This is the 10th in a series on "born digital" literature.

Installation view "Electronic Literature and Its Emerging Forms." Melinda White

OK. Some people do read them, even if "read" is not the correct term. Even so, you won't find a single work of e-lit in the Library of Congress catalog. Despite this, from April 3-5, 2013, the most vaunted library in the land hosted "Electronic Literature and Its Emerging Forms" an exhibition of 27 works of "born digital" literature, as well as print antecedents from the collection and hands-on interactive literary exercises for visitors.

Exhibiting literary works, which, for many reasons, are excluded from library collections raises interesting questions -- what qualifies as literature in the age of the Internet and how do we collect, reference, and store it? As Alan Bigelow (whose "This Is Not a Poem" is included in the exhibition) commented in a previous post:

The Internet is full of elit (Facebook is very much digital born and full of multimedia where people tell stories), but elit as those of us in the electronic literature community often practice it is not so easy to find. We are looking for something we think we have defined (or started to, anyway), but in the meantime the whole world has moved ahead with multiple examples of elit that pervade the web and virtually everywhere we look.

Screenshot of Alan Bigelow's "This is Not a Poem"

It is not surprising then that curators, Dene Grigar and Kathi Inman Berens, each begins her curatorial statement by defining e-lit. For Berens, works of e-lit are "stories designed to be read on a computing device and which (quoting N. Katherine Hayles) "work with an important literary aspect that takes advantage of the capabilities and contexts provided by the stand-alone or networked computer."

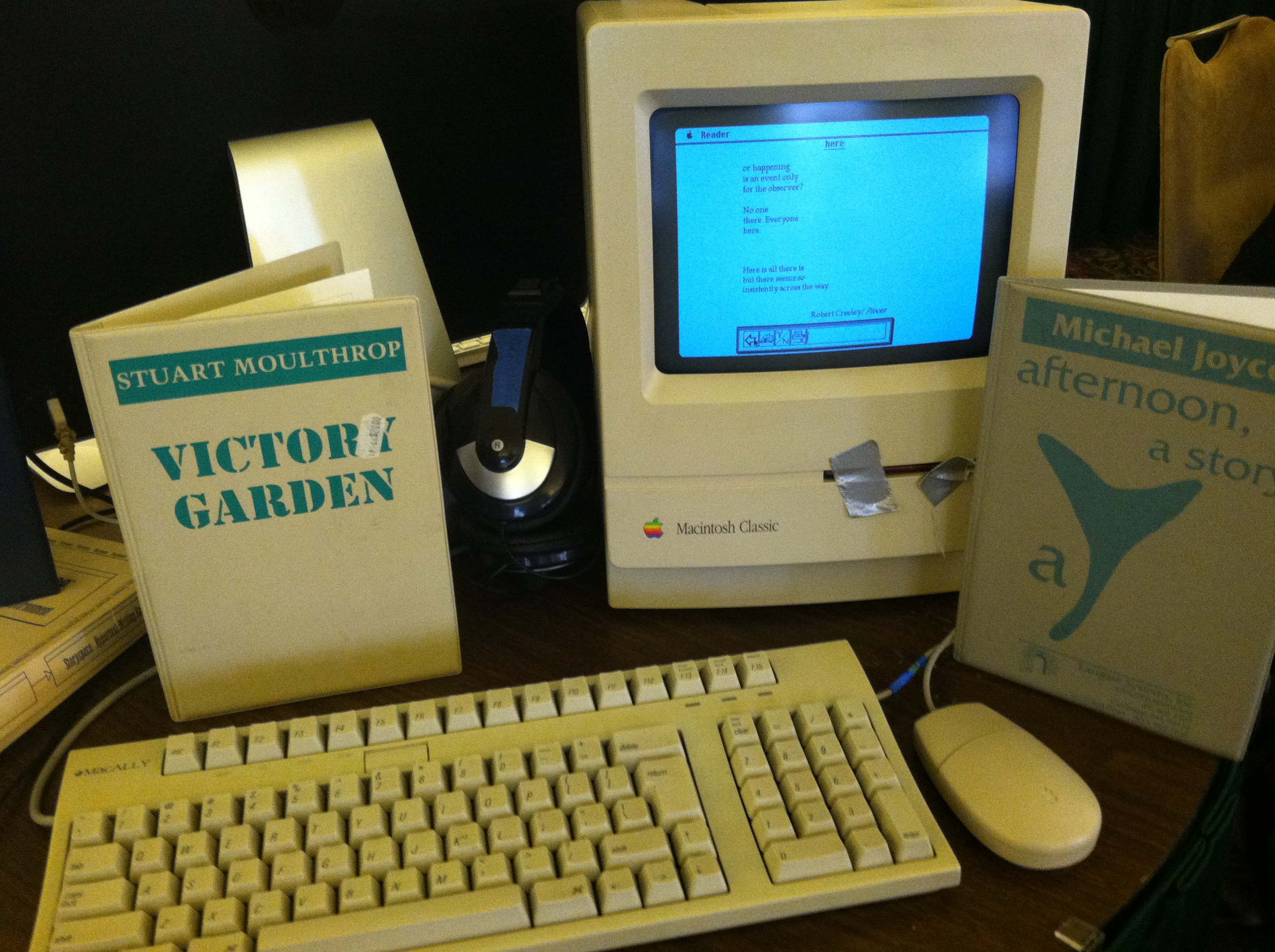

In other words, there is no e-lit without the technology upon which it is made and and experienced. By displaying early works of e-lit on vintage machines, the curators not only draw attention to the issue of preservation, but also emphasize what Berens calls the "fragility" of these works. Like human bodies, "e-literature can break without any violence at all; it breaks just sitting around while new devices, operating systems and software are introduced. E-literature's dependence on machines that become obsolete makes e-lit fragile."

Older readers, myself included, often say that they like the feel of a book in hand, the smell of the pages, the weight of the object, but, perhaps, having not grown up with them, we are simply not accustomed to sensual interactions with newer technologies. As Grigar astutely points out, "so accustomed we have become to the technology of the book and writing that we no longer think of them as technology -- but they are."

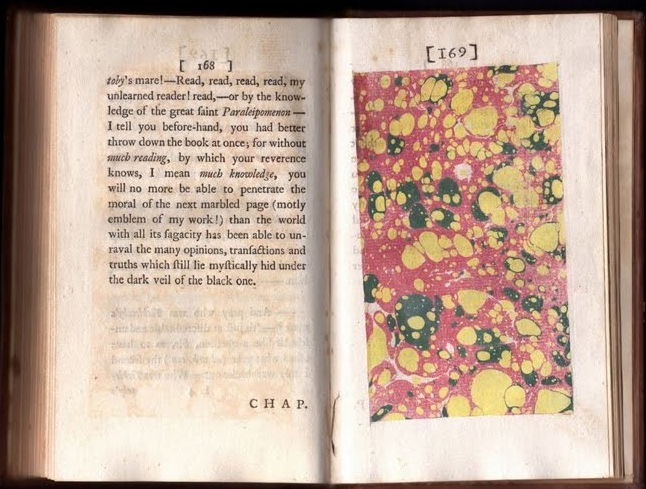

Another interesting question raised by the "context" stations in the exhibition is how do we critique e-lit within the framework of art history? As Grigar notes, e-lit's "history has been inextricably linked to and enriched by experimentation generating from various art forms including literature, the visual arts, sonic art, performance, and cinema, and it is influenced by code and platforms associated with computer science." Being at the Library of Congress, the curators chose to focus on the Library's immense book collection to contextualize the exhibit. For instance, a copy of Tristam Shandy on loan from the Rare Books Collection is used as an early example of remixing source texts and typographic experimentation.

The enigmatic "marbled" page of Tristam Shandy (1759)

In a different setting, the curators could just have well included artworks like Martha Rosler's She Sees in Herself a New Woman Every Day (1976) currently on view at the MOMA or the entire oeuvre of visual artist Sophie Calle to name a few examples.

Because I was not able to see the exhibit, I invited Melinda White who teaches writing with a focus on visual rhetoric and electronic text at Virginia Commonwealth University to share her impressions of the show.

Melinda White:

From April 3 to 5, 2013 the hallowed halls of The Library of Congress housed old-school Macs, typewriters, iPads, zip drives, notable works of electronic literature, and, yes, books in the interactive exhibit, "Electronic Literature & Its Emerging Forms." This groundbreaking exhibit, with guest curators Dene Grigar and Kathi Inman Berens, together with Susan Garfinkel of the library's Digital Reference Section, combined stations of "digital born" literature with context and creation stations that situated the work historically and provided visitors with inspiration and influences of the form. As part of the library's Electronic Digital Showcase, the exhibit was, for the field of e-lit, something akin to being inducted into the hall of fame.

Upon entering the Whittall Pavilion, the hushed marble reverence of the library soon turned electric as 27 works of e-lit sat on café tables down the center of the room like an Italian piazza, structured in ordered stations but set up so that guests could peruse the stations in any order they wished -- similar to the way many works of e-lit are read. Bordering the center aisle, context and creation stations helped visitors understand the historical context and compositional processes of this form of literature.

Mingling with experimental print texts, I recognized an old friend -- "Lexia to Perplexia" by Talan Memmott -- an early online e-lit (originally published in 2000) coded in DHTML and JavaScript. "Lexia," with its creole of English and code, has, to me, always been representative of the symbiosis with the medium that can occur with e-lit reading (and writing). As I walked towards a retro teal iMac I glimpsed more acquaintances -- "Strings" (1999) by Dan Waber and "Faith" (2002) by Robert Kendall -- both significant works of kinetic poetry in the Electronic Literature Collection Volume One.

Still from Talan Memmott's "Lexia to Perplexia"The vintage iMac was home to Myst (1993), a narrative game by Rand Miller, Robyn Miller, & David Wingrove. Sharing a table with Myst was one of my favorite Flash-based works, Ingrid Ankerson & Megan Sapnar's, "Cruising" (2001) -- an incredible melding of audio and visual elements that relies on readers learning to navigate the text to accentuate the coming-of-age metaphor of learning to drive a car.

Still from Ankerson and Sapnar's "Cruising"There is nothing like reading a true hypertext classic on a classic Mac. This old friend was afternoon, a story by Michael Joyce, often referred to as the foremost hypertext fiction, written in 1987 and published by Eastgate. This was nostalgic for me as afternoon was the first hypertext I ever encountered and, upon many re-readings, never continues to astound me with what beautiful writing and over 500 linked lexias of alphabetic text can accomplish. Among other nostalgic technologies were two typewriters, one electric and one manual Corona (a big hit with the younger generation of visitors) on which guests could contribute text.

Materials from The Deena Larson Collection"The Deena Larson Collection," a special addition on the last day, included composition and exhibition materials from Larson's work "Marble Springs." The collection also included floppy discs and their bulkier cousin, the zip drive, which to me symbolize this ever-fluctuating digital world we live in.

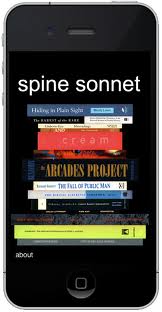

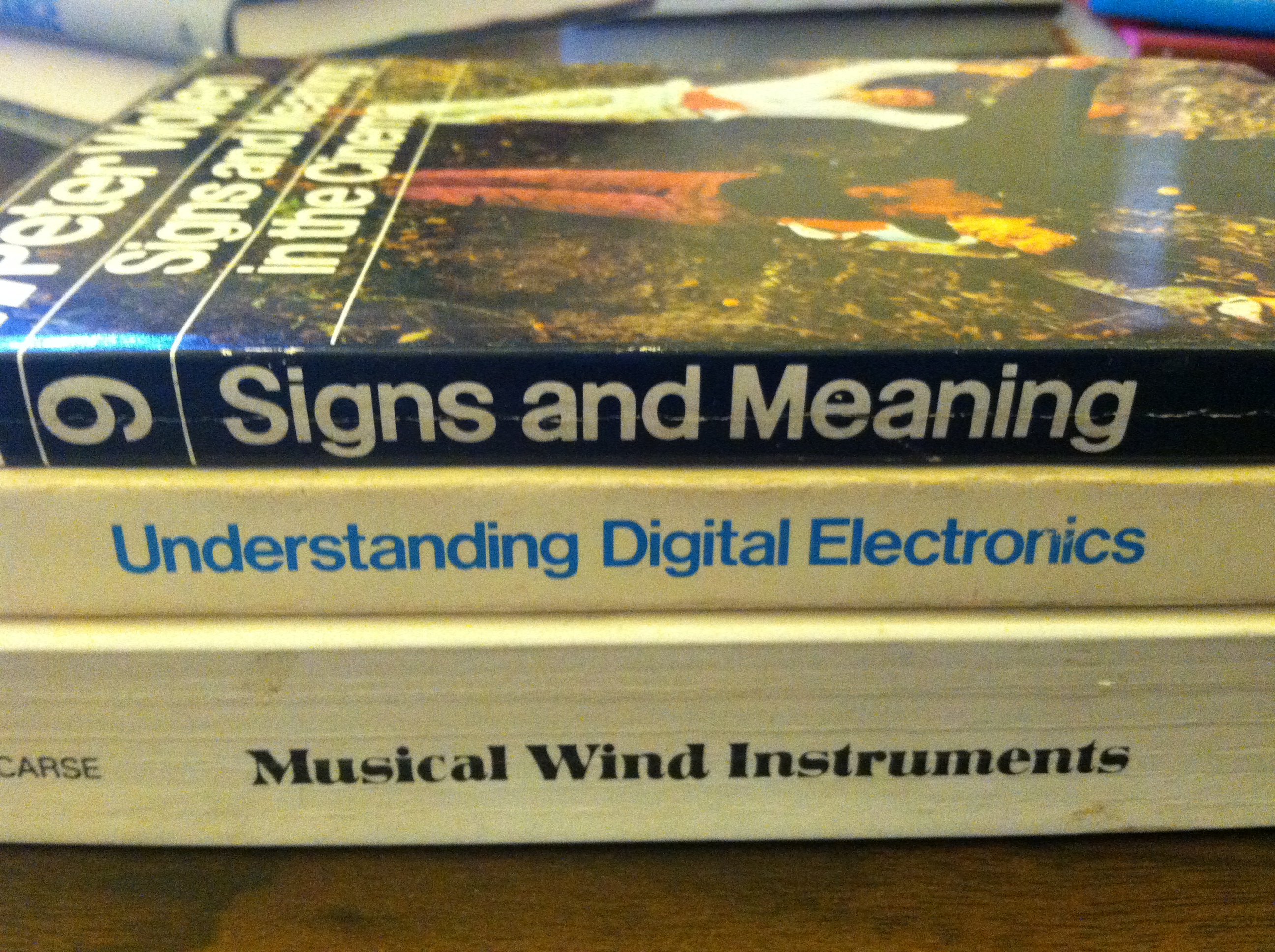

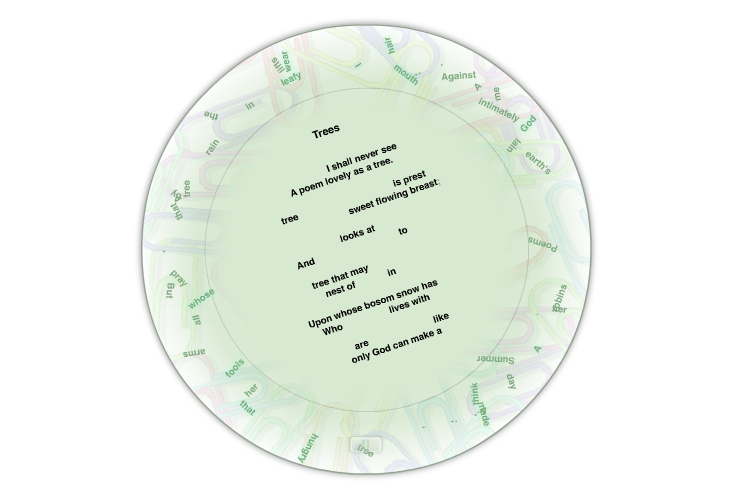

Jody Zellen's app "Spine Sonnet"More recent work included the newly published Electronic Literature Collection Volume Two (2011) -- a USB drive enclosed in a sleek book-like cover. Other fresh, innovative works were Mark Marino's "Living Will" (2012), an interactive fiction, Alan Bigelow's "This is not a poem" (2010), an infinitely re-readable (and enjoyable) play with language, and Jody Zellen's "Spine Sonnet" (2012), which automatically generates sonnets from the spines of over 2500 book titles. An excellent counterpart to "Spine Sonnet" was the Spine Poems creative station which allowed guests to choose from piles of books and stack them to compose their own work of poetry, snap a photo, and submit it online to spinepoetry.com. Mine read: "Signs and Meaning/Understanding Digital Electronics/ Musical Wind Instruments."

Remixing the Books, Melinda WhiteIn “Electronic Literature: What is it?” N. Katherine Hayles states: “Electronic literature tests the boundaries of the literary and challenges us to re-think our assumptions of what literature can do and be.” This is exactly what “Electronic Literature & Its Emerging Forms” provided visitors -- the chance to re-think assumptions and, seeing computer-mediated literature at the Library of Congress, consider what literature can do and the infinite possibilities of what it can be in the future.

BIG NEWS! "Queerskins" my latest multimedia novel has been officially honored by the Webby's as one of the top Net Art sites of 2012! In addition, it will be exhibited at the 5th International Digital Storytelling Conference in Ankara, Turkey in May.