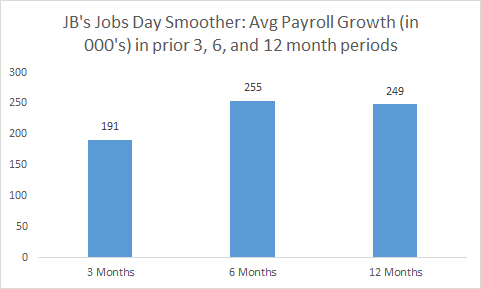

Payrolls rose 223,000 last month, in line with expectations, and the jobless rate ticked down to 5.4%, a seven-year low. March's already low payroll gain was revised down to only 85,000; combining that with February's revision takes payrolls down 39,000 over those months. As shown below, the March outlier takes the three-month average down to about 190,000 jobs per month over the past three months, a slower trend of payroll gains then prevailed last year.

The jobless rate ticked down slightly, and for the "right" reasons: more jobs vs. fewer people in the labor force. The closely watched (i.e., by labor market nerds and Fed watchers) labor force participation rate ticked up a tenth to 62.8%. At this point, it's fair to conclude that the lfpr has stabilized at around 63%, where it's sat for well over a year now.

That's better than a declining rate -- at least some of the decline was driven by labor-force leavers discouraged by their job prospects. But most analysts, myself included, believe there's considerably room for the lfpr to tick up as labor demand returns. The reason this matters -- why it's actually a big deal -- is that this dynamic means there's more slack in the job market than the relatively low unemployment rate suggests.

By smoothing out the jumpiness in the monthly data, JB's Jobs Day Smoother shows 3, 6, and 12-month averages of monthly payroll gains. This month's smoother is suggestive of another important development in the job market: the slowing of monthly job gains, from an average of around 250,000 to around 200,000.

Source: BLS, my calculations.

While we'll need more data to accurately assess this deceleration -- three months, party driven by an outlier low for March, is not dispositive -- there are reasons why this slight downshift could stick.

First, the strong dollar appears to taking a toll on manufacturing employment, as can also be seen in the rising trade deficit in manufactured goods. Recall that when the value of the dollar rises relative to the currencies of our trading partners, our exports are more expensive to them and their imports are cheaper here in the malls of America.

Over the past three months, manufacturing employment has been essentially flat, compared to average gains of 27,000 per month over the prior three months. Again, this new trend bears watching to see if it sticks, but if so, it will constitute a headwind on both growth and jobs.

That said, manufacturing employment is now only 9% of total employment, so as long as service employment continues to grow, we should expect to continue seeing gains in the range of those in today's report.

Other factors that could contribute to future payroll gains that look more like the first bar in the figure above include slower GDP growth, underwhelming investment, job losses in energy extraction as oil prices remain low, and planned tightening by the Federal Reserve. While the Fed has yet to raise rates to slow the economy -- in large part due to remaining job market slack and some of headwinds noted above -- their "body language" is certainly leaning in that direction.

Both hourly and weekly earnings were up 2.2% over the past year -- weekly hours worked were unchanged -- which is about where they've been for years. Taking averages of hourly wage growth over recent three-month periods, there's slight evidence of acceleration: annualized hourly wage growth over the past three months is up 2.3% compared to readings of about 2% in prior three-month periods. That's certainly what we'd expect to see as the job market tightens up a bit but it is not enough to confirm a lasting break in the persistently flat trend of wage growth.

Other positive indicators in the report include a slight decline in the number of involuntary part-time workers -- that important measure of slack is down almost 900,000 over the past year -- and a continued decline in the share of the unemployed who are long-termers (out of work for at least six months). At 29%, it's far off of its peak of around 45% five years ago.

Stay tuned...more to come...

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.