Walking through the Louvre, I was struck by a group of grade-school children sitting on the floor being instructed in front of Éugene Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People (1830).

They were learning about French history and the time-honored tradition in France of revolution, utilizing the painting and all of its genius visual metaphors. I began to wonder if successful political art was a 19th-century phenomenon.

In the well-crafted essay for his exhibition currently on view at MoMA PS1 and simply titled "September 11," curator Peter Eleey discusses a figurative work (Tumbling Woman, 2001) that Eric Fischl made following, and in commemoration of, the tragic events of that day.

When placed on view in Rockefeller center in 2002, public response to the sculpture was so volatile and filled with disgust and horror at the realistically rendered image of a woman suffering, that the work was not only immediately removed, but all references to its existence also seemed to vanish.

Fast forward ten years and Fischl is engaged in a project titled "America: Now and Here," which posits that America could benefit from the insight of artists as a means by which to, if not cure, then, positively nurse toward health our ailing country. Fischl's initial concept was to ask a fairly vast number of his artist friends to create work about what America means to them -- now and here -- and then travel the works around the country in railroad boxcars to stop in places where contemporary art is neither a mainstay nor a fixture.

Now this outline is being applied in other communities, including the Roaring Fork Valley (which includes Aspen) in Colorado. Ask Jasper Johns what America means to him now and here as Fischl did and you get what you might expect -- a gorgeous drawing with a monochromatic orange background with an American flag floating in the top third of the image (a work simultaneously evoking the infamous post-9/11 system of color-coded threat levels and his own 1957 painting Flag on Orange Field). But ask an artist that you have never met and have no idea of their medium, let alone their conceptual framework or their politics, and the risks run significantly higher. As Carol Hanisch said, "The personal is political."

What is the role of the curator in addressing politically charged or other relevant topics? Two extremely different curatorial approaches are on view now.

Current Istanbul Biennial co-curators Jens Hoffman and Adriano Pedrosa have taken deceased artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres "as a muse" and concentrated on themes that are arguably the primary concerns of the late artist: "sex, death, love, and politics." But, Gonzalez-Torres's inability to discuss his willingness to have his signature titling convention -- "Untitled ( )" -- utilized for an exhibition in which his work is not included for all intents and purposes "allows" the curators to impose a rubric under which artworks are grouped together according to such criteria as the sexual orientation of their creators or their superficial subject-matter -- for example those that feature representations of guns.

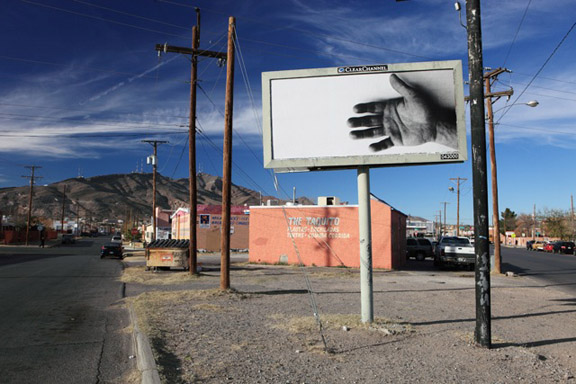

"Untitled" (For Jeff), 1992, Photo: Mary Snortum Studio, Installation in El Paso, Texas for Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Billboards at ArtPace, San Anotnio, Texas 2010 © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

"Untitled" (Ischia), 1993, Photo: Peter Muscato © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

"Untitled" (Death by Gun), 1990, Photo: Herling/Vogt, Installation of Felix Gonzalez-Torres at the Sprengel Museum Hanover, Germany, 1997 © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

"Untitled" (Lover Boys), 1991, Photo: Axel Schneider, Installation of Specific Objects without Specific Form at the Museum fur Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, 2011 © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation

It is a curatorial decision that might well minimize the artist's intentions. In direct contrast is Eleey's curatorial approach within the previously mentioned "September 11" exhibition. Here too, the curator has taken a risk by grouping together works within a context that did not even exist when the majority of the works in the exhibition were created (more than two-thirds of the works in the show date from before the 2001 attacks).

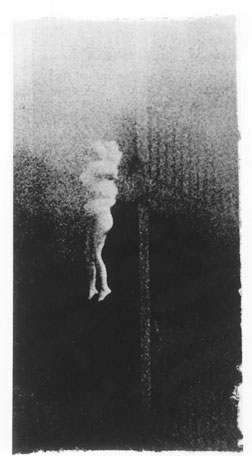

Importantly, however, Eleey spoke to the exhibiting artists to discuss how the events of September 11 have altered the way a viewer can look at and consider their works -- for example, Sarah Charlesworth's 1980 black-and-white print of a figure suspended in space (Unidentified Woman, Hotel Corona de Aragon, Madrid) -- now, and to address how a previous reading of the piece may no longer even be possible.

Unidentified Woman, Hotel Corona de Aragon, Madrid. 1980. Black-and-white mural print. 78 x 42 inches (198.1 x 106.7 cm). Collection Ara Arslanian, New York. © 2011 Sarah Charlesworth; courtesy Sarah Charlesworth and Susan Inglett Gallery, New York

In analyzing each of these curatorial positions, one realizes that where the first prioritizes the authorship of the curator, the second centers on the power of the object. While both are subjective and, in the end, informative takes on the selected works, they offer the viewer highly antithetical approaches to their individual subject matter.

On September 11 this year, I stood, and then later sat, on the floor of a MoMA PS1 gallery experiencing Janet Cardiff's The Forty Part Motet (2001) over and over again. Like many others, I recalled having heard Cardiff's provocatively enchanting work in the same space in September ten years earlier.

My memory was alternately accurate and inaccurate, highly personal and oddly political, as I was subsequently told that Cardiff's 2001 exhibition did not actually open until October 2001.

Neither does it matter, though, as the artworks that will be sat in front of and utilized to discuss essential human values in the future will be those that continue to offer us unspeakable insight into matters that we as a society continue to feel compelled to reckon.