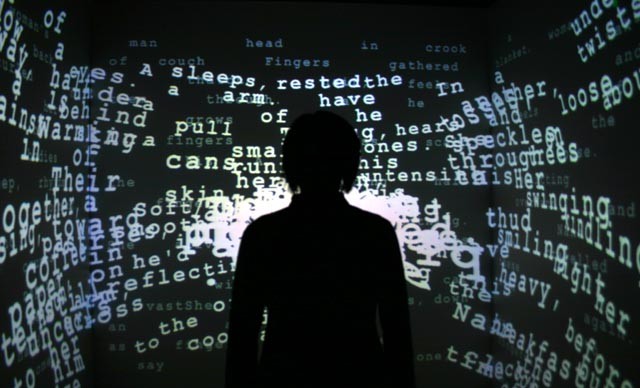

Installation view of Noah Wardrip-Fruin's "Screen" from the Second Electronic Literature Collection

"The slow erosion of a reading public that began when the Lumiére brothers invented the movie camera has accelerated. Although educators and publishers bemoan the loss (surely the younger generation would rather surf the Internet or listen to their iPods), this trend does not herald the end of literature, but rather its inevitable transmutation."

I wrote that in 2007, when I was unsuccessfully trying to interest a literary agent in my new multi-media project Reconstructing Mayakovsky. As any writer or artist will tell you, you don't make the work you want to make, you make the work you have to make. So it was that I found myself explaining why my "novel" included a hand-drawn animation, a manifesto, and a real-time Google image search engine for words like "hope" and "evil". At the time, I was not even aware that other people were creating what has come to be known as electronic literature. Five years later, most lovers of literature have never read a "born digital" work of fiction. In fact, it is only recently, with the "publication" of the iPad app-based novel The Silent History www.thesilenthistory.com by former McSweeney's alums that this kind of writing is finally getting attention in the popular press (albeit more for its cool use of technology than for being an evolved literary form.)

In this series of posts, I'll explore the history of e-lit, how it differs from e-books, and showcase a range of work from Young-hae Chang Heavy Industries' graphic animations to J. R. Carpenter's game-based stories. I'll talk to e-lit pioneer Mark Amerika as well as more recent converts, Paul La Farge and Eli Horowitz, novelists who have embraced the creative potential of born digital fiction. I hope that, by the end, readers will see that electronic writing does not herald the end of literature, but rather the birth of a new art form that can co-exist with more conventional modes of writing.

Eventually, I did manage to get Reconstructing Mayakovsky "published." The animation, done in collaboration with Pelin Kirca and Itir Saran, was shown in eight short film festivals around the world. The site was a jury pick for the Japan Media Arts Festival in 2010 and was selected for the second Electronic Literature Collection put out by the Electronic Literature Organization in 2011.

The Electronic Literature Organization, currently headed by Nick Montfort at M.I.T. "was founded in 1999 to foster and promote the reading, writing, teaching, and understanding of literature as it develops and persists in a changing digital environment," as it states on the website. I recently had the opportunity to interview Nick, a well-respected interactive poet and writer, about the origins of e-lit and its evolution over the last few decades. His responses are below.

IS: How does electronic literature differ from an e-book?

NM: The e-book is a publisher-driven concept for the digital distribution, marketing, and sales of things similar to print books. Electronic literature stems from the innovation of authors and artists and the impulse to bring the literary arts into the digital realm, often in ways that are radically different from print books.

IS: The news media seems to think that the "publication" of Silent History represents the first time people have used technology to create interactive fiction. Clearly this is not the case. Can you briefly describe the origins of interactive fiction?

NM: I think it's great that well-publicized projects introduce people to electronic literature. There is a large, secret, and perhaps silent library of work available. Interactive fiction (began) in 1976 when Will Crowther created a simulated textual world that could be controlled by short typed commands. Later, Don Woods (expanded it to create) the classic program "Adventure" on a minicomputer. An outpouring of successful commercial work (such as the Infocom-published "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy") came soon after. By the late 1980s, as commercial text-based interactive fiction was starting to wane, hypertext fiction, beginning with Michael Joyce's "afternoon, a story," was circulating and inspiring discussion and projects within the academy. Then there were projects on the Web, in HTML, Flash, and other systems -- from the sprawling collaborative novel "The Unknown" to the somewhat Myst-like "Reagan Library" by Stuart Moulthrop. I describe this in a good bit of detail in my book "Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction." http://www.amazon.com/Twisty-Little-Passages-Approach-Interactive/dp/0262633183

IS: Can you give us a couple of your favorite examples of interactive fiction (free) that will demonstrate the range of work being made?

NM: I can, but it's a bit like asking me to recommend a poem -- there are a huge number and a wide range of good options. Emily Short, Adam Cadre and Andrew Plotkin are three of the top authors. And I'm restricting myself to interactive fiction specifically here, although of course I suggest The Electronic Literature Collection http://collection.eliterature.org/1/

http://collection.eliterature.org/2/ for many different sorts of electronic literature.

IS: Electronic literature can cross so many disciplines visual arts/literature/performance/sound art --- who is qualified to critique these works?

NM: People who make a connection and actually do the reading, work the interface, and get something out of the experience (whatever their overall assessment of a particular piece). Beyond that, those expert in visual art will of course be able to better critique the visual art aspect of a multimedia piece, and so on. Those who have a practice in authoring electronic literature have some advantage in understanding the process, although "pure" critics can make (and have made) very useful contributions, too.

IS: Do you think this cross-disciplinary aspect is what has lead to the varied patterns of distribution? For instance, you have people like Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries (whose work I saw for sale at last year's Frieze Art Fair in NYC) to people who make free online games to full-length novels that Eastgate sells on CD.

NM: Some of the differences are due to gallery contexts being of interest to some, free circulation online being of interest to others, and some other distribution models being available. But there are also technology changes and different sorts of physical media over the years. The floppy disk was a reasonable distribution method for software for a while, and then the CD-ROM, but these are less plausible today as the main, or certainly the sole, means of getting bits from place to place.

IS: How do we get these works out to a more general audience? From my perspective, being outside academia, it seems that primarily scholars, other e-lit writers, educators, and tech people know about the Electronic Literature Collection.

NM: In part, it's done a few people, or one person, at a time as we show the electronic literature we love to people -- in readings that I do myself and that I host in the Purple Blurb series at MIT http://nickm.com/if/purple_blurb/, for instance, or sitting at a coffeehouse with someone. (By the way, people do come from outside MIT, and outside academia, to enjoy the Purple Blurb readings.) The Electronic Literature Organization is an attempt to make this work available more broadly and to bring attention to it, though the Collection, our conference, our Electronic Literature Directory, and our site, among other activities. Publishers, bookstores, and libraries have been important institutions in helping literature take shape in our culture. But e-lit isn't very connected to any of these institutions. The Harvard Book Store is a great place for paper-based publications, but there are no staff picks of electronic literature and no readings of electronic literature that they host.

We're working on (changing) that. The Hayden Library recently hosted an exhibit, Games by the Book, http://trope-tank.mit.edu/games_by_the_book/

that the ELO co-sponsored, and the Cambridge Public Library has hosted a reading of interactive fiction, both of these thanks to the work of Clara Fernandez-Vara. We do want to take the best aspects of literary institutions such as these along with us as we bring literature through the network and into the computer. It will take personal sharing and enthusiasm as well as the work of organizations and institutions. But the opportunity is too great to miss.

This is the first in a series of posts on electronic literature. Check back in for more in the coming weeks.