In 2013, I began writing a children's book featuring an 11-year-old girl struggling with cancer. It's a fantasy and one of the main characters, Grace, happens to be stuck in the hospital because her life has taken a detour into Cancerland. The book, Doorways to Arkomo, was heavily inspired by my love of C.S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia except instead of a wardrobe, the vessel to the strange and sometimes terrible world of Arkomo is the hospital itself.

At the time I wrote the book, I didn't know about John Green's The Fault in Our Stars (TFiOS) which had been released the previous January or the inspiration behind the main character of Hazel (her name was Esther Earl and she was remarkable.) I'll come back to TFiOS in a bit, because it's a pivotal work of fiction that has brought a unique kind of awareness not only to pediatric cancer, but, specifically, to teenagers with cancer (a group near and dear to my heart).

My intention with Doorways to Arkomo (at least at first) was to preserve the experience of the hospital and the feeling of otherness that descended on my family when my daughter got sick, ripping us out of our comfortable (and oblivious) lives. When I started writing the book, my daughter was in remission. She was two months past the liver transplant that had saved her life and had returned to school. Though she was now required to get frequent follow-up scans and take medication for the rest of her life, we were finally getting back to normal.

Yet... it was impossible for me to continue on as if nothing had happened. As I watched my daughter slowly regain her health, her weight, and find joy in the simple pleasures of childhood, I realized that I didn't want to forget everything she'd just been through (as if that was even a choice.)

People suggested I write a memoir. I'd blogged about my daughter since the first day of her diagnosis, literally writing from the cot beside the bed in her hospital room. But I'm a fiction writer and fantasy lover. My heart and soul reside somewhere in Narnia, forever delighting in the first glimpse of that magical land through the cluttered framework of an old wardrobe.

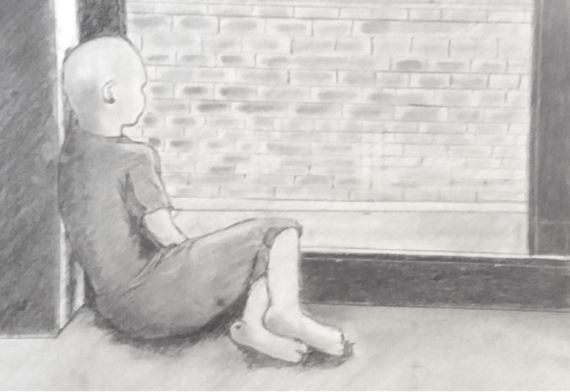

I couldn't forget the awful and surreal experience of the hospital. There's an otherworldly quality about hospitals that flips reality upside down. Immortalizing my daughter at the age of 11, stuck in the hospital -- angry and scared -- was my way of preserving that incredibly chaotic time in our lives. I chose to fictionalize the very real experience of her first six months with cancer. I named my main character Grace because it is the literal meaning of my daughter's name, and the story began to unfold.

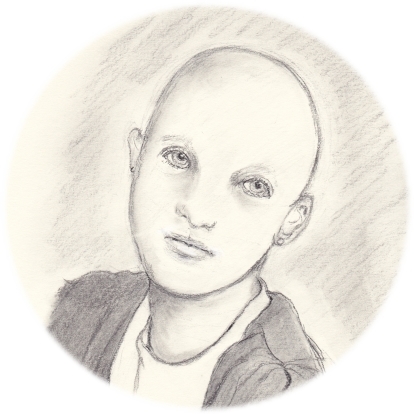

By the time I finished writing Doorways to Arkomo in late 2013, my daughter's cancer had returned. I wrote the book with the hope that someday she'd read it and finally get to see for herself how amazing she'd been -- a child thrust into an impossible situation who nevertheless persevered. But as I unwound the thread of the story, I changed the character of Grace in subtle ways so that though she was an echo of my daughter, this fictional daughter was an entirely new person.

My purpose in creating Grace began to grow from chronicling my daughter's experience with cancer to honoring other children who were going through similar things. I wanted to show them, in my way, that I saw them too. I'm still seeing them. I wanted them to see themselves cast as an epic hero in spite of their illness (and not because of it.)

As I wrapped up the book and began to prepare it for self publication, my daughter had another surgery to remove additional tumors. She began various new treatments to slow the spread of her disease which was now in her lungs.

Her doctor discovered a breakthrough drug that she could take in pill form and this drug worked (for a while) to significantly slow the progression of disease. I mention this because it's very similar to what happened with the main character of Hazel in John Green's aforementioned novel.

It was during this time that my daughter and I read The Fault in Our Stars. I honestly think I cried through the entire 300 page book. My heart ached and my cheeks were always wet. It is a beautiful tribute to Esther Earl without really being about Esther. My daughter loved it too, even though she was perpetually getting bad news about her lungs even as she read it. I'm grateful to John Green for the character of Hazel, grateful that my daughter finally got to see some of what she's going through represented in a character she loved.

Writers of children's fiction have a unique responsibility. We should absolutely be creating diverse and under-represented characters, but our motivation must be clear. If we're trying to ride a trend (e.g., cancer as tragically cool), then the character will fail to resonate with people (at best) or offend and hurt people (at worst). But if we're authentic and truly inclusive, then a character like Hazel Grace in The Fault in Our Stars or Auggie in Wonder have the potential to raise awareness about kids forced to deal with things like illness, disability and disfigurement.

The character of Grace isn't defined by her cancer. She is a child dealing with a horrible illness who must navigate the very real world of the hospital and the fantastical world of Arkomo. By the end of Doorways to Arkomo, Grace is bald. She is malnourished. She has a port in her chest and is so weak that she needs a wheelchair even while in Arkomo. Yet she still manages to save the world. This is how I want kids with cancer to see themselves.

--

All illustrations in this post were created by Judith Krongard. They were originally published in Doorways to Arkomo or Doorways Home.