the 22nd floor.

The receptionist gave me "the look." The "I've seen thousands like you" kind of look. Funny, I gave him exactly the same look, "and I've seen thousands like you." Then he stuck my envelope into a huge box full of envelopes.

On Thursday I hardly slept.

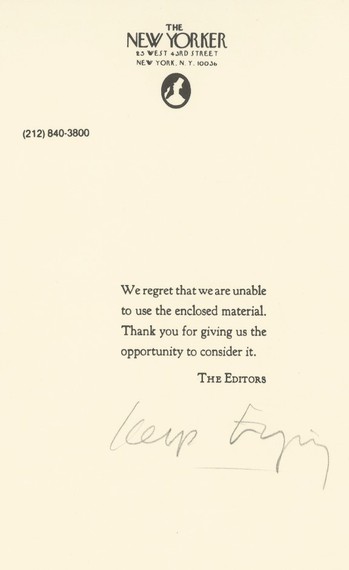

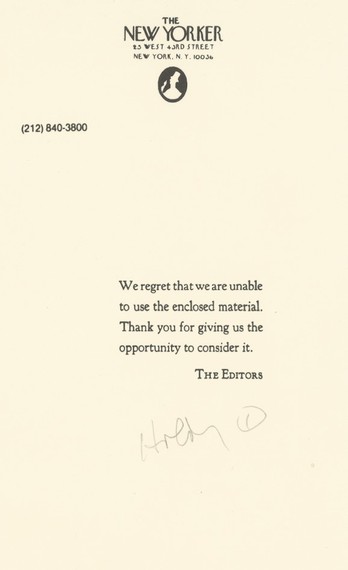

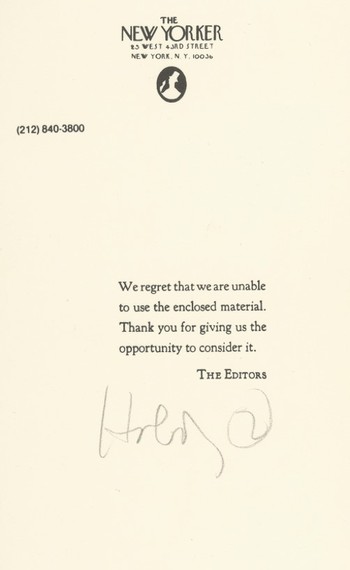

On Friday, full of excitement, I rushed to The New Yorker office. My envelope was waiting for me. All the sketches were in it, and in the same order. There was a yellow note from The New Yorker attached to it that read, "We regret that we are unable to use the enclosed material. Thank you for giving us the opportunity to consider it. -- The Editors."

In other words, "No."

On Monday, I showed the note to Paul. He said, "I told you so."

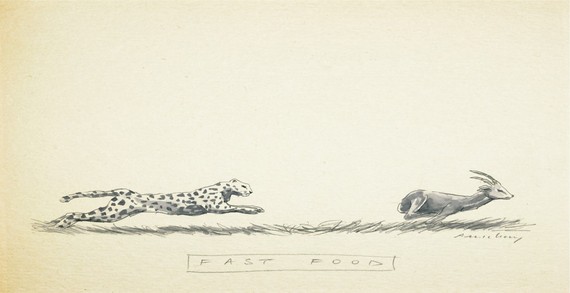

Having my cartoons published in The New Yorker was my dream, so I went all over the city with my sketch book, drawing more and more sketches. On the following Wednesday, I -- along with one envelope and 20 sketches -- went to The New Yorker office again.

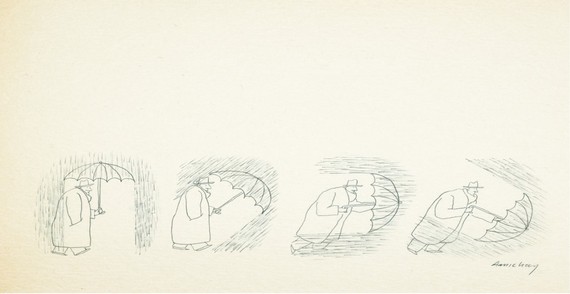

Here is a sketch from that envelope:

On Friday another "no" yellow note was waiting for me. Wednesday and Friday. Wednesday and Friday. Wednesday and Friday. It went on and on. Then one Friday there was a surprise. It was the same "no" yellow note, but there was a scribble on it.

I couldn't read it. It was illegible. I asked the receptionist, but he couldn't read it either.

On Monday, Paul was so happy. "That scribble means someone is telling you you're on the right track."

The note said, "Sorry."

A scribble? It was a masterpiece!

Wednesdays... Fridays... sketches...

...and scribbles, this time one that read, "Keep trying."

You see I could read it now. Another week went by, another 20 sketches.

Then, one Friday, one drawing was missing. The pencil scribble said, "Holding 1."

What did that mean? Paul knew the answer. "The cartoon editor is keeping one sketch for the editorial meeting." Keeping or not keeping, my excitement kept on for exactly one week.

On the next Friday, I received my envelope with 21 drawings. 20 plus one, having returned the one they had held.

Wednesdays and Friday. Fridays and Wednesdays. Sketches and notes. Notes and sketches, this time with the scribble that read, "Holding 2."

After one year and 1,000 sketches, I had to go back to Israel to present my graduation project. I turned the top 10 best sketches I had submitted to The New Yorker into final drawings and presented those.

Next, I started on my long career in advertising.

Fast forward to 1993.

Commercial TV had just been introduced in Israel and I was sent by my agency to New York for two weeks. Getting ready to pack, I opened the closet where I kept my winter clothes. I was searching for my scarf and gloves and there it was, the envelope with the sketches from my graduation project.

My dream was alive again.

"I've got nothing to lose!" I told myself. I put the envelope with the final drawings I had used in my graduation project in my suitcase and flew to New York. On Wednesday I walked all the way to The New Yorker, straight to the top floor to drop them off. There was a new receptionist, but he gave me the same old look.

On Thursday I got a voicemail. It was the sweetest voice I had ever heard:

"Hi Gideon, this is Ann from The New Yorker. Could you drop by our office tomorrow? We would like to discuss some of your drawings."

"Wooooooooooow!!!"

The next day, I saw the receptionist again. For the first time ever, I walked through the castle gates.

I met Françoise Mouly, the art editor, in her office at The New Yorker. All my sketches were leaning against the wall and she said, "We would like to buy that one," which was my first color drawing published in The New Yorker in 1995, "...and we would also like to buy that one," which was my second drawing, also published in 1995.

The whole experience of being told "no" over and over and over again was how I initially began to arrive at the wisdom that every "no" is not the end of the world. I began to see that every "no" does not end with a big exclamation point -- "No!"

Rather, most "noes" end with an invisible comma --"no," -- that points the way to "yes."

Take a look at my "noes" from The New Yorker.

My first "no" was a standard "no."

Then I got a very personal no comma, "Sorry," followed by no comma, "Keep trying," followed by no comma, "Holding 1," followed by no comma, "Holding 2."

Each one directing me, encouraging me, driving me in the right direction because they pointed me to the eventual, "yes." If I had taken the initial "no" as a "No!" I wouldn't have kept on submitting.

To find the eventual "yes," you have to see the "noes" in your life as ending with an invisible comma, and then examine, explore and discover which no comma you are dealing with.

There are many types of no commas.

The first is the dramatic no comma which drives us to work even harder, such as no comma, "keep trying."

Then we have the inspirational no comma which makes us rethink, such as the no comma that tells you that you need to reevaluate what you're doing and how you're doing it.

Finally there's the most challenging no comma which leads us to change and go in a new direction, such as the no comma that tells you that you have been doing the wrong thing altogether and need to do something different.

In my career in advertising, I might hear, no comma, "we don't have the time," or no comma, "we don't have the budget," or, no comma, "can we see another option?" Most of the ad campaigns my partners and I at Shalmor Avnon Amichay / Y&R won international awards for started off as one of the above no commas. Not seeing them as ending with exclamation points but rather with invisible commas we were led to the "yeses" that would eventually win us Cannes Lions and Clios.

I see no commas as a treasure. I have developed a relationship with "no." I hug it. I embrace it. I nurture it. I care for it. I have even grown to love it. That's because getting "no" for an answer is a form of resistance, and resistance in creativity, in innovation, in art, in your career or in your personal life is great. Resistance in the form of "noes" drive us to get better, to reassess what we've been doing, to go in a better direction.

For me, "no" is a sign -- a green light and not a red light. I see "no" as simply the beginning of a "yes."

You cannot avoid "noes" in life, but if you can see the invisible comma behind them you will find the eventual Yes.