NASA is preparing an important decision about the future of manned spaceflight. The agency is expected to announce which firm(s) will receive funding under the final phase of the Commercial Crew Program. Commercial Crew is a follow-on to the extremely successful Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program which produced two private vehicles (SpaceX and Orbital) that now ferry supplies to the space station.

Following the guidance of Augustine Commission on Human Spaceflight, the White House has pursued the path toward privatization of routine space transportation. Unfortunately, NASA is under congressional budgetary and political pressure to reduce the number of Commercial Crew participants from the current three: SpaceX, Boeing, and Sierra Nevada Corporation (SNC). The underfunded Commercial Crew program gets around $400 million a year. This is small potatoes in the manned spaceflight arena and each firm receives only a portion of what is left after administrative costs.

A panel at last week's SPACE 2014 conference in San Diego offered a visual representation of this situation. The government's pork barrel manned spaceflight program, known as Space Launch System (SLS), was represented by three officials taking up half the table, while the three private industry participants shared the other half of the table. However, even this unbalanced arrangement failed to adequately portray the obscene imbalance in allocation between the public and private sectors. At a ratio of $3 Billion to $400 million the commercial folks should have squeezed into a single chair.

Framed in the topsy-turvy world of military-industrial-complex thinking, the focus of the discussion was on how the private sector could be supported if it met NASA's needs. It is as though the reason for supporting a market economy is to deliver services to a government agency, rather than seeing the purpose of the agency as fostering economic growth that will generate jobs and taxable revenues in its sector. Imagine the state of air travel if the FAA built the aircraft and treated private firms as its vassals. I suspect it would look a lot like Amtrak, but with more accidents.

It is exactly this sort of zero-sum thinking that has kept NASA budgets stuck at about the same nominal level for decades ($15- $17billion) while inflation has whittled away at their real value. Despite doing amazing research and being America's most popular agency, NASA has fallen from 5 percent of the federal budget to far less than half a percent. I love Mars rovers and cool space stations as much as any baby boomer, but the harsh reality is that with our chronic budget deficits and soaring entitlement obligations America cannot afford a space program whose mission is to boost national prestige or serve as a white-collar jobs program. To justify its existence NASA must drive the private sector forward in space, not the other way round.

To be fair, NASA is not generally to blame. Charlie Bolden and other NASA administrators have been very supportive of the President's bold call for commercialization. Oddly, it has been primarily Republican members of Congress, pandering to the NASA employees and contractors in their districts that keep the socialized space gravy train running. Senator Shelby of Alabama, whose state holds the center cut of space-pork, the rocket assembly plants in Huntsville where the giant NASA toys are constructed, has primarily driven the push for SLS.

The truly sad thing is that while a lot of folks are eager to build giant government rockets, nobody is backing a destination for SLS. The hot potato keeps passing from one astronomic destination to another. The public wants to go to Mars, but the government can't really afford that. NASA wants to visit a small asteroid, but nobody is inspired. We've been to the moon. And so, SLS remains a space solution in search of a problem. This lack of mission makes it a potential competitor for the same private firms the government has meagerly assisted.

These commercial entrants are all very promising. Boeing has methodically completed 18 of their 20 benchmarks under the program. SpaceX has already flown a number of Dragon capsules under the cargo resupply program and could probably fly a man in it, if NASA would let them. SNC's Dream Chaser has also completed about 90 percent of their program and flown several captive carry and one glide test. Meanwhile, the government's Orion capsule is scheduled for an uncrewed test launch on an expensive Delta Heavy rocket -- because the SLS launch vehicle isn't ready -- that will likely cost more than the entire annual Commercial Crew budget.

After starving the Commercial Crew program for years, Congressional advocates of governmental solutions can claim its behind schedule (just like SLS and every NASA program since 1970) and suggest further reductions or concentration of the award to a single vendor. This of course, represents a complete failure to understand the purpose of building a competitive private market that will test a number of technological models for their efficiency before settling on a dominant design.

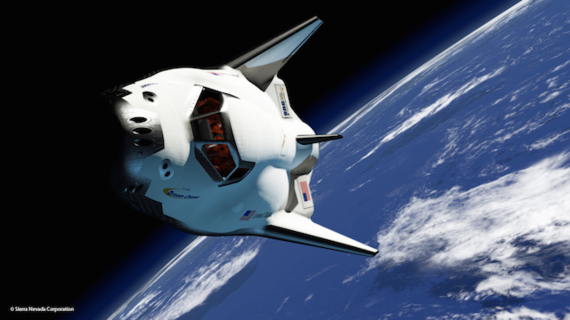

NASA's Orion, Boeing's CST-100 and SpaceX's curiously named Dragon V2 (what were they thinking?) are all capsules in the general mold of the Apollo craft of the 1960s. Dream Chaser on the other hand follows in the wake of the winged Space Shuttle and it's predecessors the HL-20 and project DynaSoar. The debate between capsules and spaceplanes is far from settled.

Dream Chaser is a beautiful vehicle that has been in the works for more than a decade. The winged design is a common feature among the promising sub-orbital space tourism vehicles from XCOR and Virgin Galactic. In fact, before SNC acquired the vehicle, I made a significant personal investment in a company that had planned to use Dream Chaser for tourism. While that firm regrettably failed with the death of its founder and my investment evaporated, I did have the opportunity to sit in on design reviews and discuss the vehicle with engineers and the former Space Shuttle commander who had planned to fly it. The Dream Chaser has also used less NASA money than its competitors and attracted positive attention from the European Space Agency.

All three commercial efforts should be funded. However, if the program must be reduced, it should be noted that both SpaceX and SNC are committed to pursuing a private market in space regardless of NASA support. Boeing's panel representative expressed a lack of interest in continuing without government funding and in a cynical attempt to prod Congress the firm publicly announced looming layoffs. Professional investors only bet on teams that truly believe in their future returns and never on firms for which outside investment is the only goal. NASA must begin to think like an investor in America's future.

--

Greg Autry is as an Adjunct Professor of Entrepreneurship with the The Lloyd Greif Center for Entrepreneurial Studies at the Marshall School of Business at the University of Southern California. He recently co-authored a report for the FAA Offices of Commercial Space Transportation entitled An Analysis of the Competitive Advantage of the United States of America in Commercial Human Orbital Spaceflight Markets. You can find him on Facebook.