The woman saw me before I saw her. As I got out of my parked car and slung my purse over my shoulder, she walked briskly up to me. "I just want to give you the biggest hug," she said, enveloping me in an embrace that was much too tight and lasted far too long.

The thing was, I barely knew her. I couldn't even remember her name.

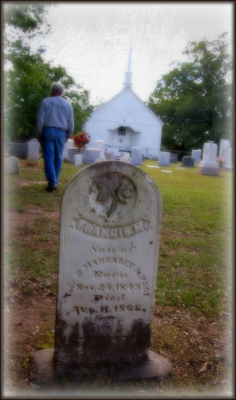

Two months earlier, my husband and I had lost our son, our only child, in a car accident.

We had been buoyed, even overwhelmed, by the outpouring of love we'd received from friends and colleagues in our small town on the North Carolina Outer Banks. We couldn't have asked for more.

But we were also stunned by the many times that people did or said something entirely inappropriate:

The neighbor who told us we could borrow his 9-year-old son whenever we felt lonesome for our own son.

The friend who told me she knew her pain didn't equal mine -- but that when her son had been injured and lost his chance to play football in college, a part of her had died.

The county official who, while waiting for a sandwich at Subway, saw me and quickly turned his back so he could pretend he hadn't.

These people weren't daft, just flustered. They had no idea what to say to a mother who had experienced the unspeakable.

When it comes to grief or misfortune, Americans can be stunningly ungraceful at showing each other tenderness. We live in a society where much of the time suffering is kept hidden. To some degree, it's also considered shameful. No matter what happens, we're expected to maintain our composure and soldier on.

This has clear emotional costs to people suffering through loss. But its toll is just as real for those of us with bereaved friends and family members. We long to comfort them but often don't know how.

Yet some people instinctively do know. The two women with whom I worked seemed to have a knack for sensing when to talk and joke with me and when to leave me alone. They didn't have any special talents. They were just more attentive and perhaps kinder than others.

In brief encounters, the most helpful response was a simple gesture of acknowledgment and compassion -- nothing fancy, just, "I'm so sorry about your son," and perhaps, "I'm thinking of you."

Don't be uncomfortable if this is followed by a few moments of silence. It can give both parties a chance to reflect on the pain of loss. It also allows the bereaved person an opening to say something, perhaps even share a memory.

My husband and I were put off by that standard condolence of our times: "I'm sorry for your loss." We heard it so often and uttered with so little emotion that I began to associate it with my misplaced car keys.

Much better were the simple phrases that mentioned our son personally and were said with feeling:

"He always dragged that stuffed dog around when he was little."

"I didn't know him, but I remember when you were pregnant. You seemed so happy!"

Or simply, "I'm really sorry. It must really be hard."

A few friends tearfully asked if we were going to be okay. These were odd exchanges, and as unexpected as the bear hug from the unknown woman. The implication was that they couldn't be okay unless we were. I found myself putting on a brave front, assuring them that I was fine, when I was anything but.

Worst of all were the people who remained silent about the accident. I suppose they thought it would be kinder not to remind us of our son's death. But that was all we could think about. So when a friend or acquaintance failed to mention it, it seemed like a slap in the face.

The social behavior researcher Brené Brown writes that to be fully human, we must be willing to show our vulnerable side to others. The best way to do that with a bereaved friend is to admit the obvious: "I hurt for you. I wish I could fix this for you, but I can't." There are countless ways to convey this, including sitting with the person in silence. Saying only a few words is often the best option.

People handle grief in different ways. I know the things I found helpful might not work for others.

Still, the safest, most surefire strategy is to approach the bereaved with a quiet presence, taking your cues from them. If they want to talk about their loved one, let them. If they turn the conversation to you and your losses, that's fine too.

And if, in the end, they feel comfortable sharing a bear hug with you, have at it.