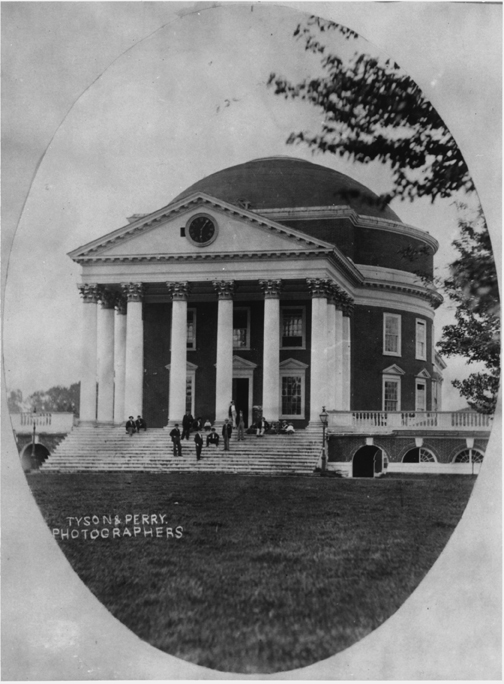

Pity the architects who've tried for almost 200 years to follow the genius of Thomas Jefferson at the University of Virginia.

Their efforts bring to mind Fitzgerald's remark regarding the dearth of second acts in American lives. In Charlottesville, though, we're talking about the life of one of the nation's finest master plans -- and the mostly lackluster structures that have proliferated around it.

At the time of its design, the spirit of Jefferson's 19th-century "academical village" was innovative, experimental and environmentally sensitive. Those who've come after have more often deferred to that spirit rather than tried to keep up with it.

"Jefferson created an unbelievably powerful landscape," said Daniel Bluestone, director of the Historic Preservation Program at U.Va. "There's just this stunning resonance in the way the buildings intersect with the land."

Bluestone devoted a chapter in his new book, Buildings, Landscapes and Memory, to the banality of the buildings that followed the master in Charlottesville. It's titled "Captured by Context," and it explores the relationship between historic sites and adjacent development.

When Jefferson designed the school, it was to house 10 professors and 220 students. Today, those numbers have increased by a hundred fold. The result is a scale and density that he hardly could have imagined.

"McKim Mead & White's strategy was to go monumental, but small in deference. They tucked buildings into the landscape so as not to trump or overtype existing buildings," Bluestone said.

Others followed their cue, using Jefferson's bricks and columns in a dizzying array of design aesthetics that disappoint more often than delight. Some serve as unfortunate testaments to the fact that it's the music, rather than the words, that's most important in architecture. "Jefferson had a huge sense of the combination of land and buildings, and when you reduce it to red brick and white columns, it just doesn't work," Bluestone said.

But there are notable successes too. Gilmer Hall, designed and built by Louis Ballou from 1959 to 1963, is a modern and dynamic essay, with a clever comment on the university's serpentine walls. The original Campbell Hall by Pietro Belluschi and Sasaki, Dawson and Demay, 1965-70, also paid attention to earlier themes.

"Like Stanford White before him, he paid special attention to the character of the brickwork, in order to harmonize his walls with those with the original parts of the university," Bluestone writes of Belluschi. Also successful are additions to Campbell Hall, the most recent being the East Wing by W.G. Clark in 2008.

The school flirted with Louis Kahn for a Chemistry Building, but dropped him.

It solicited designs from architects like Stubbins, Polshek, Stern and Graves, with varying degrees ofsuccess.

"The real problem is that they keep trying not to do density," Bluestone said. "With 20,000 students and several thousand faculty, it's hard to do density and pretend you're still in the midst of a rural community."

Perhaps his most telling point, though, is contained in the last sentence in the last paragraph of the chapter. "Excellence, in the end," he writes, "should inspire excellence."

In Charlottesville, that's happened only rarely in the past two centuries.

For more on Daniel Bluestone and "Buildings, Landscapes and Memory," go to http://books.wwnorton.com/books/Buildings-Landscapes-and-Memory/

For more by J. Michael Welton, go to http://architectsandartisans.com

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

It's Another Trump-Biden Showdown — And We Need Your Help

The Future Of Democracy Is At Stake

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

Your Loyalty Means The World To Us

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

The 2024 election is heating up, and women's rights, health care, voting rights, and the very future of democracy are all at stake. Donald Trump will face Joe Biden in the most consequential vote of our time. And HuffPost will be there, covering every twist and turn. America's future hangs in the balance. Would you consider contributing to support our journalism and keep it free for all during this critical season?

HuffPost believes news should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay for it. We rely on readers like you to help fund our work. Any contribution you can make — even as little as $2 — goes directly toward supporting the impactful journalism that we will continue to produce this year. Thank you for being part of our story.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

It's official: Donald Trump will face Joe Biden this fall in the presidential election. As we face the most consequential presidential election of our time, HuffPost is committed to bringing you up-to-date, accurate news about the 2024 race. While other outlets have retreated behind paywalls, you can trust our news will stay free.

But we can't do it without your help. Reader funding is one of the key ways we support our newsroom. Would you consider making a donation to help fund our news during this critical time? Your contributions are vital to supporting a free press.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our journalism free and accessible to all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you'll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.