The answer in the New Year to the inflation conundrum may be at hand, the conundrum that has kept the Fed pushing down interest rates since the Great Recession and recovery. Why aren't prices rising faster with all the QE stimulus programs that have injected literally $billions into the economy?

The answer maybe that it has taken 8 years for Americans' median incomes to have recovered the ground lost since the beginning of the Great Recession--8 years. There is no other plausible explanation for why consumers haven't spent enough to push up prices during the now six year recovery. They are still in a deflationary mentality, brought on by the worst downturn since the Great Depression--which lasted some 10 years, let us not forget.

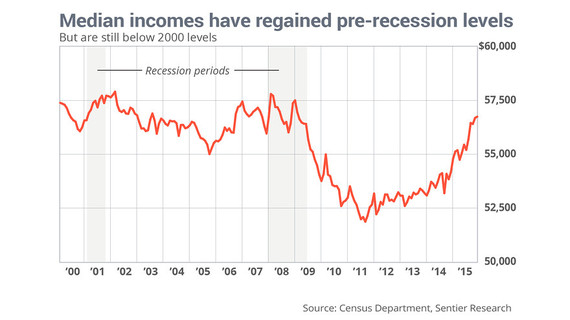

A report released Tuesday by Sentier Research drew on Census Department data shows what a long, hard climb out of this recession it's been. And we know what depressed incomes--and job prospects--will do to so-called animal spirits--the term coined by JM Keynes to describe deflationary times as happened during the Great Depression.

The medium income is just 1.9 percent higher than where it was in June 2009, the beginning of the economic expansion. Perhaps even more discouraging, the median income is 1.1 percent lower than in January 2000, when record-keeping began. Average weekly earnings adjusted for inflation are just 5 percent higher in November 2015 than they were when the recession began, whereas the inflation rate has risen more than 10 percent over that time.

And, such a small increase may be a reason consumers are saving more than they are spending these days. There is almost no inflation with oil and commodity prices in general falling these days. And research shows that consumers tend to spend more when prices rise over the longer term, and conversely wait longer to buy when prices are level or even discounted. This may fly in the face of so-called conventional wisdom. Otherwise, why all the discounts and specials offered these days?

The Fed has been most concerned with little or no inflation, rather than higher inflation, because it means less demand for products and services. And demand is a two-edged sword. Consumers may have the means to buy, but not the will when they see prices falling, as they are for many goods and services today.

In other words, if prices go down, conventional wisdom says the situation would likely encourage more buying (Remember Say's Law, anyone?). But it can actually have the opposite effect. If consumers and corporations expect prices to continue to go down, they will often delay purchases, waiting for a better price--dramatically slowing demand and causing prices to drop further. It leads to a downward spiral that reduces the circulation of money through the economy, which may limit growth--which is the situation today.

This is well-known to economists such as Paul Krugman and former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke who studied the Japanese 1990's period of prolonged deflation, and its belated attempt to boost prices. Recent noteworthy efforts to curtail deflation include Japan's current monetary stimulus program, the European Central Bank's recent lowering of its interest rate and quantitative easing (QE) programs in the United States.

In the 20th century, there were two main examples of deflation's effect on economies: The Great Depression of the 1930s, which began in the United States and spread globally, and Japan's "lost decades," which began in the early 1990s

So the median annual household income was $56,746 in November. That's barely above October's median of $56,688, but it was enough to top the $56,688 reached in December 2007, when the recession began.

Does this mean consumers (and the businesses that serve them) might finally be ready to spend enough to boost the inflation rate high enough to grow the economy again, and shake off the deflationary mentality? We need at least 3 percent GDP growth to pay all the bills, and reduce the federal budget deficit to a manageable level.

The Conference Board's Consumer confidence index rebounded in December to a reading of 96.5, up from 92.6 in November. The present situation index increased from 110.9 last month to 115.3 in December, while the expectations index improved to 83.9 from 80.4 in November. And the U. of Michigan Sentiment Survey is up 8/10s from the December flash to a higher-than-expected final December reading of 92.6. It may just be higher holiday spirits, of course.

We know from the Great Depression just how long it took for animal spirits to rise, and shake off those deflationary expectations that keep consumers saving more than they are spending. So the return of median incomes to pre-recession levels should be good news for next year growth, since consumers power approximately 70 percent of GDP growth. If only our business interests would understand this, and why consumers hold back, even when they are feeling better! Corporations might then begin to invest more of their record profits in productive enterprises that would create those oh so necessary jobs.