Until Saturday, Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman, boss of the Sinaloa Cartel, was the most powerful and feared drug lord in Mexico. Based on intelligence that El Chapo had, after 13 years in hiding, started to come down from his mountain hideouts, a joint operation run by Mexican marines and DEA officials from the United States was able to capture and arrest El Chapo. The world is celebrating. "This is the most significant arrest of a drug trafficker in decades," Mike Vigil, the former head of international operations for the DEA, told Time magazine. But is this really cause for celebration? A meta-analysis of 306 studies by the Urban Health Research Initiative, found that analogous to the case of alcohol prohibition in the United States, strict enforcement of drug policies in Latin America has only increased violence and organized crime.

Four causal pathways support this logic. First anti-drug policies increase functional specialization. Maher and Dixon in The Cost of Crackdowns explain that

Intensive policing encourages the development of more organized, professional and enduring forms of criminality [by] increasing the complexity and sophistication of the market, [which] encourage[s] functional specialization and hierarchical differentiation.

Second, anti-drug policies increase territorial disputes. Professor Goldstein at the University of Illinois writes that drug enforcement disrupts drug markets, leading to an increase in violent crime as drug dealer's fight over turf and market share.

Third, crackdowns create geographic stratification. Professor Rasmussen of Florida State University finds that increased drug enforcement forces cartels to spread out, increasing number of cities where they wreak havoc.

Fourth, crackdowns result in the relocation of police resources. Benson, President of the University of Colorado, writes that as the police re-allocate their resources to deal with drug crimes, criminals commit more violent and property crimes because they believe that the police are focusing on "other criminals." He shows that increasing drug arrests were associated with a fivefold increased risk of violent and property crime, even after controlling for confounding variables.

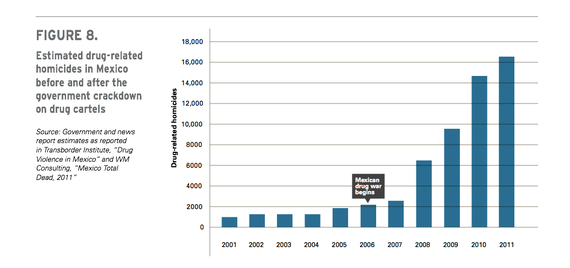

These findings are empirically quantified. Kevin Casa of The Brookings Institute writes that "35,000 people may be dying in Latin America yearly as a result of the black market in drugs that the current policies render into existence." Since the Merida Initiative was initiated in 2007, Mexican violence has increased eightfold: In 2007, there were 2,680 drug-related homicides in Mexico, this jumped to 6,837 in 2008, 9,614 in 2009, and 15,413 in 2010, according to data released by the Mexican government. Drug-related homicides increased 60 percent in 2010, and 11 percent in 2011. On a whole, prohibition-related violence has led to the death of more than 60,000 people since 2006, according to the Drug Policy Alliance, and has spread from roughly 46 municipalities in 2007 to 225 today. Meanwhile, human rights abuses have increased by 900 percent.

Decapitation of cartels leaders has been a major part of U.S. anti-drug strategy, but cartels have reacted to the loss of their leaders by fragmenting, rather than disappearing. In 2006, there were just six major cartels operating in Mexico; by 2010 that number had doubled, according to Nexos magazine. Local trafficking organizations exploded during the same time frame, from 11 to 114.

This violence is spilling over into the United States: According to the U.S. Justice Department, Mexican cartels now operate in over 1,000 US cities. Sylvia Longmire writes for CNN that the tens of thousands cartel members in America are a bigger national security threat than even terrorism. Esquire magazine quantifies the current American death toll due to the war on drugs at 6,487.

Worst of all, anti-drug crackdowns are failing.

Heroin: According to six former Presidents and other world leaders, worldwide supply of heroin has increased by

more than 380 percent in recent decades, from 1000 metric tons in 1980 to more than 4800 metric tons in 2010. This increase coincided with a 79 percent decrease in the price of heroin in Europe between 1990 and 2009.

According to the Drug Policy Alliance

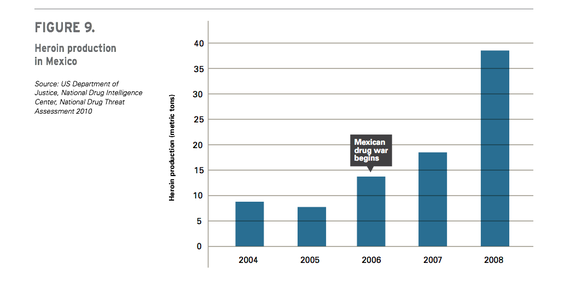

similar evidence of the drug war's failure to control drug supply is apparent when US drug surveillance data are scrutinized. For instance, despite a greater than 600 percent increase in the US federal anti-drug budget since the early 1980s, the price of heroin in the US has decreased by approximately 80 percent during this period, and heroin purity has increased by more than 90 percent. Recent estimates suggest that Mexican heroin production has increased by more than 340 percent since 2004.

Cannabis: According to the Report of the Global Commission on Drug Policy,

when cannabis, the drug that has been the central focus of the US government's decades-long war on drugs, is considered, the results have been the same. Specifically, the potency and inflation-adjusted price of cannabis in the US has declined by 33 percent while its potency has increased by 145 percent since 1990.

In fact, the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse has concluded that

over the last 30 years of cannabis prohibition, the drug has remained "almost universally available to American 12th graders, with between 80 percent and 90 percent consistently reporting that the drug is 'very easy' or 'fairly easy' to obtain.

Cocaine: The Global Commission on Drug Policy's report furthers that

through a variety of initiatives, the United States has directed considerable resources toward disrupting the cocaine trade. Plan Colombia, for example, was a multibillion dollar investment in the eradication of coca crops in Colombia through aerial and manual eradication, military training and support, and other means. Nevertheless, despite steady increases in the U.S. budget for international supply reduction and counter-narcotics activities, the purity of cocaine has remained persistently high, while the purity- and inflation-adjusted price of cocaine in the U.S. has concurrently dropped by more than 60 percent during this period.

In conclusion, killing kingpins like El Chapo and cracking down on drug cartels only increases violence and increases the quantity of drug trafficking.