I am serializing an unpublished book in this column. It's about an amazing, mysterious manuscript I discovered in Scotland. It's a little book with nothing in it but 50 watercolor paintings. No one knows who painted it, or when, or where, or what it means. I was so entranced by this that I wrote a whole book of comments and thoughts on it. I call the book What Heaven Looks Like because the person who painted this was dreaming, I think, of an ideal world, a kind of heaven.

You can read the first installment here, if you want to: but if you're coming in late, no problem. No one knows what this book is about, so you can suggest your own ideas, and we can build a collaborative interpretation. (The first post got some great comments! Thanks so much everyone!)

This time I'm posting 5 pictures at once, because they go together. Some of the other plates in the book are so weird that I'll post just one or two at a time.

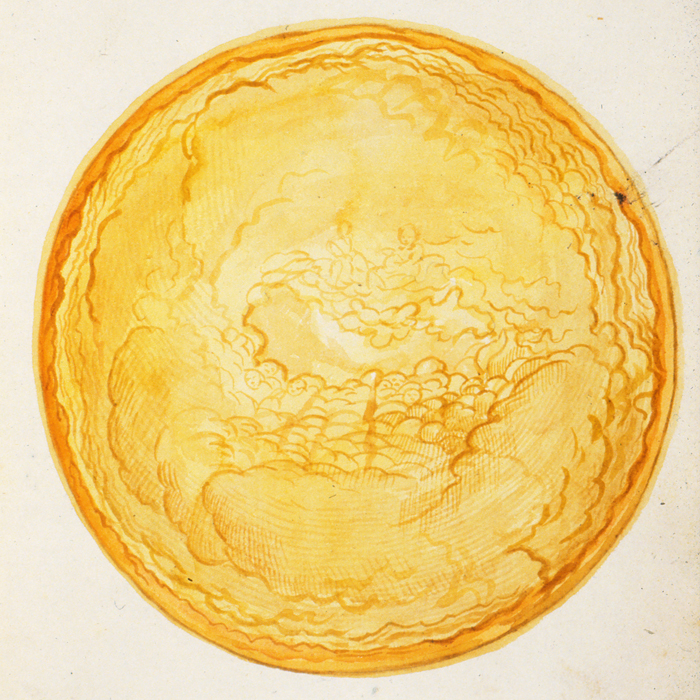

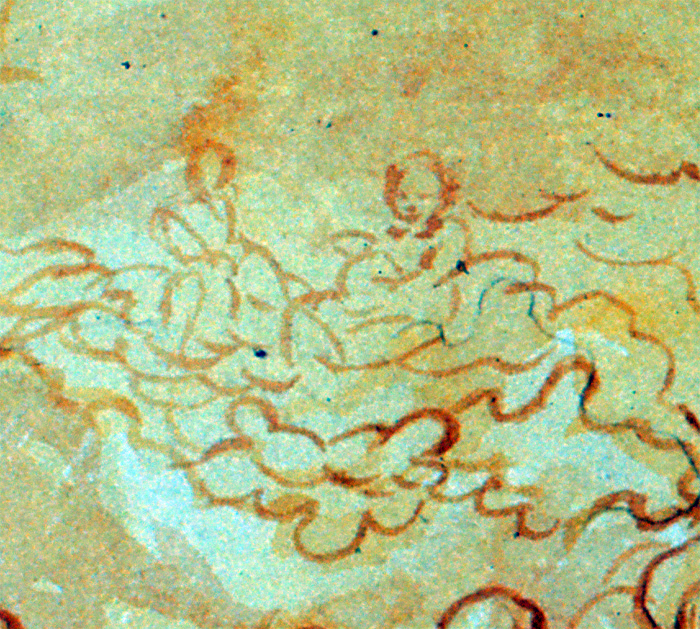

Plate 2

With the second picture we have at least the beginning of a narrative. This is clearly heaven, with two figures reigning in the sky. To any Baroque beholder they would have been God and Jesus. The clouds just below the center are infused with little heads: again something a viewer would have recognized, because painters of the time populated their heavens with little bodiless angels. (They could also be the unstained souls of the unborn.)

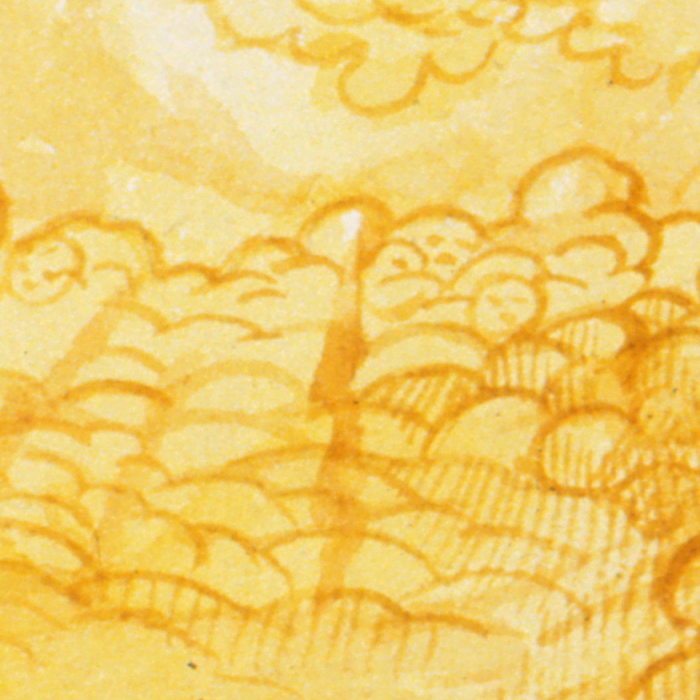

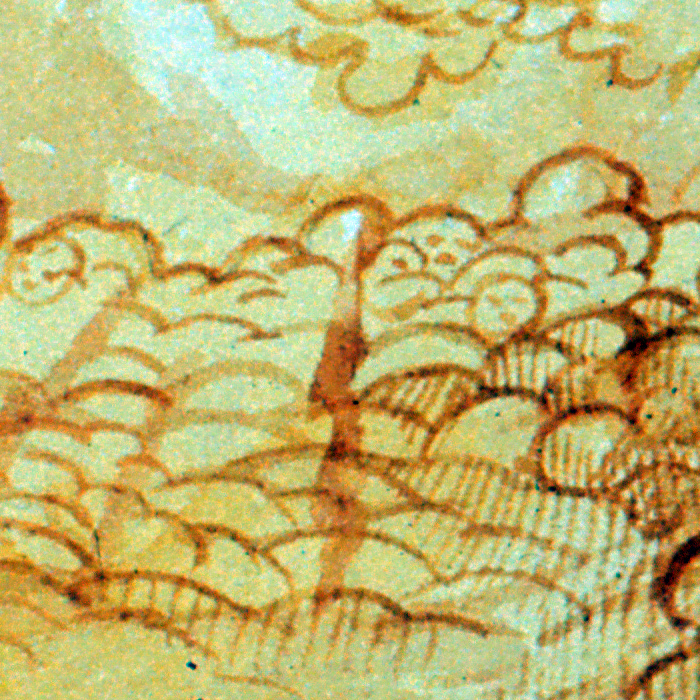

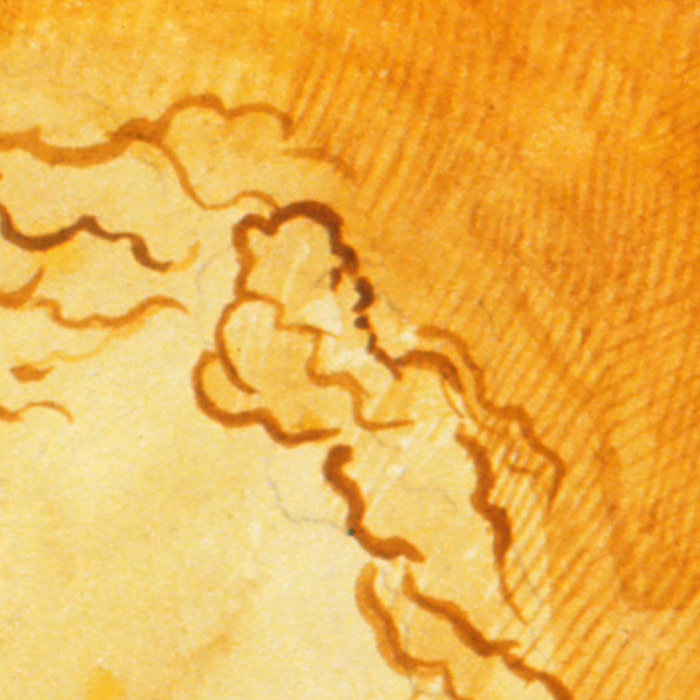

Here's a detail of the little angelic heads:

And here's the same detail, enhanced in Photoshop:

(I'll be posting some Photoshop-enhanced images as we go along. I won't do this often, because I think it's important to experience the book as much as possible the way it was originally intended to be seen. The full images, if they're seen on an average computer screen, are more or less natural size. So I think it's important to be careful not to enlarge things too much--you start seeing things that the original viewers wouldn't have seen, and you start thinking the artist was hiding things--but still, in this case, the painting is so faint that it helps to see it a little more starkly.)

At this point it looks like this book may turn out to be a story about heaven and earth, or perhaps a journey from earth into heaven. A viewer at the time might well have been comforted by that fact, since it was conventional to depict the creation of the world in a series of round paintings. The first painting could be the creation of the earth, and this second a picture of God in heaven, resting after the creation. It is not exactly what a viewer might have expected (it would be more normal to show the seven days of the creation, one after another) but close enough to look like a familiar story. Domed church ceilings were painted as apparitions of the heavens, glowing in golden light and banked by clouds, and there were especially famous examples by Correggio that resemble the brightness of this painting.

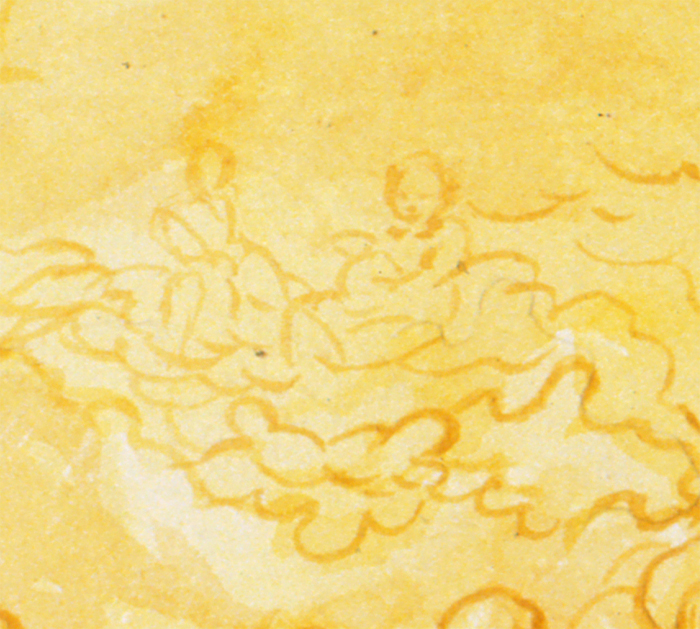

Here's a detail of the center of the painting:

And here's an enhanced version of this detail:

Still, something is not quite right about this heaven. Never before had heaven been quite this indistinct. The only way we know which figure is Jesus is that he sits to God's right. They have no faces, no hands, and no thrones; they are blurry and distant, like mirages. There is no real sunburst, no heavenly blue. Instead everything is bathed in a sweet midsummer haze, as if the artist were slightly dazzled.

The scene is close to a normal one, but it is unsettling. What is God if he is only a faint orange silhouette in the distance?

Plate 3

In the third scene, something is definitely wrong. The sky is whirling, and the angels are gone. God--if that is who he is--holds a bolt of lightning, and other lightning-bolts strike all around. On one side a cloud bank rears up like a wave, and on the other a small tempest is pouring rain.

When god holds a thunderbolt, he is probably Zeus, and there's a feeling here that we have passed out of the Christian world and into the pagan. But who is the other figure? Zeus reigned alone, or with his wife. The second figure is a surly young man, possibly naked. He almost looks suspicious.

This is the kind of puzzle that delights art historians. It isn't God the Father and Jesus, because God doesn't throw lightning. And it isn't Zeus (even though he has Zeus's tousled hair), because Zeus didn't share his throne with a naked man. In other artworks there is usually a solution: either the painting is Christian, or it's not, or it's some comprehensible mixture of the two. In the eighteenth century there are paintings of God, and paintings of the gods, but there are no paintings that might be God or the gods, or paintings in which heaven can be occupied by just anyone.

The artist is in a rare frame of mind: she allows her imagination such free rein that it wanders against the rules. First it brought her a hazy, enervated heaven, occupied by a distant Father and Son, and now it's brought her a strange, possibly heretical heaven, occupied by two vaguely divine men.

The lightning bolts, of course, are radial cracks in the wood. It was customary to paint lightning as straight lines (or as zigzags), and so these lines would have looked like lightning to the artist. But what an interesting decision, to look only at the cracks and hallucinate everything else.

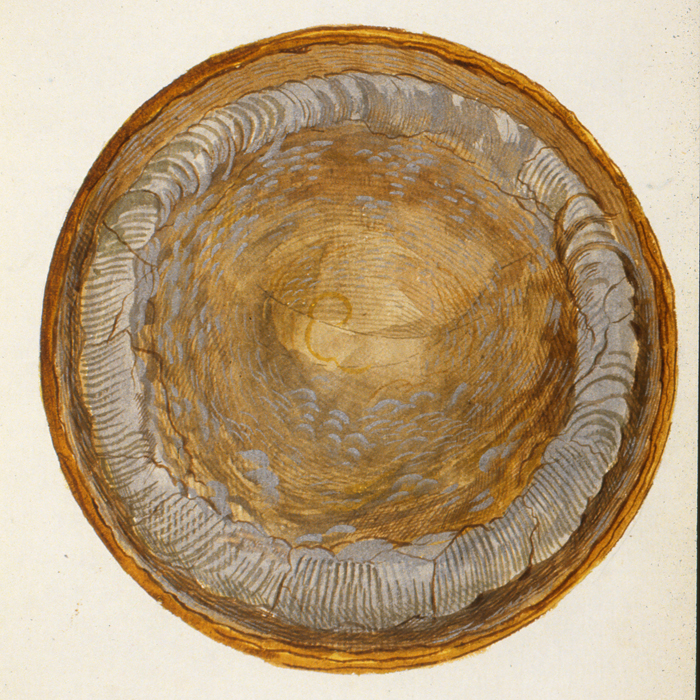

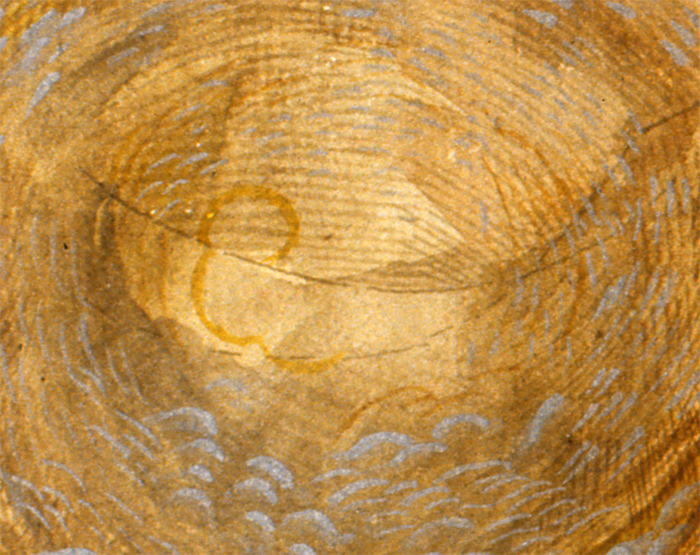

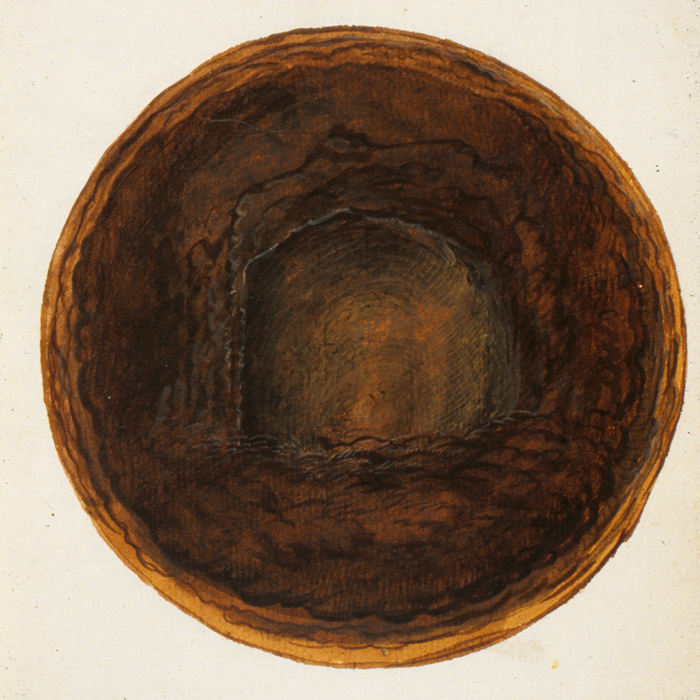

Plate 4

And now comes the pièce de résistance, the seal of strangeness.

At first it looks empty, as if all the divine and semi-divine figures have left. Heaven is overcast, and a silvery ring of thickened clouds frames a diminished golden center. The sky is crisscrossed with parallel hatching, which meant rain before and may mean it again here. A curved line--an echo of the lightning bolts in the previous painting--lies across the exact center, and above it the sky is shaded.

But this is more than a deserted heaven (if it were, it would complement the deserted earth we saw initially). Very faintly but definitely, there are still two figures. In reproduction they are especially hard to make out, but on the original there is no doubt.

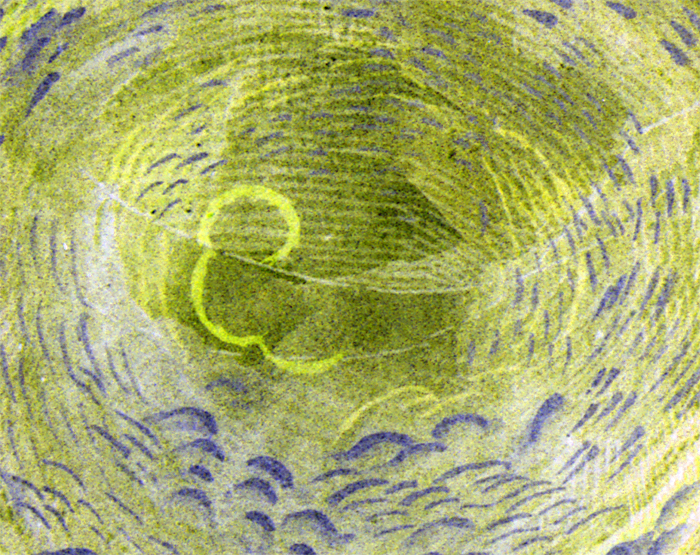

They are both outlines, painted in a pale olive green different from any other color in the plate. The left-hand form is large and round, and just left of the center. His head--if that is what it is--trails off to the right, crossing the midline of the plate, and then arcs upward and slightly left, forming the outline of a second figure. The companion is tall and gaunt, and leans over toward his friend. They both have heads, but nothing inside, and their bodies trail and merge. In the shadows at their left, there are other wisps of figures--too faint to count, or clearly see.

I tried, in Photoshop, to bring out just the outlines of the two figures, but their color is too close to the color of the surrounding lines. (Maybe someone can do a better job. In the original, their slight difference is clear.)

There is nothing even remotely like this until the twentieth century. (Kandinsky simplified figures in a similar fashion in the 1910's.) It is an amazing, almost inconceivable act of imagination to think of painting such distorted and schematic figures, and letting them stand alone without explanation.

Thinking over these first paintings, a viewer might well decide the artist felt alone in the world. Gods seem to mutate into one another, or evaporate altogether, and so far there are no people at all. Centuries earlier, Epicurus had thought along these lines: gods, he said, are paper-thin and can do no one any good or harm. People should be kept at a distance because they cause pain.

Plate 5

Then we turn away from heaven, and look instead at a blank wall.

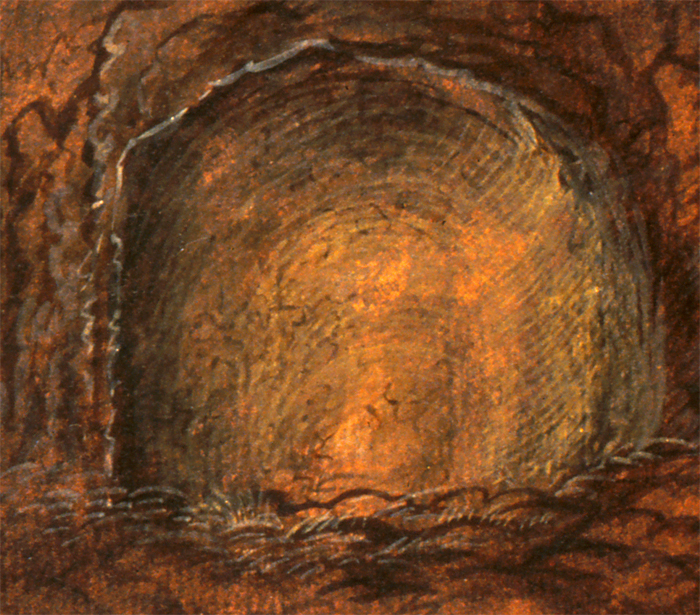

It is very dark, and I find myself peering close to the page. Perhaps this is the back wall of a cave, or a darkened place shadowed by trees. If it's a cave, it may be the same one we looked out of at the beginning.

Yet it isn't just a wall, it's a niche: a scalloped depression meant to showcase a sculpture. A Baroque viewer would have seen the painting as an incomplete image. It needs a statue: perhaps a bronze fawn with his mouth spouting water, or a little marble Hermes or Priapus. But there is nothing.

Here's a brightened and contrast-enhanced detail. (I do think the niche is empty: maybe the enhanced contrast is misleading here, because when I look at it I start to see things. In the original, everything is dark, and you peer and peer and see nothing.)

Fanciful gardens were very popular in the period; some had artificial grottos, and dusky places hidden in woods. People liked to think about deep antiquity, and they made dilapidated temples, little churches overgrown with ivy, and strange sculptures of pagan gods. But they did not make niches and then leave them empty. Baroque gardens were whimsical and romantic; this is bleak.

After a few minutes looking into the darkness, one becomes aware of an enchanting play of light. The rim of the niche is silver blue, and the niche itself shines faintly with a rainbow of colors. On the original (such subtle colors do not reproduce well) the center is a warm peach color, and around it is a halo of pale green, with the light tint of a freshly broken sapling.

The colors are reflected from a light source that is somewhere behind us. I assume it is meant to be the setting sun, and that the blue is an echo of the azure sky. If we are in a woods, it is that time a few minutes after sunset when it becomes difficult to see, and the trees around merge into blackness. Or, if we are in the back of a cave, it might be broad daylight outside, and these are the few rays that have penetrated into the last chamber.

This is a sad image, as forlorn as the artist gets. It almost seems to say: There are no people on earth, no gods in heaven, not even any sculpted images that might give us solace.

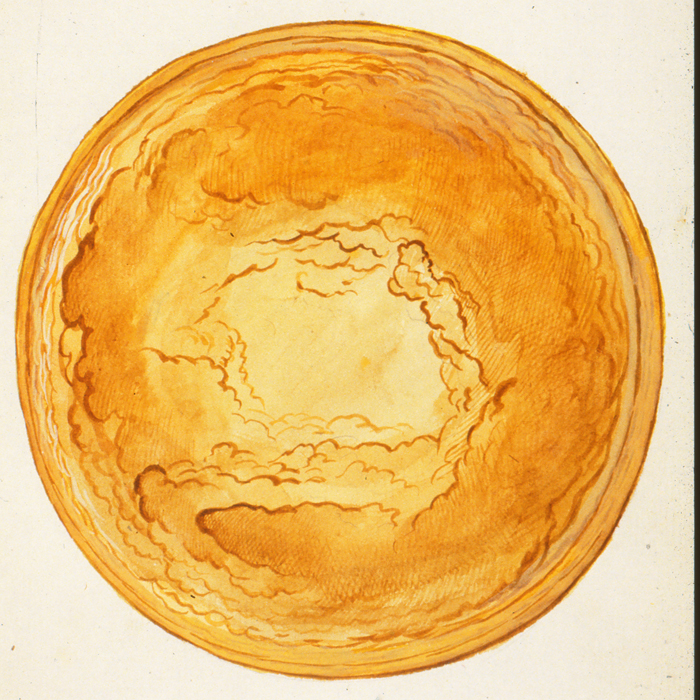

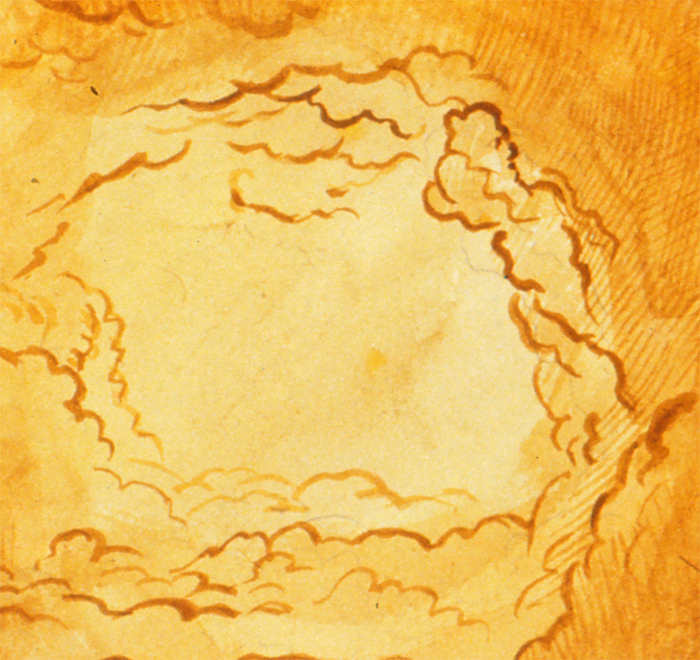

Plate 6

Just at that moment, the artist shows a strength that is uncommon in the history of Western art before modernism: a sense of humor. We look back up to heaven--as you might expect, after peering into the failing light--and find--as you might expect--that it is empty.

Or almost empty: there is a face here, this time not the ominous empty outline of a spectral figure, but a comical face, a kind of joke. You can spot it just to the upper right of the central opening, facing away from the light. It is a man, with a broad Roman nose and pinched lips. If he had a torso, it has evaporated. He is so much a part of his cloudy surrounding, in fact, that it doesn't even seem bothersome when two more clouds grow out of his shoulder as if they were about to become extra heads.

When things are this subtle and this unexpected, it may look as though I am hallucinating or projecting my own fantasies into the pictures. Maybe there is no face here, you might say, or a hundred faces. But there is unequivocally a face in this painting, and only one face. It is painted with the darkest pigment in the picture, so that the eye eventually finds its way there; and it is quite explicit, with its inset chin, pursed lips, high forehead and coiffure. People who see it tend to set off on hunts for other figures: one person saw a ghostly dog in the glowing center of the niche (in the previous painting), and I once thought the little grey bumps in the fourth painting might be echoes of angels' heads, in attendance on the ghostly pair. This artist is playing with seeing things, and she sees in the most extraordinary ways: but her game is not endless hallucination. I think she wants us to think about seeing things, and she wants us to wonder if we are seeing things. But she can also be very exact about actually placing figures.

This is a painting with a single, entirely surprising and inexplicable figure. He looks like an ordinary person--perhaps even the artist--who has wandered into heaven by mistake. It is empty, and so he is leaving.

That seems to be the end of the first story about heaven and earth. The next plate starts something new: landscapes where interesting events are unfolding.

I'd love to hear everyone's thoughts about this very unusual heaven.