I've failed many times. I failed recently and it feels awful. How about you? When was the last time you failed?

When we're very young we fail a lot. Look at any toddler as they learn to walk. It's pretty well understood that it's through failure and persistence that we learn to do things.

Fast forward a few years, and it becomes increasingly difficult for us to accept failure. We assume that we can't learn and grow at the rate that we could when we were kids. But is that really true? Maybe we stop growing because we're scared of failure.

The core of this essay came out of teaching Search Inside Yourself in France this summer where participants found some of the analogies below very useful.

Measuring Failure

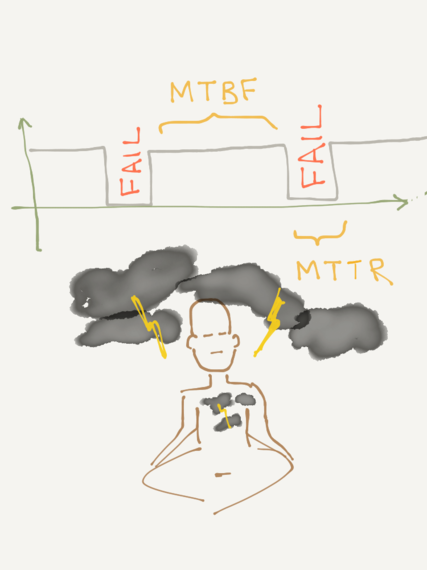

There are several different metrics we can use when measuring system failures. I want to use two of them to contrast ways of thinking about failure. The first is Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) and the second is Mean Time To Recovery (MTTR).

If you focus on increasing Mean Time Between Failures (or MTBF, the average time between failures), you tend towards building a highly controlled system that stays within safe bounds of operation. You harden your components, control your operating conditions, and are relentless in your pursuit of order.

When I worked at amazon in the early 2000s, both amazon and google were pioneering a slightly different way of thinking about the reliability of computer systems. They began to experiment with the idea of using very cheap components that were known to fail; so "failures" became routine occurrences rather than out-of-the-ordinary events. Then you bind them together with software that expects those failures, and works around them as quickly as possible. You start to focus, then, on the Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR) from a failure -- or the time it takes for the system to come back to being operational after a given failure.

The System of You

Think about what those two approaches mean for the System of You.

If you're reading this, you're probably old enough that you know that failure usually feels like poop. No one likes that feeling. Think of a time when you felt shame, when you let someone down, when you publicly made a mistake. It was probably uncomfortable and you may have resolved never to feel that again.

In other words, we start optimizing for a very long Mean Time Between Failures; possibly by doubling-down on our strengths, avoiding things that are unfamiliar, unknown, or uncomfortable,.

What would it look like to optimize for Mean Time To Recovery? To push the boundaries of the uncomfortable, to embrace failures, to fail fast and fail often (as the startup mantra goes), and to continue to get better at recovering quickly from those failures.

It may sound good in theory, but given how terrible failure feels, how do you actually do this?

Be with what IS.

At the most basic level, we need to learn to be with whatever is.

What will happen hasn't yet happened, so cannot actually harm us in this instant.

What was, by definition, has already manifested, and so cannot be changed.

Even what is happening in this instant is already in the process of unfolding, so cannot be changed.

But we do have a choice as to how we react to what is happening right now.

While it might be possible to accept all that intellectually, it still doesn't change the fact that failure feels awful in the moment. How do we learn to experience the very physical unpleasantness that comes with difficult emotions (like failure)?

This is exactly what we practice when we sit.

After we first train our attention, we learn to bring our attention to physical sensations in all different parts of our body, and observe their characteristics objectively, without labeling them as pleasant or unpleasant. We practice being with unpleasant sensations without pushing them away but instead just really noticing them like a scientist might observe bacteria under a microscope.

Very soon we realize that we need to be skillful not just with the unpleasant, but with the pleasant sensations too.

How could that be important -- isn't it good to feel, well, good?

If we cannot experience pleasant sensations with the same objectivity that we cultivate in the presence of unpleasantness, we quickly go from enjoying them to becoming attached to them. And then the moment they disappear (which they must), we crave them, and we are uncomfortable until we can bring them back.

In a way this is related to Carol Dweck's research on fixed vs. growth mindset, and the importance of praising effort vs. outcome. Praise feels good, and if the praise is for a positive outcome ("good job acing that test!") then we tend to only work on things where we expect to get a positive outcome. If the praise is for effort ("you studied hard for that test!"), then we are more open to working on things where our efforts will be recognized, regardless of the outcome.

In a way what we're talking about here is going one level deeper and weaning ourselves from the need to be praised or recognized -- regardless of whether it's for effort or outcome.

Sensations and MTTR

Wait a sec. Our goal was to reduce Mean Time to Recovery. Let's suppose you somehow master the art of "being with what is." How and why does that help reduce MTTR?

There are two aspects to this.

I often use the stubbed-toe example when I teach: take a moment to think about, and briefly re-live, a time you stubbed your toe; and the pain you felt...

Did you later say to yourself: "let me kick the table again so I can really remember what that stubbed toe felt like?" I doubt it.

And yet we do that all the time with our emotions. Something happens that causes us grief, and we re-play that incident over and over again in our minds. Each time we re-play it, we feel the grief, and try to push away that unpleasant feeling. And as we try to push it away, we analyze, dissect, and re-play it yet again.

As we get better with objectively observing sensations, the first thing that happens is that it becomes easier to experience the unpleasantness of failure as a passing bodily sensation, just like a stubbed toe. You can notice its onset, experience it in all its unpleasant and gory detail without needing to push it away, and notice as it passes (as everything does). There's no need to continue to relive it. We can see ourselves as a sky with dark clouds currently passing through us, rather than identifying with the darkness.

As we learn to experience our sensations objectively, in finer levels of detail, and without pushing away the unpleasant or grasping for the pleasant -- the second thing that happens is that we develop an ability to also make better cognitive sense of them. For example:

How much of our grief is from some actual impending issue ("my rent is due and I'm broke")?

How much of our grief is from current events not reflecting a mental picture we've created to describe who we are (e.g., traits such kind, conscientious, hard working; and roles like engineer, husband, father)?

And how much of the grief is from worrying about the effect on meticulous PR job we've done our whole life, creating mental pictures in other people's minds ("what will so-and-so think of me when they hear about this?").

Once we can tease apart these factors, the magnitude of the grief we experience is often reduced significantly, and it becomes even easier to recover rather than stew in worry, anger, shame, or other negative emotions.

Why embrace failure?

Backing up a moment -- isn't it good that failure feels terrible? Isn't that what helps drives us to succeed, and navigate away from mistakes?

I'm in no way suggesting a masochistic love of failure.

I love how we talk about self-management in the Search Inside Yourself class as

a shift from compulsion to choice

"Unpleasantness" is an amazing set of data points that we are getting about a situation. Normally we are reacting to the unpleasantness by keeping it at arm's length, we are in effect compelled, trapped or victimized into a course of action by our desire to get rid of that unpleasantness.

I'm advocating learning to integrate these data points into a broader understanding of a situation and then proactively choosing the most skillful course of action.

But like any skill, this too is a skill that needs to be practiced.

Back to the cushion

So as we practice being with the pleasant and unpleasant on the cushion, we get better at recovering from life's setbacks.

As we get better at recovering from life's setbacks, we stop over-indexing on safety and are more open to taking risks and exploring opportunities.

When those pan out, great!

In case they don't, we get more practice at failing (and recovering), and feel even more liberated from the fear of the unknown.

So while you may think of meditators as sedentary and stationary; I believe there's a way in which sustained practice can support a life of great adventure and exploration!

Footnote

In a way I feel vulnerable writing this. You may have read memoirs where the authors celebrate and glorify their failures, while writing from a vantage point of success and subsequent accolades. Part of me is thinking: "What if that high point never comes for me? What if this is as good as it gets?"

However, among the things I'm grateful to have experienced and observed first-hand these past few years is that nobody is spared from the pains of being human. Not the the super-wealthy, not the successful entrepreneurs and executives, not movie stars, not the suits, the hardhats, and no -- not even the monks.

Which is why I'm pretty sure that you too have felt this uncertainty at some point in your life.

And so I wanted to share this post from "the trenches." From a place of peacefully walking through a plateau of not knowing what comes next.

This post originally appeared on the meditation minutes blog.