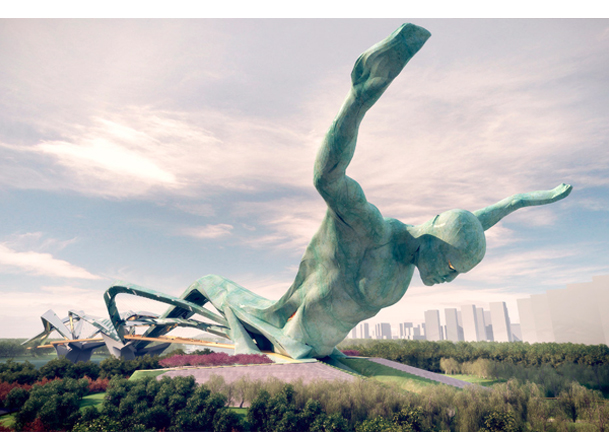

The Titan. Photo Courtesy of BAM.

Globalization is a prevalent theme these days. People can travel to opposite points in the world in less than a day, and can send emails to opposite points in the world in less than a second. Many ways of life are converging like never before.

As one assesses the growing connectivity and increase in business and design standardization, it becomes more evident that even amidst this unprecedented boom in technology and resulting global homogenization, there's still so much variety to be found. These days architectural design is a global condition whereby American architects are designing buildings in China and vice versa. And even though the function of the architect is largely the same everywhere in the world, the business of design most certainly is not.

I'd like to share the story of a design firm in China, Ballistic Architecture Machine (BAM), founded by three architects born and educated in the United States. BAM recently participated in a competition in China for a 100m tall monument and 350m long pedestrian bridge that crosses an offshoot of the Yangzte River in Nanjing's new CBD district named HeXi. Unlike competitions in Western countries, this one wasn't about who would win or lose, or who would be paid or not paid, but it was about collecting as many ideas as possible. Is China doing something smart hoarding all of this design intellectual property?

The story of this project unveils the unmistakable truth that the business of design in China is completely different than outsiders generally perceive. It is a business structure that has its pitfalls, but likewise its unsung benefits. It is a model that encourages designers to output more profound and experimental design catalyzed by the prevalence of competitions, and allows clients to select from the best of the best, without having to declare one design as the singular solution. As globalization continues it is certainly a model that Western designers and businesspeople will have to learn to become comfortable with.

Jake Walker, one of BAM's founders was kind enough to spend time with me on the phone and further corresponded via an email exchange.

Allison Macneil Dailey, Daniel Anthony Gass, and Jacob Schwartz Walker. Photo courtesy of BAM.

Jacob Slevin: Please briefly describe the Nanjing Youth Olympic Games Monument and Bridge Competition.

Jake Walker: Nanjing is host to the Youth Olympic Games in 2014 and the city is using that as a way to spark development in its newly planned CBD. The site of the competition is at the end of the district's major axis, which runs East-West and culminates as a park along the river's edge. The buildings directly adjacent to the competition site on the north are two towers connected by a podium being designed by Zaha Hadid.

BAM assembled the professional team of specialists, which included Mathew Vola and Craig Gibbons of Arup's Brisbane office, an engineering team from BIAD headed by Chen Bing Lei, and a specialist bridge engineer and contractors from CERI.

JS: Competitions are expensive enough with a single entry. Why two entries?

JW: We had two very different schemes, and each scheme took a very different approach regarding the site, as well as different interpretations of what monuments should be. Clearly the most obvious architectural program was the bridge, but other than that, the program of the monument is fairly up for interpretation, and it was these interpretations that resulted in our proposing two drastically different schemes.

I should first emphasize that it was a requirement of the competition to provide two schemes, but this was to satisfy bridge requirements in which the governing body was not sure if the bridge should be operable or fixed. Therefore, the two schemes were meant to provide flexibility, not to present entirely disparate positioning statements all together.

BAM's Nature Gate scheme is really a more landscape based approach challenging how giant art pieces should fit within the urban condition. Thus, the monument itself should be a way in which one's surroundings are enhanced by the existence of the piece. One of the best examples of this kind of art is the Sky Gate by Anish Kapoor in Chicago's Millennium Park. Sky Gate is absolutely magnificent stand alone, but it is less about itself and more about its urban context, enhancing one's experience of the city and its surrounding.

Nature Gate attempts to achieve a similar relationship with its surroundings, functioning in one axis as a gateway, interacting with the urban condition, and along the other axis interacting with the more natural environment of the river front, cutting off the experience of the city. Thus, the function of Nature Gate is to enhance one's surroundings in new and more directed ways.

The Titan scheme is very different and certainly less sensitive. Its function or purpose is much more elemental. Its purpose it to connect people to the spirituality and intensity of the human body. People, mankind, are enthralled by watching other people achieve physical prowess. It makes all of us feel more human. This is why people love to watch competitions, much like the Olympics. In the end, the Olympics or any other competition, game, or race, is not in fact about who wins, or which country has the most gold medals, rather such events accentuate that we all feel a sense of connection to those who express their ambitions through their bodies. It reminds us of our ancient past, living in caves, running in fields, and it also gives us hope for the future of humanity, that we can become faster, stronger, smarter, jump higher and swim farther. The expression of our physical self through sport and play connects us to the fundamentals of our existence.

JS: What was your favorite moment of the experience?

JW: BAM loves making physical models and it's really something that everyone in the office can get involved in. Although it was truly exhausting, the final push to get the physical models done and out the door was a really fun experience, and it was such group effort that it really helped to build camaraderie.

Photos courtesy of BAM.

JS: Now that it's over, would you do it again?

JW: Well, we didn't get paid, and no one technically won the competition; we maintain contact with the development department for the district and we know that they are building a bridge that looks similar to Zaha Hadid's entry, yet has been re-processed by a local institute. But even with all that said, yes, we would do it again... and again. We're designers. We can't help ourselves.

We don't know if any of the other participants will be paid or have been paid, but I am fairly confident that other participants in the competition are getting some form of work as result of their submission. In China, the "relationships" and the "connections" are far more important than the money. When addressing a Western audience, its fun to joke about not getting paid, the client stealing your design and giving it to a cheaper firm, and the list goes on, but anyone who actually understands what's going on, understands that it's what is not said that is most important. Everyone knows that sometimes you will benefit more greatly than just getting cash in hand, and sometimes you get screwed, but you have to understand the flow and the obscurity of the situation in order to actually benefit.

Our company is fairly unique. To foreigners, we are viewed mostly as locals, and to locals, we are viewed as foreign. We occupy a strange middle-ground because the founders here are foreign, but our company has grown up and matured in China, and therefore we're defined by our experiences here locally. We came to Beijing because we wanted to be in the cultural capital of the country. All the big design companies trying to make a buck in China will go to Hong Kong and Shanghai. Shanghai is China's corporate headquarters. So if we were here to make money from China's growing market we too would be in Shanghai.

We didn't want to perpetuate or associate with the perception of the Western company coming to China to make money and show them (locals) how things are done. We wanted to develop organically in conjunction with the country and its development. We are also driven by the arts, and Beijing is not only the political capital, but the artistic capital of China. This middle ground we occupy is the future for design in China. The reliance on Western design firms is diminishing in China. We are inserted here in the culture in a way that is positioned very differently than most foreign design firms, and I think that our patrons and clients perceive this.

-

Jacob Slevin is the CEO of DesignerPages.com and the Publisher of 3rings & Otto.