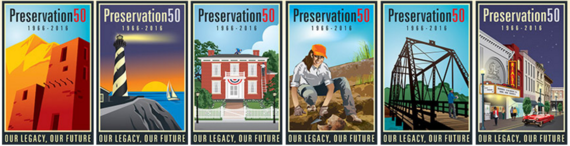

During 2016 the United States is commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the federal historic preservation program, created when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) into law. This year-long celebration has been dubbed Preservation50. It has united an unprecedented coalition of citizens who care about preservation and community to take stock of the past fifty years of preservation lessons and look towards shaping the next half decade. Americans are also choosing their 45th president, in an unusually historic and dramatic election. So what are the records of the leading candidates on preserving history itself?

There is a surprisingly close association between American presidents and historic preservation. Thomas Jefferson is often called the Father of American Archaeology for his excavation of Indian mounds at Monticello in 1782, and his home and the University of Virginia that he founded are now World Heritage Sites. In 1858 George Washington's home at Mount Vernon was the site of the first national preservation effort when the Mount Vernon Ladies Association formed in response to the estate's poor condition. South Carolina socialite, Louise Dalton Bird Cunningham, traveling up the Potomac by steamer, was horrified by the neglect and approaching destruction of Mount Vernon, and wrote, "If the men of America have seen fit to allow the home of its most respected hero to go to ruin, why can't the women of America band together to save it?"

The influence of American presidents on the nation's historic treasures has been felt since that time, particularly after Theodore Roosevelt signed the 1906 Antiquities Act into law. This legislation protected the archaeological relics in the West that recalled the thriving cultures of the first Americans, like the cliff dwellings of Colorado, Utah, and Arizona. It also allowed presidents to create National Monuments to protect places as diverse and significant to our past as Fort McHenry, Harriet Tubman's Underground Railroad, and Cesar Chavez's Forty Acres. TR's distant cousin FDR went on to sign the Historic Sites Act of 1935, which established the National Historic Landmarks program and the Historic American Building Survey. By far the greatest impact on America's historic and cultural resources, however, came with the 1966 passage of the NHPA.

Birth of the Federal Historic Preservation Program

The NHPA was a response to the well-intentioned but destructive effects of federal programs like urban renewal and the interstate highway system. It created a National Register of Historic Places, and historic preservation offices in every state. It also established a process for reviewing projects that involve federal money, land, or permits to ensure their impacts on historic buildings, sites, districts, structures, and objects are considered and addressed. In most cases, agreements are reached to lessen the impacts or even positively benefit affected historic and cultural resources.

For the first time, a program was in place to comprehensively identify, evaluate, protect, and enhance the Nation's rich cultural heritage. In practice, the effect of this legislation cannot be overstated. Today the National Register of Historic Places includes more than 1.7 million resources in more than 89,000 listings. Federal consultation about the impacts to historic sites happens approximately 140,000 times a year. Over 2,100 historic districts provide dynamic places for people to live and work. Millions of visitors from around the world enjoy iconic places such as Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, the French Quarter of New Orleans, prehistoric effigy mounds in Iowa, the Alamo in San Antonio, the Spanish missions of California, Martin Luther King, Jr.'s church in Atlanta, and the Iolani Palace in Honolulu.

The American people took the NHPA's call to action to heart in the last half-century, transforming their neighborhoods from coast to coast and generating widespread economic and social impacts. Countless studies show that the NHPA helps stabilize neighborhoods and downtowns, contributes to public education and public health, attracts investment, creates jobs, generates tax revenues, supports small business and affordable housing, combats blight and powers America's heritage tourism industry. Historic places, from private homes to community landmarks to archaeological sites to historic military bases and national parks, also maintain community pride and identity, and aid local and regional economies through their operation and maintenance.

Choosing the Preservationist In Chief

Let's be clear: when it comes to an election featuring a possible contested convention, several potential "firsts," and the epithet "short-fingered vulgarian," few voters will have cultural heritage protection foremost on their mind when they enter the voting booth. None of the leading candidates have position statements on the topic on their campaign websites. No one should expect Donald Trump to threaten to expose Heidi Cruz for her secret commitment to cultural heritage protection.

On the other hand, preservationists do constitute a sizable and untapped constituency. A recent study by the National Trust for Historic Preservation identified 15 million active local preservationists, nearly the total number of people who voted in the 2008 Democratic primary. At least 50 million Americans, or 15% of the total US population, are deeply sympathetic to the cause of historic preservation.

Without a doubt, there are significant stakes in this election for cultural heritage protection, and events over the last several years show that elected officials play an outsized role in determining whether the policy environment for preservation is favorable. Here are three key questions voters might ask the presidential candidates:

- Leadership. Will you appoint officials who will make cultural heritage preservation a priority domestically and internationally? The Department of Interior plays a primary role, including through the National Park Service, which manages almost 100,000 heritage sites. Within the Department of Agriculture, the Forest Service conserves nearly 350,000 cultural heritage sites. The independent Advisory Council on Historic Preservation advises the President and Congress and oversees the protective planning process. On the international leadership front, will you support international cultural organizations like UNESCO? The State Department and Homeland Security are positioned to confront the scourge of the black market antiquities trade, a major funding source for international terrorism.

- Funding Support. Will you ask Congress to fully fund and permanently authorize the Historic Preservation Fund (HPF)? The HPF supports the work of preservation offices across all U.S. states, territories, and the District of Columbia, and 165 American Indian tribes. Year after year, presidents request a fraction of the $150 million authorized by Congress 37 years ago, and Congress appropriates even less. For context, the annual direct investment in protecting our past has been less than 20% of the cost of a single $337 million dollar F35C Navy jet.

- Incentives for Private Investment. Will you stand up for the federal historic rehabilitation tax credit? The tax credits have helped create 2.3 million jobs, saved 38,700 historic structures, and attracted106 billion in private investments. The cosponsorship list on the Historic Tax Credit Improvement Act, H.R. 3846, includes everyone from liberal James McGovern of Massachusetts to Freedom Caucus member Ted Poe of Texas, evidencing broad bipartisan support for historic preservation in Congress. Attempts to eliminate tax credits are a periodic threat, however.

If past is prologue, we can predict how this year's leading candidates will support cultural heritage preservation from the Oval Office. Primary popular vote totals to date are as follows: Hillary Clinton (8,924,920), Donald Trump (7,811,245 votes), Bernie Sanders (6,398,4202), and Ted Cruz (5,732,220). Let's take a look.

Hillary Clinton

Several elements of Hillary Clinton's record suggest that she would be a robust supporter of cultural heritage protection. As First Lady, Hillary Clinton initiated and served as Founding Chair of the Save America's Treasures program, a national effort to match federal funds to private donations to preserve and restore historic items and sites, including the flag that inspired The Star Spangled Banner. The program awarded $315,152,000 to 1,287 grants to federal state, local, and tribal government entities and nonprofit organizations. While the program is still authorized, Congress currently does not fund it, but for a period of time under Clinton's leadership the effort shone brightly.

While First Lady, Clinton oversaw the restoration of the White House's Blue Room to be historically authentic to the period of James Monroe and the Map Room to its appearance during World War II. In 2000, she wrote An Invitation to the White House: At Home with History, a coffee table book that describes life at the White House, including the renovation and refurbishments, and directed all sales proceeds to the White House Historical Association. Funding for the Historic Preservation Fund doubled during her husband Bill Clinton's administration.

Secretary of State Clinton championed the Ambassador's Fund for Cultural Preservation, which since its creation by Congress in 2001 has demonstrated America's respect for the world's cultural heritage by supporting more than 640 projects in over 100 countries. She also visited 112 countries during her tenure, making her the most widely traveled secretary of state. Many of those visits included tours of the host countries' flagship cultural heritage sites, where one might presume her appreciation grew for the role that such places play in diplomacy as well as economic development.

As a candidate for her party's nomination, Clinton advocates bold actions to reverse global warming and substantial investment in infrastructure, with "energy efficiency and sustainability" and job creation as prominent goals. She does not explicitly tether those goals to historic preservation, however, despite abundant proof that buildings are the primary source of energy loss and that the most efficient building is one that is already built.

Donald Trump

As with all things, Donald Trump's record on historic preservation is extravagant and not easily characterized. Much of his pre-reality television show fame was tied to his real estate deals, and the public imagination of old neighborhoods falling before Mr. Trump's gilded bulldozers may obscure the fact that Mr. Trump has some track record of bringing new life to historic structures through modern uses.

The most over-the-top example of Mr. Trump's historic preservation sensibilities may be his restoration of his Palm Beach, Florida residence and private club, Mar-a-Lago. This 1927 palatial estate of cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post was bequeathed to the federal government for its potential use as a "winter White House." When the government deferred, the estate sat empty for more than a decade until Mr. Trump bought it, furnished, for a mere $10 million in 1985. He then spent years restoring the property with his then-wife Ivana.

According to the Palm Beach Post:

Originally, the main house was 55,700 square feet, with 118 rooms, 58 bedrooms and 33 bathrooms. [A designer] frosted Mar-a-Lago in an unrestrained river of gold leaf, gold bathroom fixtures, rare marbles, carved stone and ancient Portuguese tile. Rooms were modeled after European palaces. Workers used up the country's entire stock of gold leaf when gilding the living room, with its 42-foot ceiling.

As the rescuer of Mar-a-Lago, Trump invested millions of dollars and many years on a historically sensitive rehabilitation of what the club's website claims is "the greatest mansion ever built." He also donated easements on the property to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, ensuring preservation of the property in perpetuity while affording Mr. Trump tax benefits.

Mere feet down Pennsylvania Avenue from the home he hopes to occupy, Mr. Trump recently embarked on redevelopment of the Old Post Office Pavilion, one of DC's top ten most visited landmarks, into a luxury hotel. His project bid promised to respect the building's historic character. Senator James Lankford (R-OK) chafed at Mr. Trump's use of federal historic tax credits to make the project economically viable, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation defended their use.

The impacts on cultural heritage resources of Mr. Trump's proposed 3,000 mile wall on the nation's southwest border was a target of pointed humor by comedian John Oliver. Oliver's sendup included a clip of testimony from the Chairman of the Tohomo O'Odham Nation about the unrestricted desecration of native graves when the feds built an earlier southern border fence. Fragments of human remains showed up in the treads of construction machinery.

Bernie Sanders

Before he found success in politics, Senator Bernie Sanders had a brief career in Vermont historical interpretation. During 1979 and 1980 he created and sold filmstrips to Vermont schools and libraries. In a brochure for the American People's Historical Society, director Bernard Sanders explained, "It is our belief that state and regional history has too long been neglected by the audio-visual industry, and we are happy to begin the process of rectifying that situation. We believe that students have the right to learn about the state and region in which they are living."

Senator Sanders carried his interest in historic preservation topics into his four terms as Mayor of Burlington, Vermont. Under Mayor Sanders, the city became the first in the nation to adopt the Community Land Trust as a means of helping to ensure that middle and lower income residents maintain some control over and access to housing and public spaces. To this day the Burlington Management Plan speaks to the ability to restore and maintain historic structures while maintaining their affordability:

Burlington's rich and varied historic and architectural legacy, the result of more than two centuries of development, remains a vital link to the city's history, and plays an active part in its future.

Then Representative Sanders came to the rescue of the preservation community in 1995, when the House Appropriations Committee proposed to eliminate the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. Rep. Sanders offered an amendment to restore the Council's funding, which was approved by a convincing vote of 267 to 130.

As a candidate for the Democratic Party nomination, Senator Sanders, like Secretary Clinton, calls for bold measures to advance energy efficiency and sustainability without specifying historic preservation's critical role. He also recently called for greater social and economic justice for Native Americans, stressing the importance of native sacred spaces and of including native voices in decisions over these lands.

Ted Cruz

There is not much specific to the issue on the public record from which to discern Senator Cruz's feeling toward government's role in cultural heritage protection. His areas of policy concern throughout his career have focused on law enforcement and social issues. There are two major areas in which his philosophy is likely to impact historic preservation, however, and neither of them in a good way.

First, Senator Cruz opposes the extent of federal land ownership, specifically in western states like Nevada. The issue recently came to the fore during the Bundy militia's occupation of Oregon's Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. In a February campaign spot, the Cruz campaign advocated returning several national monuments to control by states or private citizens. This position is significant because the federal government holds itself to a much higher standard of stewardship of cultural resources than do the states - due in large part to the provisions of the NHPA. Many states have weak or nonexistent protections for historic buildings, traditional cultural properties, and archaeological sites.

Second, Senator Cruz is proposing to rewrite the tax code, and in the process purge the job generating historic rehabilitation tax credit. Perhaps Senator Cruz has an alternate strategy to redevelop anchor properties during a tough market, but he does not appear to have made it public.

The Road Ahead

The first Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places, William Murtagh, remarked, "It has been said that, at its best, preservation engages the past in a conversation with the present over a mutual concern for the future." One might say the same thing about presidential campaigns, at their best.

As part of Preservation50, the Advisory Council for Historic Preservation and partners are inviting public input on how to ensure an even brighter future for cultural heritage protection and its public use in the next fifty years. One way of doing so is to elect presidents, senators, and congresspersons who seek not only to make history, but to save it and learn from it.

Greg Werkheiser is a founding partner of the law and policy firm Cultural Heritage Partners, PLLC, which is managing the Preservation50 initiative. Co-authored by Marion Forsyth Werkheiser and Ellen Chapman, also of Cultural Heritage Partners.