Bees are still dying and EPA is still sitting on its hands. Luckily for those of us who like to eat, scientists have been hard at work cracking the "mystery" of colony collapse disorder (CCD). Today two new studies were published in Science, strengthening the case that neonicotinoid pesticides are indeed key drivers behind recent pollinator declines.

To avoid in advance some of the inevitable confusion on this topic, nobody is saying that neonicotinoids are the culprit behind CCD. Most scientists now believe that we have been losing more than a third of our hives each year since 2006 from a combination of factors acting in concert: pathogens, pesticides and nutritional stress. The debate has lately been over which is the more critical catalyst, and in the last year pesticides have rapidly risen to the top.

Regulators in the U.S. remain paralyzed by this debate, despite ongoing public demand for decisive action.

Today's studies come on the heels of a year of damning evidence for these pesticides: three separate studies in the last year confirmed that low-level exposures to neonicotinoids synergize with a common pathogen to dramatically increase bees' susceptibility to infection and the likelihood of death. In one long-awaited study published in January, exposure levels were so low as to be undetectable. And Italian researchers have proven, yet again, that in a single flight over freshly-sown corn fields, bees can be exposed to neonicotinoid-contaminated dust from planters depositing treated seeds at acutely toxic levels. This means they die right away. These same researchers have shown in 2010 and 2011 that sub-lethal exposures impair bees' learning and memory.

Today's two new studies show similarly indirect effects that are nevertheless lethal. One uses a new method (gluing little radio frequency devices to bees, then tracking them in a field environment) to confirm what previous studies have shown: sub-lethal neonicotinoid exposure disrupts honeybees' foraging and homing abilities. The other shows that environmentally relevant neonicotinoid exposure reduces queen fitness in bumblebees, causing an 85% reduction in the number of queens produced. Bumblebees don't really get CCD because their lifecycles and hive structures are different from honeybees, but they and other wild insect pollinators have likewise seen their populations drop off a cliff in recent years.

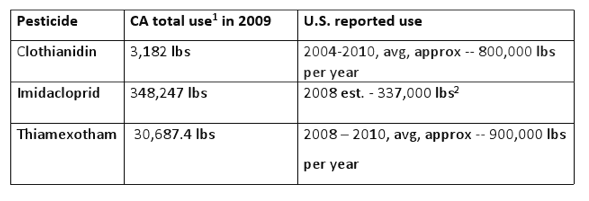

Wild pollinators and honeybees alike have been facing an increasingly toxic landscape since the introduction and rapid uptake of neonicotinoids in the late 1990s. Mining data from USDA, EPA, industry and California's pesticide use reporting system (the only one of it's kind), here's a snapshot of what bees are facing in the field:

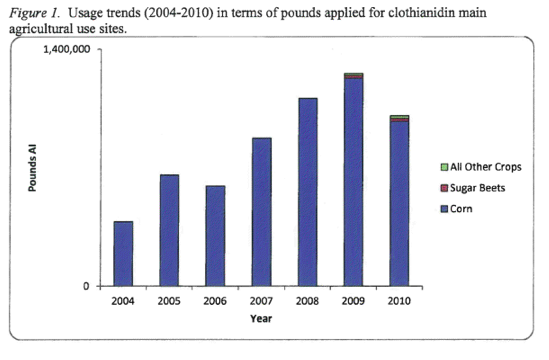

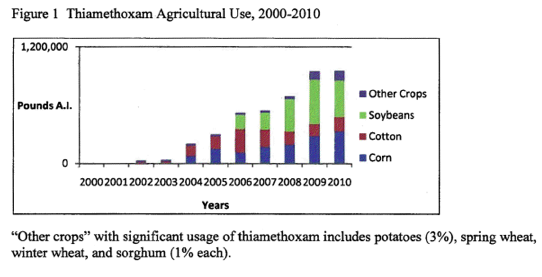

- Over 2 million pounds of clothianidin, imidacloprid and thiamexotham (three neonicotinoids) are used in an average year. And given use trends (see tables below) this figure is likely quite low.

- At least 143 million of our 442 million acres of cropland is planted with crops treated with one of three neonicotinoids: clothianidin, imidacloprid and/or thiamexotham. This is a low estimate that does not begin to account for non-agricultural uses.

- 83+ million of these acres are corn, upon which honeybees rely for core nutrition (corn is wind pollinated, it doesn't need bees for pollination, but its sheer abundance of pollen makes it a staple source of bee forage).

In addition to being prevalent, neonicotinoids are long-lasting, systemic pesticides. So any problems caused by their widespread use are compounded by the fact that they are accumulating, year on year, in the soil. They are also present in every part of a treated plant because, being "systemic," they are often taken up at the root and expressed throughout the vascular system of a plant in pollen, nectar and guttation droplets (think plant sweat).

So, to recap: these pesticides are prevalent, persistent, and more scientists confirm everyday that they are making bees sick (or dead) through a number of different mechanisms and routes of exposure.

The sad truth? Beekeepers have been sounding this alarm from the ground for years. Would that we had listened.

This figure includes reported and unreported use (i.e. sales) from California's Department of Pesticide Regulation's Pesticide Use Reporting database. Imidacloprid & clothianidin data compiled by Dr. Susan Kegley, consulting scientist at PANNA.

Based on EPA's 2008 Screening Level Use Analysis. Note: This figure is a low estimate. Pesticide usage data obtained from various sources. The data are then merged, averaged, and rounded. Agricultural use sites (crops) that the pesticide is reported to be used on. Available pesticide usage information from U.S. states that produce 80% or more of a crop, in most cases, or less than 80%, in rare cases, depending on the scope of the survey and available resources. Annual percent of crop treated (average & maximum) for each agricultural crop. Average annual pounds of the pesticide applied for each agricultural crop (i.e., for the states surveyed, not for the entire United States).

Charts by EPA