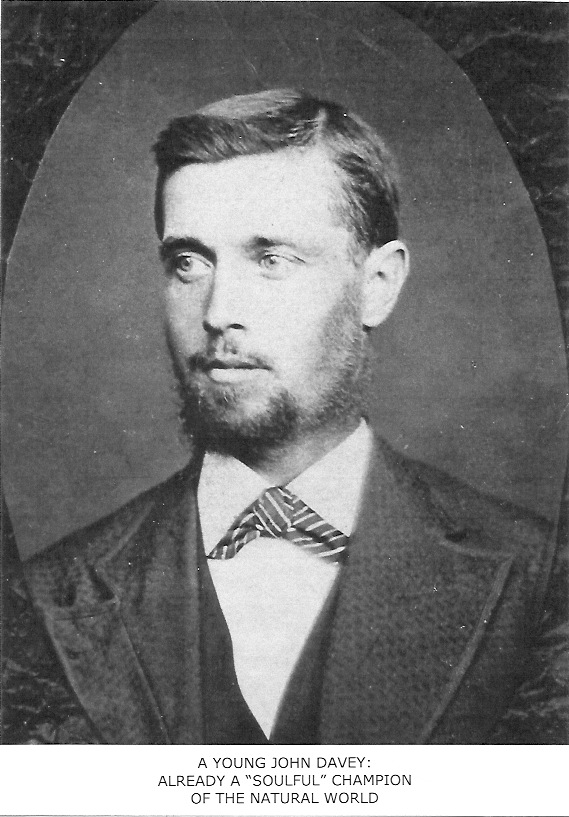

In this third part of my story about my grandfather, John Davey, the Father of Tree Surgery, I hope to continue to lay the groundwork for how I, as a psychoanalyst, view the development of his personality and character. I feel that the most important trait that my grandfather shares with other great people is that he was totally and completely incapable of being indifferent.

Let me explain what I mean by this.

In Kay Jamison's excellent book, Exuberance: The Passion For Life (2004), she writes about such people as Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir, though she might just as well have been describing my grandfather. She quotes Louis Pasteur:

"The Greeks understood the mysterious power of the hidden side of things," wrote Louis Pasteur. "They bequeathed to us one of the most beautiful words in our language - the word 'enthusiasm' - en theos - a god within. The grandeur of human actions is measured by the inspiration from which they spring. Happy is he who bears a god within, and who obeys it."

As Jamison points out, a defining quality of great teachers, statesmen, and adventurers is their ability to create infectious enthusiasm:

Those who are exuberant engage, observe, and respond to the world very differently than those who are not and, what is crucial, they have an intrinsic desire to continue engaging it. This is generally not a muted one; rather, it is one filled with a sense of passion, if not actual urgency.

My grandfather saw and felt nature with the passion of a lover and the patience of a scientist. Many people thought he was crazy. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

In Parts I and II, I described John's developing passion for nature, which I interpreted grew out of his experience of traumatic loss. From the loss of his mother, to his being "put out to service," John undoubtedly felt both bereft and constrained. Now, as I pick up the story of the spring of 1866, at the age of 20 my grandfather became a free man! No longer bound to position or place, or obligated to give his wages to his father, he could now shape his own destiny. He calls this his "second milestone."

And John knew exactly what he wanted to do with his freedom. Though never having traveled before, he headed south to Torquay (now known as "the English Riviera"), the seat of famous gardens and greenhouses. Here John could learn greenhouse management, horticulture, floriculture, and landscaping in the very thorough Old-World way. A friend of John's arranged for his position as "under gardener," and even found a place for him to board. There he apprenticed himself for the next seven years to a local horticulturist, learning everything he could about the plants and trees that so enchanted him.

But even more importantly, my grandfather had his first opportunity to learn to read and write. A kindly man took John under his wing, and taught him the alphabet. With only a copy of the New Testament and a dictionary, he laboriously learned to pick out words. After he acquired a grammar book, John painstakingly figured out how to craft words into sentences, and then sentences into paragraphs. And then, wonder of wonders, he was able to add a hymnal to his prized library of four books. I doubt if any four books ever contributed more to the destiny of a man. They stimulated and comforted him, making him feel like the richest person in the world. He knew there was going to be no stopping him now!

By the way, we still have that old, faded copy of the New Testament in the family. On it is a brown spot where a drop of milk had fallen long ago, as he studied with the little book on his knee while milking cows. He spent ten to twelve hours a day at hard physical labor, after which he then studied long into the night. This ability to work hard was noticed by everyone who knew him. At the end of his seven years apprenticeship, not only had John learned his craft, but he had acquired a sound basic education.

Throughout his life, my grandfather's passion for language and the exact meaning of words was legendary, and he later studied Greek and Latin. Greatly valuing his ability to read and write, he felt that words were indispensable to thinking: "Without words one cannot think, and it is thought that moves the world."

While in Torquay, John also further developed his spirituality. Through his landlady, he was introduced to a large circle of bright young men belonging to the Baptist Church. He writes, "It was not that my dear old Mother's (Episcopal) church was not appreciated, for I love her still, but in the Baptist Organization...I discovered the true spirit of God." He and his friends would travel around Torquay seeking converts by preaching, and it was during this time that John began developing his skills as an orator.

If you research John Davey on Google, you will find that he is referred to as a "spellbinding orator," but he was also a spellbinding writer, teacher, and person. He was a profoundly emotional man - soulful - and, as I stated before, he was totally and completely incapable of being indifferent. His love of people and nature was equally strong, and this sets him apart from many of our great geniuses - the majority of whom were loners.

Despite his allegiance to his church, my grandfather always maintained a strong sense of his individualized beliefs. He developed supreme confidence in himself and his abilities during these years in Torquay. The Rector of his church offered many times to ensure John's employment with a bank or other commercial establishment, thus securing his financial future. Still others in the church offered to pay his tuition and expenses for four years at Spurgeon College, the best seminary of the time. And his employer was begging John to stay on with the promise of more money, because he had never had such a good worker.

But John had other ideas.

To the kind people who offered to send him to the Seminary, he pointed out:

"The Calvinistic tenets imposed by the college are not those I can ascribe to. I have a better opinion of the Heavenly Father than to believe that a certain few should be saved and that all the rest should be eternally damned equally for His glory."

And about the commercial opportunities, he said," I never had a head for figures and besides I had decided to work with soil all my life." The thought of business just for financial gain made no sense to him, and left him cold.

However, for my grandfather to say he never had a head for figures is a massive understatement. Money simply never, ever was the motivating force that drove him forward. It was creative ideas and the desire to understand the mysteries of nature that stimulated him. Though his life was full of struggle, and almost indescribable hard work and deprivation, he was resolute in his determination to dedicate his life to the preservation of the natural world. It was his passion, his obsession, and his destiny.

So, not surprisingly, my grandfather began to hear the call of the New World. It was the great adventure of the Nineteenth Century, and John wanted to be part of it. With characteristic optimism and enthusiasm, in the spring of 1873, with no money and no real plan, 27 year-old John Davey set sail for America.

To be continued in Part IV....