One hundred years ago, Canada and the United States signed the historic Migratory Bird Treaty to protect birds from indiscriminate slaughter for food and fashion markets. Millions of birds were killed each year and few species were spared, including unlikely ones such as robins, bobolinks, and meadowlarks, as well as egrets, herons, shorebirds, ducks, and grouse. Bird populations dwindled, spurring one of the earliest conservation crises and a historic agreement between two countries.

Millions of birds like the Great blue heron were slaughtered annually for fashion markets. By 1910, populations had crashed and plumes were worth more than their weight in gold. Photo credit: ©Jukka Jantunen.

The Migratory Bird Treaty, signed on August 16th 1916, was implemented through Canadian and American federal legislation making it illegal to kill, import, export, sell, or purchase migratory birds, their nests, and eggs. Over the next century, it ushered in several critical reforms: abolition of hunting for food and fashion markets; bag and season limits on hunting game birds; new protections from pollution; and habitat protection through establishment of wildlife refuges, migratory bird sanctuaries, and stewardship initiatives.

Ratification of the Migratory Bird Treaty and subsequent conservation successes of the 20th century resulted from cooperation among hunters, naturalists, writers, scientists, industries, environmental organizations, governments, private citizens, and elected representatives.

The plumes, or aigrettes, of egrets and herons were especially prized for women's hats. Photo credit: ©W.M. Morrison.

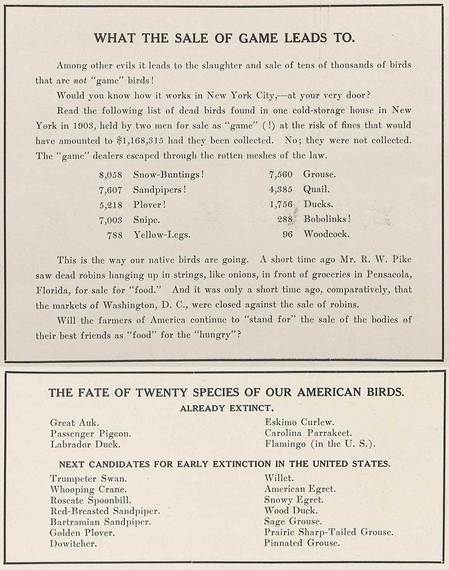

William T. Hornaday was one of the most ferocious and relentless advocates for the protection of wild birds and the Migratory Bird Treaty. As founding director of the Bronx Zoo, operated by the newly-formed New York Zoological Society (the precursor to my current organization, the Wildlife Conservation Society, or WCS), Hornaday was uncompromising in his position. He published dramatic accounts of the extinction of several species such as Great Auk, and the presumed plight of other birds like the Great Egret if the commercial market for wild birds persisted.

When efforts were flagging, Hornaday rallied support, pushing for the expansion of proposed protected species to include most migratory birds. And when the Treaty process had apparently stalled, Hornaday tracked down a missing Canadian document to a British embassy cabinet where it had been sitting, misfiled. The treaty was signed soon after and Hornaday called it 'the greatest victory ever achieved for the birds of this continent'.

Today, WCS continues to play an important role - discovering new ways to protect myriad avian species and their habitats, leveraging partnerships with others, and inspiring people to share in our mission.

Hornaday's vivid testimonials on the fate of North American birds were part of his relentless campaign for bird protection and the Migratory Bird Treaty. From The Wild Life Call, March 1911, Number 1. Edited by William T. Hornaday, Director New York Zoological Park, ©WCS.

The Migratory Bird Treaty was crafted to protect wild birds from intentional killing for commercial markets and to recover dwindling populations. What was not anticipated when the Treaty was written was the rise of new and different forms of human activity that would result in the unintentional harm or killing of birds in the late 20th and early 21st century.

More than one-third of the 1,154 native bird species of North America are in need of urgent conservation action. Each year, billions of birds are killed and nests are lost as a direct result of human activity, including collisions with vehicles, buildings, and power lines; predation by domestic and feral cats; and, as a result of agriculture, forestry, and fishing by-catch.

A regulatory framework governing incidental death of birds under Migratory Bird legislation, combined with enforcement of existing Migratory Bird Regulations, is critical and decades overdue. But birds face other threats: habitat loss and fragmentation, pesticides, and climate change, among others. Effective recovery of all birds requires commitments to collaborate across borders and across agencies. The geography of our shared birds transcend the government systems developed to protect and manage our environment.

Lapland Longspurs migrate in the thousands along roads on their way to Arctic breeding grounds. Unfortunately, this makes them especially vulnerable to mortality from vehicle collisions. These six were among many that collided with a large truck on the Klondike Highway of the Yukon. Photo credit: Hilary Cooke/WCS Canada.

The successful cross-border partnerships initiated 100 years ago should inspire us to work even harder to identify shared values and goals while leveraging collective knowledge and capacity. Such efforts will secure a future for all North American bird species while inspiring other international collaborations on migratory birds.

Our ultimate goals should be to ensure that no bird is added to Hornaday's list of extinct species. I do not wish to end my career with regret knowing that, despite our knowledge, capacity, and tools to secure the future of North America's birds, we failed to rise to the challenge. So let us seize the opportunity of this 100th anniversary of the Migratory Bird Treaty to catalyze a new era of collaborative conservation.