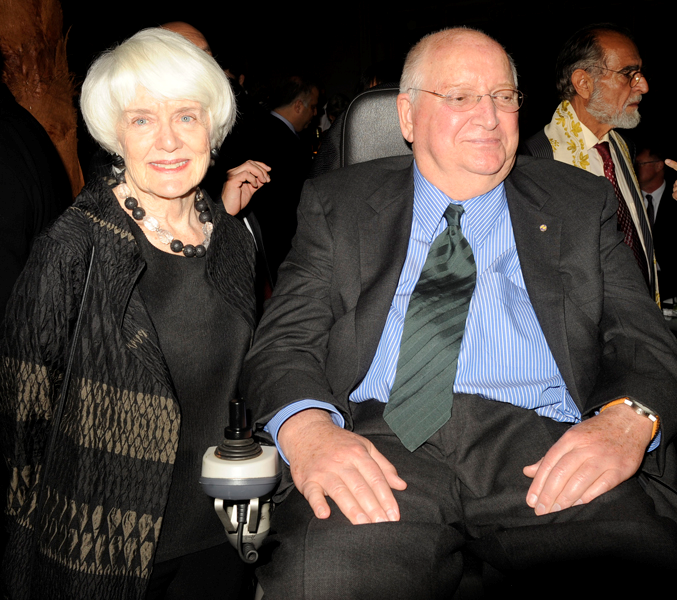

A pair of epiphanies decades ago guided Betsy Rogers and Michael Graves along paths that led last weekend to two of the most coveted awards in classical design.

Graves traces the honor of winning the Richard H. Driehaus Prize for Classical Architecture back to his 1960 Prix de Rome fellowship from the American Academy in Rome.

"When I was in school for my master's degree at Harvard, we didn't discuss Palladio," the architect says. "We were left dumb to history and architecture -- it was an ahistorical time, started by Gropius, really."

When he got to Rome, he began to learn in a new way, inspired by what he saw and whom he met. In school, he'd learned to design a building in context, to use the architectural language of its neighbors. But in Rome, things were different. "The buildings did all kinds of things to the buildings next to them -- they'd gobble them up," he says. "And it was so much better."

Every night at dinner, the Rome fellows were joined by scholars, musicians and historians who'd come in and talk about what they'd achieved that day. It all may have been glorious, but Graves' participation was limited. His own palette was thin, because he didn't know much classical architecture.

And so he began a new narrative arc, created through drawing, text and design. "I started writing the storytelling context of architecture, reinvigorating my own palette from Rome," he says. "And I've never stopped."

His work doesn't mimic the work of Palladio or the architecture of Athens and Rome, but it's clearly informed by the classical principles of balance, harmony and symmetry. And he continues to experiment with how the profession might move forward as he employs them.

"We have to live in our times, but apply these principles," says Michael Lykoudis, dean of the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture, which has presented the Driehaus Prize annually for the past 10 years. "Classicism is an imitation and idealization of nature. Modernism is an idealization and representation of an industrial culture."

Betsy Rogers, the 2012 Henry Hope Reed Laureate, an award also funded by Richard H. Driehaus and presented by the University of Notre Dame, found her calling by reading a guidebook for Central Park written by Henry Hope Reed as she strolled though Manhattan's grand but worn-out green space in the mid-'70s.

"Henry Hope Reed was on the side of angels at a time when the architecture profession was going in a different way, thinking that innovation meant modernism," Rogers says today. Because of the 97-year-old Reed, she dedicated herself to preserving Frederick Law Olmsted's best-known work.

"[Reed]'s the one who carried the flame of the classicists when modern architecture was polemical in discarding the past," she says."He wrote and spoke back in the '60s and railed against the destruction of Penn Station. It was the beginning of the landmarks movement."

A writer and landscape preservationist who's currently president of the Foundation for Landscape Studies, Rogers served as New York's first Central Park administrator and as the founding president of the public/private Central Park Conservancy. In those roles, she led the park's restoration and preservation from 1979 to 1996. It's now enjoying what some call its golden age.

"In 1975 I was a little missionary for this public/private partnership," she says. "We started by raising $150 million, and now we've raised $500 million. The citizens of New York have really stepped up to the plate. It's strengthened beyond my time -- the conservancy is now an institution."

Rogers now writes and lectures about the cultural meaning of place in human life, and is the author of Landscape Design: a Cultural and Architectural History. It's become the book to teach from in universities and schools across the nation.

She and Graves represent the best of what classicists can symbolize in 2012: They're interpreting age-old, proven values, in new ways.

"We want to reposition the notion of what classicism is, beyond columns and homes for rich people," says Notre Dame's Lykoudis. "We want validity beyond classicists."

Says Graves: "Architecture is humanistic on one hand like Palladio or myself, and technological on the other hand, like Richard Rodgers or Norman Foster."

And the Driehaus Prize counters the weight of the Pritzker, so often awarded to the modernist of the moment.

"It's (the Pritzker) one of those things that the public can't engage because it's cutting edge, and uneven," Graves says. "Could Aldo Rossi or James Stirling win it today?"

But for the architect who's as comfortable designing balanced monuments the size of the Humana Building in Louisville, Ky. as he is with sympathetic homes for wounded warriors at Fort Belvoir, Va., the Driehaus Prize is freighted with meaning.

"With people's introductions and what was said about me, it brought tears to my eyes," he says. "It's just very nice that people recognize my architecture, whatever it is."

For more by J. Michael Welton, go to http://architectsandartisans.com

For more on the Driehaus Prize, go to http://architecture.nd.edu/events/driehaus_prize.aspx