Republicans control the House of Representatives. Thanks to gerrymandering combined with the increasing concentration of liberal voters in already blue, urban districts, that's about as likely to change after the November elections as is the color of Bernie Sanders' hair (if one white hair reference is good, two is better, right?) That means it will be exceedingly difficult for any president to push through new legislation that would have a truly significant effect on employment or wages.

This is not to disparage any candidate -- putting forth bold plans is important both to inspire voters and to move the Overton Window in the direction of a more proactive role for government when it comes to creating jobs and increasing paychecks for American workers. My point is that the Washington institution most likely to be able to affect jobs and wages is the Federal Reserve. That's where Janet Yellen comes in.

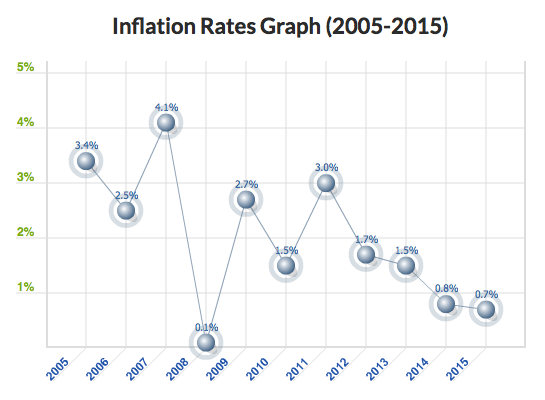

As I wrote one year ago, Yellen's public statements indicate that she does understand the need for the Fed to concern itself with job and wage growth when setting interest rates. This is why many Republicans have slammed her as -- what else -- a partisan. Last fall I urged Yellen to keep interest rates low as long as inflation is increasing at a level below the Fed's target rate of 2 percent per year, which it has been. Even after stripping out the more volatile food and energy sectors -- which the Fed prefers to do -- inflation still only rose 1.3 percent in the previous year (through November, the last time the data was calculated).

Unfortunately, Dr. Yellen and her fellow Fed governors did raise rates on December 17, increasing the federal funds target rate by 25 basis points to a range of 0.25 to 0.50 percent -- the first increase in nearly a decade. They had previously signaled the coming increase, but decided to put off implementing it at its previous two meetings in September and October. The Federal Reserve's policy committee met on January 27 and held rates steady, but reiterated that it nonetheless intended to increase rates "gradually" going forward, and is considering another hike as soon as its next meeting in March.

Trying to read the Fed's tea leaves is no easy task. The well-regarded Binyamin Applebaum, whose New York Times beat includes the Federal Reserve and the U.S. economy, concluded that, compared to last month's Fed statement, "the new policy statement suggested that the Fed's confidence in the economic outlook had since deteriorated." The less confident they are about economic growth, the less likely they are to raise interest rates.

A number of things have happened since the December meeting that may be influencing Yellen's thinking. The day before the December rate increase, the S&P 500 closed at 2,073. As of this writing, it has fallen by just over 9 percent. In six weeks. One other is that Sen. Sanders wrote an op-ed piece in which he harshly criticized the "clear conflicts of interest" created by cozy ties between Wall Street and the Federal Reserve, and called for significant reforms in the way the Fed operates as well as how its board members are chosen. Here's what he had to say about the rate increase that took place a week before his article was published:

Raising interest rates now is a disaster for small business owners who need loans to hire more workers and Americans who need more jobs and higher wages. As a rule, the Fed should not raise interest rates until unemployment is lower than 4 percent. Raising rates must be done only as a last resort -- not to fight phantom inflation.

Sen. Sanders is right. Inflation remains phantom-like, and, although we've had strong job growth the last two years -- the best two-year period this century -- other economic indicators, such as a growth rate for our overall economy (as measured by gross domestic product) of only 0.7 percent annualized in the fourth quarter of 2015, are concerning. For another example, the newest monthly data on spending by businesses on equipment, i.e., non-military capital goods, plunged 4.3 percent in December, while November's figures were revised downward as well. Brian Jones, senior U.S. economist at Société Générale, called it "a miserable report across the board." Say what you really think, Mr. Jones.

We need to keep interest rates as low as possible for as long as possible to allow the recent, decent rise in real wages (they've been going up about 2 percent year-over-year for the past year or so) to continue so that working Americans can finally put the Great Recession behind them -- at least until the next one hits.

Matthew Yglesias offered strong praise for Sanders' proposed Fed reforms, and noted that because the president nominates members of the Fed's board, this is one area where Bernie's differences compared to the eventual Republican nominee -- and also to Hillary Clinton -- matter a great deal.

Whether or not he secures the nomination and ultimately the White House, my hope is that the longer Bernie Sanders remains front and center on the American political scene, the more likely it is that his ideas will influence the path Janet Yellen and the Federal Reserve choose to take.

Cross-posted at Daily Kos.