Loew's Kings Wonder Theatre, view from mezzanine level, 2010. Ruin porn?

In his recent essay "Detroitism," John Patrick Leary responds to two photographic collections, by Andrew Moore and by Marchand and Meffre, detailing the abandoned buildings of Detroit with a question: "What does 'ruin porn' tell us about the motor city?" By the end of his analysis, he has given us an answer - the photographs compel us to try to put together the story of Detroit and of an economically beleaguered America, but in the end they fail to do so, which "testifies... to the limitations of any still image."

Abandonment Photography and 'Ruin Porn'

As a photographer who studies modern ruins, I would like to collapse a fallacious generalization that Leary repeatedly makes in his analysis. Leary's obvious viewpoint on abandonment photography in general can perhaps be best summed up by his suggestion that "one often finds oneself asking of [modern ruins photography] first, 'What happened?' followed swiftly by, 'What's your point?'" Leary's fallacy is that he never addresses the fact that there are a variety of salient answers to the latter question.

Without any other information, I hand you an envelope and tell you that it contains a photograph of an unclothed woman. If I am an illustrator who works in the field of medical texts, you might assume that it is a reference photo I am using for a drawing. If I am Imogen Cunningam, you might assume that it contains a beautiful art print. If I am Larry Flynt, you might assume that it contains something that you should either burn or hide under your mattress.

Leary's primary mistake is to assume that all photographers who concentrate on modern ruins are Larry Flynts. Leary states that "even with the best intentions, ruin photography cannot help but exploit a city's misery"; he defines some elements of 'ruin porn' as "the exuberant connoisseurship of dereliction; the unembarrassed rejoicing at the 'excitement' of it all, hastily balanced by the liberal posturing of sympathy for a 'man-made Katrina.'" Leary makes clear that the 'ruin porn' usage is centered on exploitation, which raises a question - if an image is exploitative in nature, what does it exploit? Before examining where such exploitation might exist, I'd like to point to places where it clearly doesn't.

Intentionality, Context, and History: What Isn't 'Ruin Porn'?

Leary has assumed a tautology - a logical equivalence - between "abandonment photography" and "ruin porn." This tautology is not valid, and Leary dances around this notion without addressing it: "Indeed, what is most unsettling - but also most troubling - in Moore's photos is their resistance to any narrative content or explication." In bringing up this lack of context and applying it to all modern ruins photography, Leary neglects the entire class of ruins photography centered around documentation. Since the invention of the daguerreotype, photographers have been studying ruins; Rome and Egypt were very common destinations for lensmen. Modern ruins are no different, and indeed, are often studied with the same historical and documentary intentions as these early explorers.

The Garrick theatre. Photograph by Richard Nickel, Courtesy of the Richard Nickel Committee, Chicago, Illinois.

Probably the greatest ruins photographer of the 20th century, Richard Nickel was active in the Chicago area from the 50s through the early 70s. An avid historian and an immensely talented photographer, Nickel was enamored with the architecture of Louis Sullivan, and lamented the fact that it was being torn down at a rapid pace. During the years he was active, Nickel created thousands of medium format negatives, primarily of Sullivan commissions that were endangered or being demolished. His archive is by far the best extant record of these buildings. In effect, a ruins photographer is the primary reason we have a detailed document of an entire body of architecture.

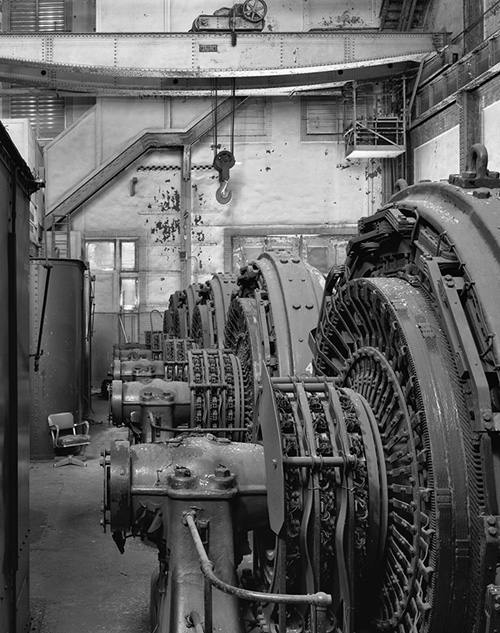

IRT substation #11, Manhattan. Photograph by Christopher Payne, courtesy of the artist.

Present-day ruins photographer Christopher Payne's New York's Forgotten Substations details the history and functioning of the now-decommissioned substations which used to power the New York City subway system. The large-format black-and-white photographs in this book are an amazing visual record of a now-outmoded class of structures. Importantly, it is the only such collection available.

Ruins photography can also serve as a small, but integral, sidenote to a complete history. Clifford W. Zink's compelling monograph The Hackensack Water Works contains a handful of contemporary photographs of the now-abandoned titular plant and its intact pumping engines. The majority of the book is devoted to a complete account of one of the most historically significant waterworks projects in America. The photographs serve as an elegiac indictment of a society willing to let a cultural treasure such as this fall into a state of disrepair.

In all of these cases, there is a clear intentionality on the part of the photographer to capture and document something that is likely ephemeral and certainly important. It seems almost absurd to attack work of this nature, and yet this is exactly what Leary does in his indictment of "liberal posturing of sympathy for a 'man-made Katrina.'" Nickel was a highly politicized figure, pushing like Sisyphus to preserve the structures he was documenting. Payne is entirely apolitical, presenting a documentary record without an agenda. The photographers who portrayed the waterworks after its abandonment likewise have no overt agenda, and yet in the context of a remarkable history, their work appears 'guilty' of what Leary accuses - it arouses our sympathies for an important cultural relic that has been woefully neglected. It seems absurd to accuse any of these photographers of either exploitation or 'rejoicing.' Clearly, Leary's tautology fails.

Sensationalism, Exploitation, and Artifice: What is 'Ruin Porn'?

Disproving Leary's erroneous conflation of abandonment photography with 'ruin porn' in the pejorative sense does not disprove the existence of the latter. Is there such a thing as 'ruin porn' - a class of images of derelict structures that is, by nature, exploitative? Surely there is, as I've created such images myself.

I feel that the victims of exploitation in this sort of abandonment photography are not the buildings themselves - the notion of exploiting an inanimate object seems strange. Rather, 'ruin porn' exploits the histories or contexts of the buildings, or the viewers of the photographs. Furthermore, I would argue that the categorization of 'ruin porn' must depend largely on presentational context.

Buffalo State Hospital, first floor hallway, 2008. Ruin porn?

I originally published the above image a few years ago, accompanied by a simple descriptive caption, as part of a photoessay on Buffalo State Hospital, designed by H. H. Richardson. I am disinclined to assert that this photograph in this presentational context would qualify as 'ruin porn.' However, if it were presented as part of a "spooky lunatic asylum" photoset on one of the many modern ruins sites found on the internet, and captioned "Wheelchair Hall of Doom," it would take on an entirely different connotation. It is the real and complex history and societal context of the structure that is exploited when photos are presented as such. Some common features of this sort of 'ruin porn' include:

- Editorial impartiality or sensationalism, particularly in fetishizing the eerie or macabre. Instead of providing a neutral viewpoint of a structure with a complex history, the photographer artificially heightens certain properties of a ruin in order to exploit one small aspect of its history. Institutional abandonments such as hospitals and asylums are particularly vulnerable to this cheap sort of exploitation.

- Misleading or falsified historical context. This trend is common among today's dilettantish new generation of "urban exploration photographers," who display photographs of buildings - or even sets of photos from various buildings - under false names, with either absent or misleading contextual information. This exploits the genuine histories of real places, and also exploits the viewer's sensibilities.

Taunton State Hospital, boiler room, 2006. Ruin porn.

- Portrayal of contrived or staged subjects. The photo above is an example - when I came upon the scene, I thought it was an interesting shot, and set up my camera. It was only later that I realized that the artificiality of the shot was repugnant; clearly, the wheelchair had been placed in the scene to make for an "interesting shot." The intentional staging of such scenes is not only exploitative of the real histories of the buildings, which would have included none of these elements, but also of the viewer of the photograph. If the viewer is relatively unacquainted with such places, and is looking at the photograph in order to perhaps learn something about the sort of building being studied, then the effect of the contrivance is downright mendacious.

- Transparent ploys to manipulate a viewer's sympathies. Leary quite rightly berates Moore for photos that "tend towards overwrought melodrama, like the photograph of an abandoned nursing home tagged with a spray-painted slogan, 'God Has Left Detroit.'" An image like this tells us nothing about the building, about its historic context, about any genuine narrative outside of a kid with a can of spraypaint and a sense of irony. This exploits the viewer of the photograph.

Back to Detroit

Leary set out to show that two monographs depicting structural decay in Detroit lack any insightful addition to a narrative of the city, and are merely exploitative in nature. In making his argument for exploitation, Leary sets up a notion of 'ruin porn' that is too broad in scope; numerous times in his essay, he conflates all of modern ruins photography with exploitation. As I've shown, this tautology fails. As hinted at by my analogy to nude photography, ruins photography can certainly be exploitative in nature, but it can also be artistic, documentary, or educational. An analysis of what constitutes "artistic" ruins photography is well outside the scope of this post, but I would hope that it would be obvious that such a thing exists.

There is plenty of gray area surrounding the concept of 'ruin porn', and I have no wish to pass judgment on the works of Moore and of Marchand and Meffre beyond mentioning that they certainly don't have the import of a narrowly-scoped documentary study. Collections such as Payne's aforementioned monograph on New York's substations, Cook and Emond's recent examination of grain elevators in Buffalo, and John Bartlestone's survey of the Brooklyn Navy Yard provide an important historical record - one that would not exist without the efforts of such individuals. They have a certain gravity because they carefully and neutrally document these cultural artifacts.

Because the story of Detroit's decline is well known, and its buildings well documented, the recent books lack the same historic and documentary gravity, although they contain some elegant photographs. A ruins photographer visiting Detroit is akin to a nature photographer visiting the Grand Canyon. A talented lensman is guaranteed to get some technically stunning, but culturally insignificant, photographs of a beautiful and much-studied subject. When Camilo José Vergara began studying the city over two decades ago, it was not the "abandoned building Mecca" that it has become today, and thus Vergara's work has a gravitas that the more recent works do not.

So are they 'ruin porn'? I will provide no answer for this question. If the works in question can be seen to exploit the histories of the buildings they study, or the cultural contexts in which the buildings are placed, or the sensibilities of the viewers, then they are. If they are not guilty of such exploitation, but are merely collections of well-executed photographs, then they belong with the art books. I will leave this determination up to the reader and the viewer.

North Brother Island, cast iron staircase in nurses' residence, 2008. Ruin porn?

All photographs are owned and copyrighted by the author unless otherwise noted.