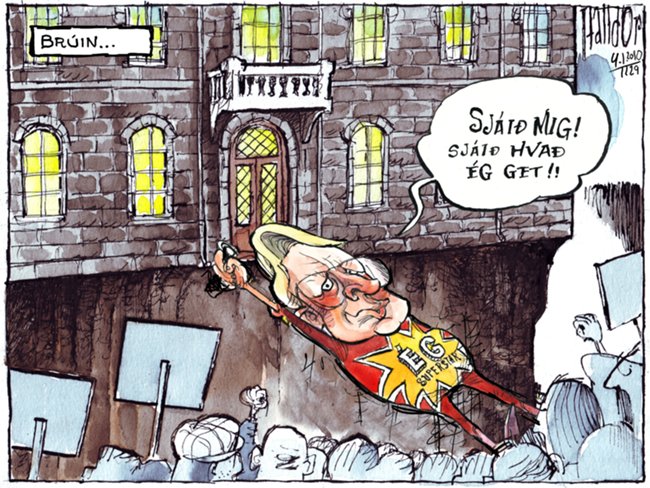

Since Iceland's president, Ólafur Ragnar Grimsson, announced his refusal to sign the IceSave compromise worked out December 30, 2009, many at home and abroad have held him up as some sort of hero standing up to heartless bankers and fighting injustice in the capitalist system. Unfortunately, Ólafur Ragnar is merely protecting his Icelandic oligarch friends against actions by the British and Dutch authorities to recoup funds lost by depositors -- individuals, pension funds, municipalities -- in their countries as a result of the fraud and incompetence of Icelandic regulators and bankers. "Look at me! Look what I can do!" Political cartoonist Halldór Baldursson's take on Ólafur Ragnar's veto. mbl.is

"Look at me! Look what I can do!" Political cartoonist Halldór Baldursson's take on Ólafur Ragnar's veto. mbl.is

Here are the facts:

After the conservative Independence Party implemented its libertarian policies, the Icelandic banks were privatized and underwent an explosive expansion in the 2000s. They accomplished this by leveraging saving accounts and pension funds in Iceland, taking huge loans that they then relent themselves to acquire foreign banks and other assets and created fake capital by trading assets amongst themselves at inflated values (as one expert described Icelandic banking: You have a dog, and I have a cat. We agree that they are each worth a billion dollars. You sell me the dog for a billion, and I sell you the cat for a billion. Now we are no longer pet owners, but Icelandic banks, with a billion dollars in new assets).

The sudden presence of vast sums of money quickly corrupted the political and regulatory systems, and the Icelandic regulators did not examine the banks' business practices in great detail, but rather served as facilitators, and the politicians -- including Ólafur Ragnar -- served as cheerleaders.

Although several reputable experts had warned that the banks' finances were on questionable footing, the void behind their facades did not become evident to all until Lehman Brothers' collapse in 2008. Once Landsbanki became aware that its collapse was imminent, it attempted to move depositors' funds from the United Kingdom and the Netherlands to Iceland in order to cover its domestic depositors. After Iceland's finance minister, Árni Mathiesen, bluntly told Alistair Darling that Iceland would only provide depository insurance for depositors in Iceland, the British froze Landsbanki's British branches and insisted that the Icelandic government honor its commitment under the EEA treaty to treat their citizens on an equal basis.

The British and Dutch governments then approached the Icelandic government and offered to lend it the money needed to pay the British and Dutch depositors the amounts called for by the EEA treaty. Although Iceland initially refused, it eventually agreed to these terms when it became obvious that nobody was going to deal with them until the matter was resolved. Iceland's parliament -- the Alþingi -- passed a bill approving the deal in August 2009 but added provisions limiting the amount it would pay in a given year and calling for the loan to be written off if it was not paid off in twenty years.

The bill that Alþingi passed last week was the result of lengthy negotiations with the British and the Dutch. Nobody wanted to pay the money which represented 40% of Iceland's GDP and was desperately needed at home, but the ruling left-center coalition determined that the alternative would be worse. Ironically, the Independence Party MPs adamantly opposed the deal, even though their party was primarily responsible for this mess in the first place.

While Icelandic legislators were trying to hammer out a deal that would keep the country from being labeled a pariah state by the IMF and ratings agencies, Ólafur Ragnar never uttered a peep about rejecting the bill. The Icelandic president is essentially a figurehead, and the constitutional power of veto had been used only once in the history of the republic. No one in Alþingi had any reason to suspect that he would not sign the bill.

If the referendum on IceSave results in the bill's rejection, there will be a strong pressure on the government to resign and call for new elections. Given the Tea Party mood in the country these days, this will almost certainly place the conservative parties back into power.

The movement to reject the IceSave bill was largely demagogic politics by the former ruling conservative coalition. Is it any coincidence that the petition presented to Ólafur Ragnar asking him to veto was the work of Magnús Árni Skúlason, a former Progressive Party board member who was forced to resign from the Central Bank after it became known that he was aiding and abetting violations of the country's currency laws? Is it any wonder that the current head of the Independence Party has done a 180 degree turn on his position on IceSave? Should we be surprised that many former Independence Party supporters and sponsors are expected to be indicted soon for their roles in the fraud underlying Iceland's burst bubble? Does it stretch the limits of credulity to discover that Ólafur Ragnar himself became very close to the oligarchs who profited from the banks?

It would have been courageous for Ólafur Ragnar to have called on the banks to rectify the weaknesses identified by Danske Bank in 2006. It would have been courageous for him to have denounced the Icelandic public's unsustainable consumerism. It would have been courageous for him to have questioned the "irrational exuberance" of his banker friends instead of cheerleading their orgy of conspicuous consumption. It would have been (at least somewhat) courageous for him to have spoken up against Alþingi's proposed course before reading opinion polls and receiving the petition.

This is not courageous. Telling ordinary depositors in foreign countries that they were fools to have trusted Icelandic bankers is not courageous.

At this point, we can only hope that the politicians who pushed the IceSave bill through will take to the airwaves to convince the Icelandic people that, although they may not like paying their debts, the consequences of not doing so would be much worse. Although the August IceSave bill remains in effect, it is extremely doubtful that the UK and the Netherlands will accept its terms and permit the IMF to release badly-needed funds to Iceland.

The full consequences of the president's decision have yet to be felt, but two of the three rating agencies immediately lowered Iceland's sovereign ratings to junk bond status, and the third will probably do so soon. Certainly, Iceland will not be allowed into the EU until this is resolved, and they may be booted from the EEA.

The history behind Iceland's fall is already being rewritten, with the architect of the whole Icelandic money mirage and chair of the Central Bank during the relevant period -- Davíð Oddsson -- now serving as the editor in chief of the country's largest newspaper.

Iceland must focus on rebuilding its reputation as a trustworthy business and diplomatic partner in the community of nations and direct its energies on resolving the issues vital to its survival as a democracy: abroad by repairing our relations with the world community and the nations hurt by the crimes of our financial and economic elite, and at home by thoroughly investigating, prosecuting and punishing the criminals.

If the criminal and regulatory investigations currently underway are not completed, the individuals responsible for nearly destroying their country may be exonerated; the whole sorry mess will be whitewashed, and any lessons we might draw from this painful experience will go down the drain -- along with any hopes of a functional, just democracy.