What's it like to live in Louisville, Kentucky with one of the shortest lifespans in the U.S.? This fact may be unknown to most but it is frightening those whose lives are needlessly cut short. Longevity and the number of years of healthy life here in the state of Kentucky, the city of Louisville, and particularly neighborhoods like West Louisville are among the shortest in the nation. Strongly associated with this these shortened lives is that these places have some of the worst air pollution in the country.

Across America, indeed, states with cleaner air have citizens who live longer. The Centers for Disease Control show that in real numbers: the 53,000 Kentuckians who are 65 and over are sicker than the national average. The healthiest Seniors in the U.S. are in the similar size state of Oregon where its 94,000 elders are healthier than Kentucky seniors. For the nation as a whole 73% of citizens self-report that they are "healthy" at age 65, but that number decreases to, 62% in highly polluted Kentucky. Sixty-five-year-olds in Oregon, a state with strong environmental regulations including clean air protections, rate themselves the healthiest at 78%. Senior blacks in Kentucky (56%) are even less healthy.

Louisville is also ranked as having one of the shortest lifespans for poor men in the nation. The Journal of the American Medical Association reports that the lives of poor men in Louisville are about 1,643 days or four and half years shorter than those in Santa Barbara which has some of the cleanest air, water and soil in the nation. In Louisville, for example, differences in life expectancy can be as much as 13 years from one West Louisville neighborhood compared to East Louisville according to a report "Building a Healthier Louisville" by the Greater Louisville Project. Our analysis using the same data finds a ten-year difference between East and West neighborhoods.

Our city leaders, foundations, and industry have betrayed us with junk science that is a cover up for the causes of these shortened lives. Why didn't the prominent foundations of Louisville, which spent hundreds of thousands of dollars, hire a team from the School of Public Health and Center for Sustainable Urban Neighborhoods at the University of Louisville? Instead they chose to produce an unscientific study to cover up how industrial pollution is shortening lives. The leader of the Greater Louisville Project, which has strong ties to the Mayor's Office and Chamber of Commerce, has no medical degree or Ph.D., just a Master's degree in business from a local college. The Greater Louisville Project broke another scientific rule by refusing to share their data with University of Louisville investigators. Echoing activities from the infamous Watergate debacle, the data were leaked to us for further study.

Louisville provides a powerful case study of the uses and misuses of statistical analysis in arguments about how "place" shapes lives. According to Greater Louisville Project analyses, low levels of individual educational attainment appear to be the single best predictor of premature death, an even stronger determinant than income or exposure to environmental contaminants. The problem is that the Louisville study overlooked a basic fact all first-year statistics students learn: correlation is not causation.

When the study was released, the media touted the idea that lack of education is the primary explanation for neighborhood gaps in premature death rates. The Louisville Courier Journal made it front page news and even produced a short video stating the solution to a longer life was riding in a "yellow school bus." But consider the odd logic: Do health officials really mean that high school or college degrees are the prescribed remedy for cancer, lung and heart disease? Common sense - and sound science - reveal that two people breathing the same amount of toxic air are going to be similarly affected, even if one is a high-school dropout and the other has earned a PhD degree. People with advanced degrees are not immune from toxic fumes in the water, soil, and air. The point they might be making is that higher education enables people to live in cleaner areas or they might make smarter decisions of where to live away from pollution. But moving all residents from West Louisville is hardly a policy option.

Another major problem is the report's emphasis on lack of access to medical care as a major contributor to premature deaths. In fact, residents of Louisville neighborhoods with high premature death rates live about half as far away from the city's major medical center as other residents typically do. This statistical fallacy is like claiming that hospitals are bad for you since so many people die there.

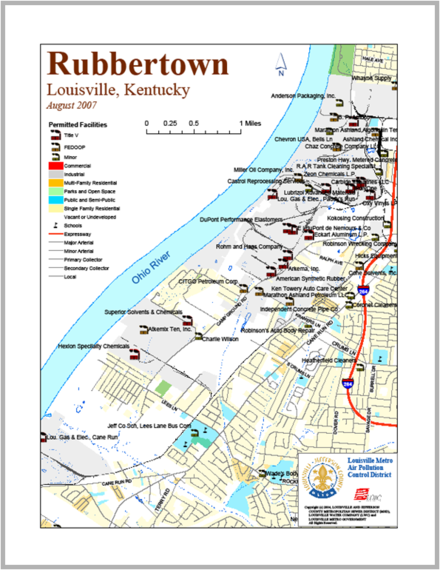

The Louisville study claims that environmental factors have a minimal effect on premature death rates giving it a measly weight of just 10%. Our research suggests they are a far more powerful factor. We examined Louisville neighborhoods, using two different measures of environmental degradation. One refers to the location of "brownfield sites" in which dangerous toxins were abandoned on formerly industrial sites primarily in poor and black neighborhoods of West Louisville; and the second refers to proximity to chemical factories in a neighborhood known as "Rubbertown."

Using standard statistical techniques, we found that such environmental contaminates constitute a major cause of shortened lives in Louisville. Once the high concentration of brownfields and toxic stew of chemical companies are taken into account we found, as we reported at the 2014/2016 Annual Conference of the Urban Affairs Association, in a policy brief published by Harvard's Scholars Strategy Network and an article in the scholarly Journal of Urbanism, that environmental pollutants equal the impact of racial and income disadvantage. But it is race and income that shapes where we live in hyper-segregated Louisville with blacks and the poor not being able to escape from these pollutants.

Beyond bats, bourbon, and horses, Louisville has the well-deserved reputation as the junk science capital of the world starting with the fraudulent smoking studies in the 1960's. Louisville already has enough blood on its hands with these erroneous studies. Now we have a new set of studies repeating these methodological and statistical errors that ignore the hard science on the subject.

But we don't have a pollution problem just here in Louisville or in Flint, but in hundreds of cities where air, water, and soil pollution sit next door to mostly poor and minority neighborhoods. There is another word for this: environmental racism.

Frustratingly, saving lives and cleaning the air require bucking politics where elections are routinely won by politicians who decry environmental protections as "job killers." But the real "killer" is pollution. Effective environmental protection, not junk science, can reduce the disparity between healthy living in Louisville and most of the rest of the nation.

John I. Gilderbloom recently accepted a position as Professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Louisville while he still Directs the Center for Sustainable Urban Neighborhoods. http://sun.louisville.edu.

Gregory D. Squires is a Professor of Sociology and Public Policy & Public Administration at George Washington University. https://sociology.columbian.gwu.edu/gregory-d-squires